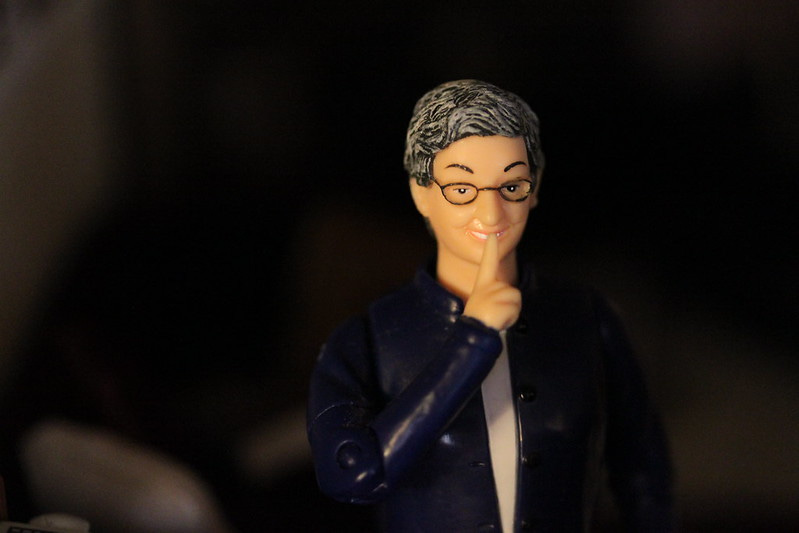

Library Twitter's Push-Button Shushing Action

Nancy Pearl and Me: Reflections on the Changing Ethos of American Librarianship. Part 2 in a series by John Wenzler for Freedom to Read Week.

John Wenzler, guest contributor.

“We were creating a world where the smartest way to survive is to be bland.”

―Jon Ronson

The Twitter Pile-On

I never would have learned what Pearl said at the 2022 ALA if I wasn’t addicted to reading Twitter.

I did not attend the convention. I was 3,000 miles away in California at the time and not paying much attention to it. The first Tweet about Pearl’s comment was posted at 2:30 pm on June 25, 2022 by Kelsey Bogan, a librarian who attended the United Against Book Bans panel discussion. Bogan hosts a website called “Don’t Shush Me! Adventures of a High School Librarian.”1 She has presented frequently at library conferences and is a strong proponent of the pro-social morality school of library thought. She has advised librarians to be careful about sharing problematic or harmful authors such as Shakespeare, Dr. Suess, J.K. Rowling, and Sherman Alexie with young readers.2 It is not surprising that she was shocked by Pearl’s claim that we shouldn’t ban Holocaust deniers from libraries, let alone Shakespeare or Dr. Suess.

After leaving the session, without sharing her concerns directly with Pearl or any other of the panelists, Bogan Tweeted:

At an ALA session about “Uniting Against book Bans” today there was a sentiment made by panelists that we even must include Holocaust denial books. Holocaust denial is harmful misinformation. I’m urging @UABookBans @Nancy_Pearl @JasonReynolds83 to please reconsider this stance.3

Bogan’s Tweet generated a significant amount of engagement for a library conference post. Compared to official #ALAAC22 Tweets that usually generated around 30-60 likes, Bogan’s Tweet was liked 786 times, reposted 222 times, and frequently referred to by librarians talking about Pearl, both-siderism, and library neutrality.

I am not an expert in social media engagement, but Bogan’s Tweet and the Twitter discussion about Pearl became the biggest online event of the conference, and it seemed like everyone was talking about it. A colleague from the California State University (CSU) system chastised Pearl for not knowing better.4 An author, who was a classmate during my undergrad days at Berkeley, lectured Pearl on the political error that she had “stumbled” into.5

As I remember the Pearl pile-on that I followed with fascination and dismay, four things strike me as important. I’ll try to explain them below.

When the mob went after Pearl, they went after me—and any other librarians who still agreed with us (if there were any more of us left).

First, Pearl’s comments quickly became a thought-crime rather than a legitimate intellectual opinion that good, upstanding people might entertain. Thought crimes shouldn’t be discussed and debated but punished and suppressed, and thought criminals need to be ostracized from the moral community until they have been reformed.

The content of Bogan’s initial Tweet is ambiguous on this point. Her request that Pearl “reconsider” could be seen as the opening move in an intellectual debate, but the medium is part of the message here. Bogan failed to address Pearl directly before broadcasting her concerns to the world. And her short 38-word post assumes rather than argues that Pearl is morally wrong. The primary purpose of the Tweet was to expose Pearl’s unforgivable opinion to everyone else rather than to engage with Pearl to discuss their differences.

Most of those who responded to Bogan’s Tweet certainly assumed that she had exposed a thought crime. The condemnation of Pearl was almost universal. There was no other side to consider on Twitter. The issue was not difficult and challenging as Pearl had asserted but simple and morally obvious. After reading the 38 words in Bogan’s Tweet, without hearing or reading what Pearl had actually said, most responders on Twitter knew that Pearl had done something inexcusable. Almost no one was crazy enough or brave enough to publicly defend Pearl or support her claims.

