From Action Figure to Antihero

Nancy Pearl and Me: Reflections on the Changing Ethos of American Librarianship. Part 1 in a 3-part series by John Wenzler for Freedom to Read Week.

John Wenzler, guest contributor.

If there are any persons who contest a received opinion, or who will do so if law or opinion will let them, let us thank them for it, open our minds to listen to them, and rejoice that there is someone to do for us what we otherwise ought, if we have any regard for either the certainty or vitality of our convictions, to do with much greater labor for ourselves.

John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, 18561

Why compare myself to Nancy Pearl?

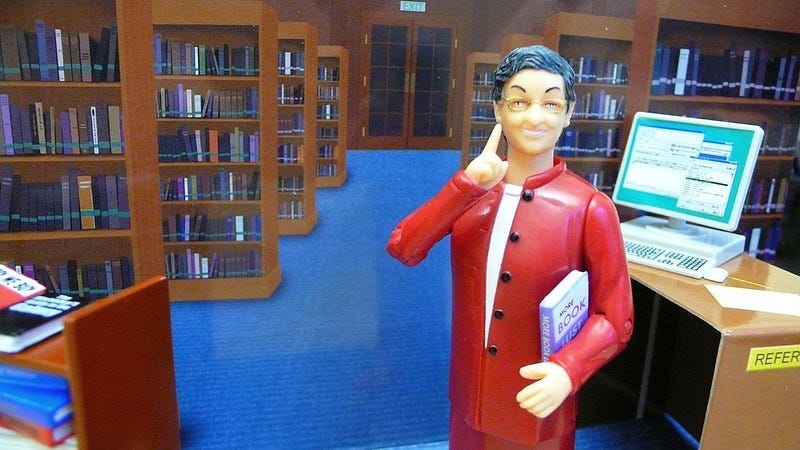

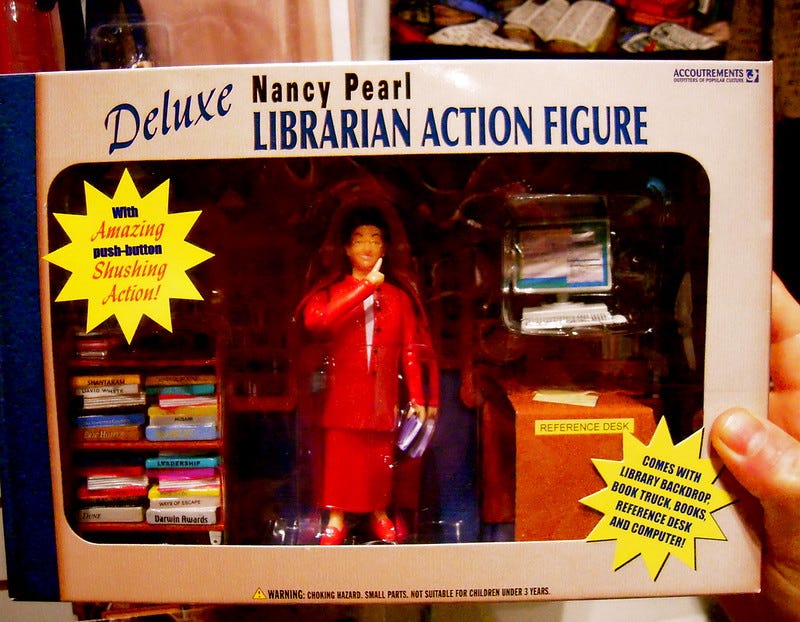

Pearl, “America’s Librarian,” may be the most famous librarian in the world today. Not only has she has written several popular Book Lust books on contemporary literature, but a children’s book, Library Girl: How Nancy Pearl Became America's Most Celebrated Librarian, has been written about her.2 She’s received numerous awards, including Library Journal’s 2011 Librarian of the Year award, and the 2021 Literarian Award for Outstanding Service to the American Literary Community.3 Pearl is frequently heard on national radio interviewing authors and talking about books. She even served as the model for an iconic Librarian Action Figure toy.

As for me, I’ve toiled at library jobs for the last 30 years in comfortable obscurity. You won’t hear me on the radio, see my face on a popular doll, or read about my awards on Wikipedia.

So, why Nancy “and me”?

I write about Pearl because her experience helps me understand my own. Sometimes we see ourselves better in that face on the stage, exposed by the spotlight, and suffering the slings and arrows of popular scrutiny. For me, Pearl’s career—especially her semi-cancellation at American Library Association (ALA) Convention in 2022—helps me understand my growing sense of alienation from my library colleagues. Her trials and tribulations help me explain that feeling in my gut that something has changed in the ethos of the profession during the last ten years that I don’t really understand and that I am unwilling to endorse.

I’ll start with two frames for explaining what I learned about myself from exploring Pearl’s career. The first is the experience that comes from going to a conference and realizing that something has changed while you weren’t paying attention. There’s a sudden insight that many librarians no longer believe in fundamental values that seemed so obvious and natural in the recent past. There’s a feeling of mutual betrayal that leads to questions like:

“What’s wrong with these librarians today? Or what’s wrong with me? Should I accept or reject these disorienting revisions to our professional priorities?”