As the evidence of Pearl’s perfidy got diffused through library Twitter, the anger against her mounted, and the rhetoric became more intense. For example:

“There are books w/historical facts. And then there are books w/the lies of white supremacists, racists & bigots who want to radicalize others with those LIES & their hatred. Only one of those should be on library shelves.”6

Or

“Like for a regular library's collection they said that? Unless you have a legit research need for that garbage, you absolutely don't need to consider that topic at all. That is jacked af.”7

In the Twitter discourse, refusing to censor Nazis became essentially equivalent to endorsing them. Although Pearl, who is Jewish, had described her own disgust with Holocaust denialism when making her point, she might has well have shown up at the convention wearing a brown shirt with a swastika armband based on the Twitter response.

Second, Pearl’s seniority, her accomplishments, and her fame as “America’s Librarian” made things worse rather than better for her. Provoking students is often a good teaching strategy. If a respected authority tells you something that you intuitively believe is wrong, it can stimulate your thinking. You think to yourself: “She usually knows what she is talking about, I wonder why she would say something so crazy?”

Regardless of whether the student ultimately decides to agree with the teacher, the provocation challenges them to examine their intuitions and understand them better. Pearl had been a successful librarian for 40 years, had won awards for her service to the profession, and had been a respected teacher of new librarians for many years at the University of Washington. Perhaps her scandalous assertions could have generated interesting reflection in those who were shocked.

Instead, Pearl’s fame only increased the sense that she had betrayed the profession. As with her decision to partner with Amazon in 2012, Pearl’s apparent willingness to associate with moral evil threatened to soil the entire profession with unsavory connections due to her notoriety. The fact that such a famous librarian had advocated “both-siderism” was distressing for many. One librarian complained:

“I went to #alaac22 for two days and brought home COVID, [and] a ‘both sides’ argument from a prominent white woman in the field.”8

Pearl’s beliefs were repeatedly dismissed as outdated on Twitter, and her outdated ideas had not simply been surpassed but exposed as actively evil. Her willingness to tolerate Holocaust denial proved that her old-fashioned assumptions of library neutrality were tied to fundamental American sins of white supremacy and racism.

Third, Pearl’s Twitter shame metastasized and spread to others around her. Bogan complained that the ALA had “platformed” Pearl, essentially accusing the ALA of committing a third-level thought crime. Holocaust deniers committed the original crime. Pearl committed the second-level crime by refusing to censor them, and the ALA committed the third-level crime by refusing to censor Pearl.

Pearl’s crime also spread to Jason Reynolds, a children’s author who participated in the United Against Book Bans panel with her. At the start of the pile on at least, Reynolds stood accused on Twitter of failing to make a citizen’s arrest after witnessing Pearl’s thought crime.

Because the Twitter discourse about Reynolds evolved in interesting ways that were only tangentially related to what he actually said at the convention, I’ll quote his relevant comments here in full. I take them from a transcript in a School Library Journal article published on July 1, 2022 after the Twitter blowup had occurred. Most of those who were opining about him on Twitter had not heard or read what he actually said. In referring back to Pearl’s Holocaust denial comments, which had come earlier in the panel discussion, Reynolds said:

Like when you said that it kind of hit me in the gut like ‘Ooof,’ when we were talking about people who are Holocaust deniers, right? And books written by Holocaust deniers. And you know immediately my knee-jerk reaction is like, ‘That feels dangerous.’ But the truth is, the hard truth is, that if we are going to fight against book bans, it includes all the books, and I think that's what makes it a complicated gig, but that's also what makes it a necessary thing.9

In the live face-to-face discussion at the conference, Pearl’s provocation seemed to have had the intended pedagogical effect on Reynolds and convinced him to agree with her assertion. It was only later, when he and Pearl were getting yelled at on Twitter, that Reynolds clarified his position and explained that he really didn’t mean to include Holocaust denial books when he said that fighting against book bans should include “all the books.”10

Although Reynolds was initially attacked by same Twitter mob that went after Pearl, the mood turned eventually, and he was seen as more of an innocent bystander caught in the crossfire. The change had less to do with what he actually had said than with his identity as a Black children’s author. When librarians on Twitter figured that out, Reynolds was reevaluated with a sense of generosity (towards his moral character if not towards his intelligence) that few offered to Pearl. Whereas Pearl’s comments revealed the underlying white supremacy of traditional librarians like herself, Reynolds was a well-meaning dude if confused and disoriented by Pearl.

As one blogger explained the Library Twitter zeitgeist:

The poor man had no idea what was going on, nor what he was ‘agreeing’ to. Most normal people don't understand that there are librarians who actively defend Holocaust Deniers. Why would they? It is horrendous. I am sure he was utterly confused. If nothing else, his mangled response should make us see how dire it is for us to make a stand.11

Ultimately, Pearl (and her old-fashioned library values such as neutrality and non-partisanship) were the active agents of evil while Reynolds was a mere passive victim duped by the horrendous beliefs of librarians like Pearl.

By June 30th, five days after her initial Tweet, the shift in the public attitude toward Reynolds convinced Bogan that she needed to apologize to him. Her apology is intriguing on several levels. She acknowledges the “harm” that her original Tweet had caused because it “led to Jason Reynolds being focused on & targeted.” Of course, if Reynolds was targeted, Pearl was too and more so. The primary difference was that no one stood up to defend Pearl’s character as they did for Reynolds.

But Bogan saw no need to apologize to Pearl because Pearl apparently deserved what she got. In fact, the harm unfairly suffered by Reynolds only redounded to the further detriment of Pearl’s character. Pearl ultimately was responsible for Reynolds’ suffering because she had put him “in a bad spot.” Although Bogan had erred by including Reynolds in her exposé of Pearl, she never would have made that mistake if Pearl hadn’t committed the original thought crime in their presence.12

The fourth thing that I noticed about the Twitter pile-on is that I was ostracized along with Pearl.

I was 3,000 miles away, and no one knew that I was paying attention, but, when the mob went after Pearl, they went after me—and any other librarians who still agreed with us (if there were any more of us left). Watching librarians go on Twitter and say that anyone who agreed with me were “horrendous”” or “jacked af” made me wonder if my presence was still acceptable in polite librarian society.

I completely understood why Pearl and Reynolds immediately wanted to disavow what they had said at the convention to get back in the good graces of their colleagues. But I didn’t want to do that. I still believe what I believe and think what I think. Would I ever be able to go to an ALA conference again and express my true opinions without becoming a moral outcast in the eyes of most of my colleagues? I easily could escape ostracism by staying silent, but not as someone who enjoys the intellectual freedom that the ALA supposedly celebrates.

I also doubted myself. I’ve never been able to believe in my moral opinions with the self-righteous fervor that many displayed on Twitter. They were so confident in their virtue, and they all agreed with each other. Didn’t I have to reconsider my own opinion and ask myself why it seemed to be so universally despised by so many of my colleagues? But there was nothing I could really do to resolve my doubts. Librarian Twitter didn’t want to discuss the difficult challenges of censorship and library neutrality with me. It didn’t want to explore and negotiate the ambiguities and contradictions. It just wanted me to drown my thought sins in the privacy of my heart and try to think better thoughts in the future. At least, that’s the way that I felt when I was reading Twitter in 2022.

Lastly, of course—and I’ve avoided saying it until now because it is hard to say—2022 Librarian Twitter made me a coward.

Pearl’s critics bullied her into abandoning core professional values.

It never occurred to me to respond to Pearl’s critics back then. In part, this was due to a long-standing policy of staying out of the Twitter fray. Even when there was a little Twitter thing in 2019 that involved direct criticism of me, I stayed out of it—I think appropriately in that case.

But when I was watching someone else getting dragged unfairly for an opinion that I cared about and had thought about a lot, I see now that I had a moral obligation to say something, at least to let Pearl know that there was someone else who was on her side.

I assume that it wouldn’t have made much of difference to the world. In my research on this, I did find three tweets that expressed support for Pearl at the time. None of them got any engagement or likes. And Pearl doesn’t know me from Adam. So, I don’t know if my support would have meant anything to her, but I should have expressed it all the same.

Pearl’s Response

In 2002, when 39 humorless librarians wrote nasty letters to Pearl complaining about the Library Action Figure, Pearl blithely dismissed them with a joke. In 2022, when hundreds of humorless librarians attacked her publicly on Twitter for opposing the censorship of Holocaust denial literature, Pearl decided that they were right.

I can’t criticize Pearl for that. Who knows what I would have done in her place? I’ve already acknowledged my cowardice as an observer. Furthermore, I admire Pearl’s ability to empathize with her critics. Heterodox thinkers often say that it’s pointless to apologize to a mob that’s trying to cancel you because they don’t want to forgive you; they just want to punish and humiliate you. But, in Pearl’s case, her concession calmed the storm, largely, I think, because she was so effective at articulating the world view of her critics.

Nevertheless, while I admire Pearl’s insight, I have to reject the intellectual terms of her concession. She says that her critics educated her about a new and dangerous information environment that compels librarians to alter our traditional views, but I think instead that her critics bullied her into abandoning core professional values.

I will quote Pearl’s statement at length so that I can try to explain my complex response to it. Pearl starts by acknowledging that she had included Holocaust denial literature in the collection when she worked at the Tulsa Public Library in the 1980s, and had recently defended the appropriateness of doing so in a 2017 Tulsa World article before repeating this opinion at the 2022 convention. Then, she explains:

The statements I made as a panel member and in the Tulsa World reflected how long ago I went to library school and how long it’s been since I worked in collection development. I got my M.L.S from the University of Michigan in 1967, where I was taught that libraries were value neutral and should include all viewpoints in their collections. My only job doing collection development was at the Tulsa Public Library system, where I was the head of collection development from 1988 until 1993.

But times change and libraries and librarians live in a very different world today, something I didn’t really have to consider until the ALA panel; the view that I expressed on the ALA panel and in the Tulsa World article reflected the “value inclusive, i.e. include all viewpoints” ethic that I learned in library school. Were I involved in collection development today, I would make different decisions.

There is obviously a tension between the “value inclusive/include all viewpoints” ethic and the “dangers of misinformation” ethic, and the changing views within the library profession now appropriately reflect our changing information environment. Back in the day, before Google (1998), Facebook (2004), and Twitter (2006), there was a consensual view about what was true and what was false that was agreed to by all but the furthest fringes of the population. We might be divided about who should win an election, but we were never divided about who had won an election. The problem of misinformation seemed relatively small: A library patron who read a book promoting Holocaust denial could go to an encyclopedia for further information, or to a librarian for suggestions of additional reading, both of which actions would probably have resulted in a correction to the misinformation of Holocaust denial.

Today, they would go to Facebook to be led by its algorithm down a rabbit hole of further misinformation and contact with other Holocaust deniers. At that time, the problem of suppression of unpopular viewpoints seemed large (see McCarthyism). Thus, the ethic emphasizing the dangers of viewpoint suppression over the dangers of misinformation as I was taught in library school. But, as our information environment has changed, so too does the ethic informing collection development need to change. Google, Facebook, and Twitter have clearly heightened the danger of misinformation.13

I will make four observations about Pearl’s statement.

First, it is misleading about when her views became outdated. While it’s true that Pearl had not been a student in library school since 1967, she had been teaching in library school as recently as 2011. When Pearl won the Librarian of the Year Award in 2011, Joseph Janes, the chair of the MLIS program at the University of Washington, told Library Journal that he was

“thrilled to have Pearl as a regular instructor. ‘[She wins] enthusiastic students and praise every time she teaches. … She has also agreed to join our MLIS program advisory board and admissions committee. In each of those venues, she is a passionate and diligent advocate for old and important library ideas: literacy, reading, entertainment, enjoyment.”14

It hardly sounds like Pearl was living under a rock before 2011, out of touch with new librarians and what they were being taught in school. If her ideas about librarianship became outdated, it didn’t happen between 1967 and 2011. Google, Facebook, and Twitter had been around for many years by 2011 but apparently had yet to affect the ethics of librarianship. Moreover, although the Tulsa World is an obscure paper, it is interesting that—even in 2017—Pearl could express the same ideas that got her in so much trouble in 2022 without anyone noticing or caring.

Second, Pearl is correct to focus on misinformation as the primary explanation that librarians now give for abandoning the uninhibited embrace of intellectual freedom that was more popular in the 20th century.

At the same 2022 conference in which the ALA launched its Unite Against Book Bans campaign, Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress, gave a speech focused on the role of libraries and librarians in the “misinformation age.” Pearl also is correct to tie increasing fear of misinformation to changing technology and the rise of Internet behemoths like Google, Facebook, and Twitter. There is a widespread belief, not just in libraries, but in literary, intellectual, and journalistic culture that misinformation spreads faster than it did before and is more pernicious in the digital era.

There also is a belief that the “misinformation age” has undermined a “consensual view about what was true and what was false.” The dangers of misinformation have convinced many that outdated ideas about free speech and the marketplace of ideas just don’t work anymore.15

While I believe that Pearl accurately describes the misinformation zeitgeist that generated the anger that descended on her on Twitter, I reject the intellectual assumptions of that zeitgeist. The questions of disinformation and misinformation have been intensely debated in the popular press and in academic literature since Donald Trump’s election and the Brexit vote in 2016. Many agree with Pearl’s assertion that misinformation has become a serious threat to democracy in the 21st century as digital communication has undermined the authority of intellectual gatekeepers and allowed post-truth populists to gain power by convincing many citizens to believe in conspiracy theories that undermine liberal democratic values and the scientific method.

But there also has been a strong counterargument to this thesis, which asserts that danger and significance of 21st century misinformation has been greatly exaggerated, especially when compared to the rest of human history, which hardly lacks for propaganda, lies, conspiracy theories, and dangerous political ideas. I am convinced by the counter-argument and consider the fear of misinformation a poor excuse for abandoning the “value inclusive” ethic of intellectual tolerance adopted by librarians in the 20th century.

Because the arguments about misinformation are extensive and complex, I won’t try to make a conclusive case here.16 For now, I’ll just say that misinformation and conspiracy theories were hardly absent in the 1980s and 1990s when Pearl put Holocaust denial books in the Tulsa Public Library. There were Kennedy assassination conspiracies, flat earthers, Roswell space alien theories, and moon landing conspiracy theories to name a few.

Extremist groups were capable of organizing, agitating, and committing violence in the pre-internet days too. The Ku Klux Klan and the Weather Underground launched deadly terror campaigns in the 20th century, and the Southern United States were dominated by white supremacist ideologues spewing racist disinformation for hundreds of years. For anyone with a sense of historical perspective, it is hard to believe that a lack of disinformation in the past made it so much safer for librarians put Nazi books on library shelves back then than it is today due to the rise of Google, Facebook, and Twitter.

My third observation about Pearl’s statement is that her most significant concession to her critics is abandoning her trust in library patrons’ ability to figure out for themselves that Holocaust denial books are wrong.

Misinformation is the primary explanation that librarians now give for abandoning the uninhibited embrace of intellectual freedom that was more popular in the 20th century.

Rejecting the idea that librarians should be gatekeepers had been essential to Pearl’s ethos of librarianship prior to 2022. But, if she no longer can trust a library patron’s ability to evaluate a Holocaust denial book, how can she continue to validate their reading in anything else?

Dangerous ideas are not just found in Nazi books. They are in novels, popular literature, half-true, or mostly true works of non-fiction that get some things right and some things wrong by accident or on purpose. Who will help Pearl’s patrons navigate all that if they can’t even figure out for themselves that the Holocaust really happened?

The specific story that Pearl tells about how it would have been easier for a patron to correct the false information found in Holocaust denial books back in the 1980s is unconvincing. Yes, it’s possible that a reader in the pre-internet days would have gone to an encyclopedia or a reference librarian to ask if a book was telling the truth. But it’s also possible, and probably more likely, that he would have asked his buddies at the bar, or his wife, or that guy on talk radio. There were plenty of easily accessible unreliable sources of information back in the good old pre-Internet days when librarians still trusted their patrons. There always have been.

Although the Internet does put more unreliable sources right at our fingertips, it also makes it much easier for us to find reliable information. If someone wants to do a reality check on a book that she is reading today, it is much faster and easier to pick up her phone and read a couple Wikipedia articles than it would have been to walk over to the library to talk to the librarian back in the day (not that Wikipedia is perfect, of course, but it is as good as a reference librarian or the Encyclopedia Britannica for figuring out that you shouldn’t believe Holocaust denialism).

What Pearl misses in her statement is that it is not just anxiety about misinformation that makes librarians more distrustful of patrons today, but new theories of the American mind and the growing cultural distance between college educated librarians and less educated patrons.

Back in the McCarthy era, the librarians who wrote the Freedom to Read Statement trusted

Americans to recognize propaganda and misinformation, and to make their own decisions about what they read and believe. We do not believe they are prepared to sacrifice their heritage of a free press in order to be ‘protected’ against what others think may be bad for them. We believe they still favor free enterprise in ideas and expression.17

Those old-fashioned, outdated librarians believed that most American citizens were practical and freedom-loving. Americans wouldn’t be easily seduced by communist propaganda to abandon post-war American prosperity for the grim realities of collective life in Eastern Europe or China. Nor would they be easily tricked by authoritarian fantasies of racial unity offered by fascists.

In contrast, the critical theories adopted by many educated literary elites in the 21st century teach that the untutored American mind is an irrational repository of racism, misogyny, and homophobia.

Back in the mid-20th century, the librarians who wrote the Freedom to Read Statement rejected the intellectual paranoia of anti-communist culture warriors like McCarthy, who worried that any unorthodox opinions might subvert American democracy. In the 21st century, however, many left/liberal librarians have adopted a new culture of paranoia that reminds me of McCarthyism. Who knows, they worry, what will happen if librarians leave damaged, traumatized, or inherently racist American minds alone with misinformation?

The information environment looks so much more dangerous to librarians today than it did to Pearl and me when we were learning the ropes not only because they see countless sparks of misinformation being generated all around us by internet trolls, the Russians, the Chinese, anti-science propagandists, and right-wing provocateurs but also because they assume that the average American mind is filled with the dry tinder of white supremacy, soaked in the accelerant of transphobia and privilege. In such a terrifying world of information, librarians have to be on guard constantly against the misinformation fire that explodes out of control, and their rage against the value-neutral attitudes of intellectual openness and tolerance that Pearl and I grew up with is more comprehensible.

It is not just anxiety about misinformation that makes librarians more distrustful of patrons today, but new theories of the American mind and the growing cultural distance between college educated librarians and less educated patrons.

My fourth observation about Pearl’s concession statement is that it subverts the official reason for inviting her to the ALA conference and exposes the hypocrisy in the ALA’s new campaign against book bans. If the danger of misinformation has become more important than the danger of “viewpoint suppression” in the 21st century, why did the ALA start a new Unite Against Book Bans anti-censorship campaign in April 2022? Why is the ALA still fighting an outdated 20th century battle against viewpoint suppression instead of focusing librarians’ attention on the new problem of misinformation?

It’s true that a few conservative groups have started campaigns to try to get books that they don’t like out of libraries, especially if children have access to those books. But it is also true, as Pearl indicates, that the power of such groups to enforce viewpoint suppression is less significant today than it was back in the McCarthy era. According to librarian Sarah Hartman-Caverly, who compared the number of library books that have been challenged in the 2020s to the number of libraries in America,

“99% of libraries never receive a challenge, 99.99% of books are never challenged, and 99.9999% of library users never try to censor material.”18

In the digital age, there also are more ways for people to circumvent the limitations of their local library collection, and they are often assisted in doing so by the efforts of libraries elsewhere – for example, by the New York Public Library’s “Books for All” initiative to provide young patrons with digital access to books banned from their local library collection.19

The ALA seems to be sending librarians a mixed message. In her statement, Pearl accepted personal responsibility for failing to appreciate that danger of misinformation had invalidated her outdated commitment to value-neutrality, but I think that ALA also should be held partially responsible for Pearl’s confusion. They really should have warned her before she went to Washington:

“Dear Nancy,

Thank you for agreeing to participate in the Unite Against Book Bans panel. As you prepare your remarks on the evils of censorship, please be advised that the uninhibited distribution of misinformation poses an even greater threat to us today than does censorship.

Sincerely,

The ALA”

If only the ALA had sent Pearl the memo before the convention, we might have been spared the embarrassing spectacle of a mob of librarians celebrating the start of an anti-censorship campaign by going online to shame a respected colleague into silence for expressing an unpopular opinion.

But I’m trolling. The ALA’s priorities really aren’t confusing or contradictory if you are in the know.

Although Pearl admirably struggles with the “tension between the ‘value inclusive/include all viewpoints’ ethic and the ‘dangers of misinformation’ ethic” in her statement, she still fails to see (or declines to describe) the underlying principle that holds it all together for today’s ALA. It’s not the principled opposition either to censorship or to misinformation, but the ideological consensus of the most vocal 21st century librarians that gives coherence to the ALA’s projects.

Many of the librarians yelling at Pearl on Twitter kept saying in frustration “no, it’s not complicated” in response to Pearl’s observation that “it’s much more nuanced and it’s much more difficult than one often tends to think that it is.” From their perspective, it isn’t. All you have to do is abandon the crazy idea that ‘both sides’ might have valid points to make. The tensions identified by Pearl are not to be resolved by philosophical reflection but by being on the right team and never passing the ball to anyone wearing the wrong jersey.

For the 21st Century Librarian Action Figure, anti-censorship and anti-misinformation have become two weapons to be deployed against the forces of evil at different times and places.

When the bad guys try to take good books off of library shelves, librarians unsheathe the sword of anti-censorship to protect patrons’ right to read what librarians have selected for them. When the bad guys try to spread bad ideas by writing dangerous books, librarians pick up the cudgel of anti-misinformation to crush them before they disturb the minds of vulnerable patrons.

The underlying incompatibility between our weapons seldom becomes a problem because they are used at different stages in the process of cultural exchange. The fight against censorship happens after books have been selected and shelved and are challenged by “right-wing extremists.” The fight against misinformation happens earlier, in collection development, when books with misinformation about COVID, global warming, or various right wing, conservative, or heterodox viewpoints are kept off the shelves.20 Often, the fight against misinformation happens before librarians even get involved when publishers decide not to publish books with dangerous ideas.21

The deep (and I think irresolvable) contradiction between claiming the high ground of defending intellectual freedom while fighting a gutter war against misinformation can be ignored as long as famous librarians don’t push our noses in it by asking provocative questions at national conventions.

It is much easier to merge an ideological battle against right wing extremists with the Freedom to Read when us frumpy old-timers who still remember the days when librarians really believed that “ideas can be dangerous; but that the suppression of ideas is fatal to a democratic society” can be shushed.

John Wenzler is a librarian at Cal State East Bay.

Continue reading John Wenzler’s series for Freedom to Read Week, Nancy Pearl and Me: Reflections on the Changing Ethos of American Librarianship:

Part 1: From Action Figure to Antihero (February 20, 2025)

Part 3: ALAlienation (February 27, 2025).

References

American Library Association, and Association of American Publishers. “The Freedom to Read Statement,” June 25, 1953. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/freedomreadstatement.

Berry, John N. “Nancy Pearl: LJ’s 2011 Librarian of the Year.” Library Journal, January 16, 2011. https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/nancy-pearl-ljs-2011-librarian-of-the-year.

Bogan, Kelsey. “(3) The Harm It Caused...” Tweet. Twitter, July 1, 2022. https://x.com/kelseybogan/status/1542708568591421441.

———. “Addressing Problematic/Harmful Books in the School Library.” Don’t Shush Me! (blog), March 26, 2023. https://dontyoushushme.com/2023/03/26/addressing-problematic-harmful-books-in-the-school-library/.

———. “At an ALA Session about ‘Uniting Against Book Bans’ Today There Was a Sentiment ...” Tweet. Twitter, June 25, 2022. https://x.com/kelseybogan/status/1540809694721236993.

———. “Don’t Shush Me!” Don’t Shush Me! (blog), June 23, 2015. https://dontyoushushme.com/about/.

Bookstax [@bookstax]. “@kelseybogan @UABookBans @Nancy_Pearl @JasonReynolds83 Like for a Regular Library’s Collection ...” Tweet. Twitter, June 25, 2022. https://x.com/bookstax/status/1540826861483073536.

Cook, Elizabeth Kaye, and Melanie Jennings. “Scenes From The Literary Blacklist.” Persuasion, October 13, 2024. https://www.persuasion.community/p/scenes-from-the-literary-blacklist.

Hartman-Caverly, Sarah. “Conservatives Censor Where It Counts.” Substack newsletter. Heterodoxy in the Stacks (blog), February 20, 2023. hxlibraries.substack.com/p/conservatives-censor-where-it-counts.

———. “Make Book Bans Boring Again.” Substack newsletter. Heterodoxy in the Stacks (blog), June 6, 2024. hxlibraries.substack.com/p/make-book-bans-boring-again.

Hear-Me-Roar🐯🗽🩸🦷🇺🇦 ☮️ [@sara4SF]. “@kelseybogan @mls_amy @UABookBans @Nancy_Pearl @JasonReynolds83 There Are Books w/Historical Facts...” Tweet. Twitter, June 26, 2022. https://x.com/sara4SF/status/1541059988914745344.

jessica the messica (she/her) @cupcakeplzz. “I Went to #alaac22 for Two Days and Brought Home COVID, a ‘Both Sides’ Argument from a Prominent White Woman in the Field.” Tweet. X (Formerly Twitter), June 28, 2022. https://x.com/cupcakesplzz/status/1541877975892856832.

Ronson, Jon. So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed. New York: Riverhead Hardcover, 2015. https://search.worldcat.org/title/905346081.

Slater, Dashka (@DashkaSlater). “Book People, We Need to Talk about Libraries, Free Speech, Fascism & What Happened at ALA. Because the Thicket That @Nancy_Pearl @JasonReynolds83 and @UABookBans.” Tweet. Twitter, June 26, 2022.

Spratford, Becky. “RA for All: ALA 2022: Final Thoughts.” RA for All (blog), July 1, 2022. https://raforall.blogspot.com/2022/07/ala-2022-final-thoughts.html.

The New York Public Library. “The New York Public Library To Launch Nationwide ‘Books For All: Protect the Freedom to Read’ In Response to Unprecedented Rise in Censorship.” Accessed October 13, 2024. https://www.nypl.org/press/new-york-public-library-launch-nationwide-books-all-protect-freedom-read-response.

Walter, Scott (@slwalter123). “Another Reminder That Libraries Are Not Neutral & Never Have Been; the Belief That All Should Have Access to Information Necessary to Be an (Accurately) Informed Citizen Is a Fundamentally Political Belief & @Nancy_Pearl Should Know Better #ALAAC22.” Tweet. Twitter, June 26, 2022.

Wiemer, Liza (@LizaWiemer). “I Spoke at Length Today with @JasonReynolds83 Regarding #ALAAC22’s Banned Books Discussion, Holocaust Education and Holocaust Denial Books. Here Is My Statement.” Tweet. Twitter, 2022.

Williams, Dan. “The Fake News about Fake News.” Boston Review, June 7, 2023. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/the-fake-news-about-fake-news/.

———. “The Misinformation Wars - a Reading List.” Conspicuous Cognition (blog), August 17, 2024. https://www.conspicuouscognition.com/p/the-misinformation-wars-a-reading.

Wu, Tim. “The First Amendment Is Out of Control.” The New York Times, July 2, 2024, sec. Opinion. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/02/opinion/supreme-court-netchoice-free-speech.html.

Yorio, Kara. “With a Joyful Return to In-Person, ALA Annual Hosts a Censorship Discussion. A Twitter Controversy Ensued.” School Library Journal, July 1, 2022. https://www.slj.com/story/with-a-joyful-return-to-In-Person-ALA-annual-hosts-a-censorship-discussion-a-twitter-controversy-ensued.

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer-reviewed, all posts and comments must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, submit the Heterodoxy in the Stacks Guest Submission form in the format of a Microsoft Word document, PDF, or a Google Doc. Unless otherwise requested, posts will include the author’s name and the commenting feature will be on. We understand that sharing diverse viewpoints can be risky, both professionally and personally, so anonymous and pseudonymous posts are allowed.

Thank you for joining the conversation!

Bogan, “Don’t Shush Me!”

Bogan, “Addressing Problematic/Harmful Books in the School Library.”

Bogan, “At an ALA Session about ‘Uniting Against Book Bans’ Today There Was a Sentiment ...”

Walter, “Another Reminder That Libraries Are Not Neutral & Never Have Been; the Belief That All Should Have Access to Information Necessary to Be an (Accurately) Informed Citizen Is a Fundamentally Political Belief & @Nancy_Pearl Should Know Better #ALAAC22.”

Slater, “Book People, We Need to Talk about Libraries, Free Speech, Fascism & What Happened at ALA. Because the Thicket That @Nancy_Pearl @JasonReynolds83 and @UABookBans stumbled into is one that fascists have long exploited. Luckily the great Hannah Arendt can guide us out.”

Hear-Me-Roar🐯🗽🩸🦷🇺🇦 ☮️ [@sara4SF], “@kelseybogan @mls_amy @UABookBans @Nancy_Pearl @JasonReynolds83 There Are Books w/Historical Facts...”

Bookstax [@bookstax], “@kelseybogan @UABookBans @Nancy_Pearl @JasonReynolds83 Like for a Regular Library’s Collection ...”

jessica the messica (she/her) @cupcakeplzz, “I Went to #alaac22 for Two Days and Brought Home COVID, a ‘Both Sides’ Argument from a Prominent White Woman in the Field.”

Kara Yorio, SLJ

My assertion that Reynolds changed his mind is based on a report by Liza Wiemer on Twitter. Wiemer, “I Spoke at Length Today with @JasonReynolds83 Regarding #ALAAC22’s Banned Books Discussion, Holocaust Education and Holocaust Denial Books. Here Is My Statement.”

Spratford, “RA for All.”

Bogan, “(3) The Harm It Caused...”

Yorio, “With a Joyful Return to In-Person, ALA Annual Hosts a Censorship Discussion. A Twitter Controversy Ensued.”

Berry, “Nancy Pearl.”

For a recent example, see: Wu, “The First Amendment Is Out of Control.”

The English philosopher, Dan Williams, and his blog Conspicuous Cognition is a good starting point for exploring the intellectual critique of the misinformation thesis. See: Williams, “The Fake News about Fake News.” Or Williams, “The Misinformation Wars - a Reading List.”

American Library Association and Association of American Publishers, “The Freedom to Read Statement.”

Hartman-Caverly, “Make Book Bans Boring Again.”

“The New York Public Library To Launch Nationwide “Books For All.”

Hartman-Caverly, “Conservatives Censor Where It Counts.”

Cook and Jennings, “Scenes From The Literary Blacklist.”

Thanks, John, for another excellent article in this series. This is a riveting account of a "purity spiral" in action in a major professional association, revealing much about the values and priorities of those involved in the "spiral" or the mobbing. The particular controversy in question here, books on Holocaust denialism, could be replicated with numerous other controversial topics that become taboo, and supposedly incapable of adult discussion because of "harm" (and the concept creep for "harm" has become noticeable in our field in recent years).

I'm glad to see that you focused as much as you did on the fraught term "misinformation" and many librarians' casual or careless use of it. Of course, the word is used casually or carelessly by many in the broader culture, and notoriously and often by politicians, journalists, and owners of large social media platforms, who do much to amplify conspiracy theories, half-truths, lies, and falsehoods, creating a polluted information environment. I'm thinking especially here of (X) and its algorithms and the behavior of its owner, but other platforms create similar conditions for tribalistic distortions of reality.

As for the term "misinformation" itself, I'd recommend anyone who's interested in a better conceptual approach to it to read Dan Williams' valuable substack, Conspicuous Cognition, and especially this article:

https://www.conspicuouscognition.com/p/what-is-misinformation-anyway

Also, scholar of conspiracy theories Joe Uscinski has urged a cautious approach to studying and writing about "misinformation"--librarians are now at the point where they think they can use reductive methods to teach about it when it actually requires much more (and broader) considerations about social change, belief formation, and the role of inquiry itself. Uscinski's recent co-authored article urges greater care since there's a careful delineation to be made between Information that is objectively false, and information that is subjectively believed because of the receiver's own cognitive biases or tribal affiliations.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2352250X24000022

Books about Holocaust denialism like any books that counter objective facts have a place in public places. Those places can be organized in such a way that factual materials are there to counteract the denial. Otherwise, the denialist books circulate in strange places where they are hard to discount. What does it mean for a library to have books? Does it mean that every librarian attests to the content of each book? Would a Protestant librarian approve a book about the Vatican? Would an atheist librarian approve a book about the Lives of the Saints?

Here is the LC on the topic of Holocaust denial:

https://id.loc.gov/authorities/subjects/sh96009499.html