The second frame situates our experience (Pearl’s and mine) within historical tensions in the values of American librarianship. On the one hand, public libraries celebrate the American spirit of self-reliance and rugged individualism. The library doesn’t tell you what to think; it gives you tools to figure things out for yourself. Andrew Carnegie, the American self-made man par excellence, donated millions of dollars to build thousands of public libraries across the country because a library gave him what he needed to make himself—“libraries give nothing for nothing; they only help those who help themselves”—and he wanted everyone else to have the same opportunity.4

But American public libraries also are collective agencies dedicated to the moral improvement of the community. In the early days, they often were founded by community elites in the hope of improving the morals of poor, working-class immigrants. Free public libraries would divert the attention of the uneducated away from dime novels full of sex, violence, and political radicalism and encourage them to read morally elevating literature instead.5 There is a fundamental conflict in American librarianship between trusting library patrons to think for themselves and teaching them to think what the educated elite want them to think.

Pearl (born in 1945) is 20 years older than me, but we both became librarians in the second half of the 20th century when librarians were influenced by laissez-faire, libertarian approaches to librarianship that emphasized patron self-reliance. In library school during the 1990s, I was taught the “Give ‘Em what they want!” philosophy of collection development popularized by Charles Robinson and the Baltimore County Public Library in Maryland.6 Robinson bought multiple copies of bestsellers to increase circulation as much as possible. He claimed that he was giving patrons what they really wanted to read instead of what snooty librarians wanted them to want.

As a student, I chafed against “Give ‘Em what they want!” I didn’t sign up for librarianship to pander to market demand like a corporate manager. If that was what I wanted to do with my life, I thought, I could make more money doing it somewhere else. I had assumed that being a librarian was a higher calling, a form of public service that transcended the soulless commercialism of American capitalism. Now, in 2025, I have to admit that Robinson’s laissez-faire approach at least had the virtue of respecting the intellectual autonomy of library patrons, a virtue that I either took for granted or ignored back when I was young and idealistic.

In the 21st century, especially since the market collapse of 2008, a strong reaction against the libertarian, neoliberal attitudes of the 1990s has contributed to the reemergence of a politically oriented style of librarianship. In many librarians, especially in those who are intellectually engaged with professional leadership, I observe an intense ethos of moral perfectionism devoted to social justice, anti-racism, equity, and inclusion. Although I grudgingly admire the naïve dream that librarians can fix the world, that dream is tearing me apart and souring my relationship to colleagues. As I see it, the growing moral earnestness of the profession undermines librarians’ trust in the intellectual competence of the average American citizen and sabotages our commitment to their intellectual freedom.

There is a fundamental conflict in American librarianship between trusting library patrons to think for themselves and teaching them to think what the educated elite want them to think.

In the Twitter attack on Nancy Pearl at the ALA convention in 2022, l saw a celebrated and well-respected librarian get twisted, turned, and yanked apart by this transformation in the culture of American Librarianship – that’s how her experience illuminates my own.

Book Lust & the Rule of Fifty

For avid readers, it’s dangerous to pick up Pearl’s Book Lust: Recommended Reading for Every Mood, Moment, and Reason if you have any work that you want to do in the next few months.7 I’ve been skimming it for research purposes, and I already have four new titles waiting for me on my Kindle and three ILL requests in at the library.

The breadth of Pearl’s reading is awe-inspiring. It seems like she’s read everything worth reading published in English since 1970. It’s not just novels. Although you won’t find many academic monographs in Book Lust, it includes non-fiction titles for general readers that I would expect to find in a public library. Her selection of books on the Middle East is particularly compelling today. As she argues, you probably will learn much more about what is happening over there by reading a few of her suggested titles than by watching the talking heads yell at each other on cable.

It’s obvious that Pearl enjoyed the books that she recommends, and her descriptions are crafted to whet the appetite of fellow readers. For example, I’ve never heard of the novelist Eric Kraft, who Pearl considers “too good to miss,” but how could I not run out (to Amazon) to get one of his books after she tells me:

“Think of Proust with a sense of humor, or on drugs.”8

Book Lust is the perfect title because Pearl doesn’t try to elevate reading into a moral duty or a utilitarian investment in self-improvement. She believes that reading benefits the soul by giving us insight into the minds of others, but she also knows that’s not why we read, just as we don’t have sex because we want to increase the industrial capacity of the economy. We (librarians) won’t get people to read more by telling them that reading is good for them but by making it fun and exciting.

Pearl’s “rule of fifty” illustrates her respect for the intellectual autonomy of readers. She doesn’t expect anyone to read out of a sense of obligation: “Believe me, nobody is going to get any points in heaven by slogging their way through a book they aren’t enjoying but think they ought to read.” Nevertheless, she asks readers to exert themselves somewhat to develop their critical muscles. She advises us that:

If you’re fifty years old or younger, give every book about fifty pages before you decide to commit yourself to reading it, or give it up. If you’re over fifty, which is when time gets even shorter, subtract your age from 100 – the result is the number of pages you should read before deciding.9

This reminds me of Carnegie’s admonition that the library “gives nothing for nothing.” You have to put effort into it, but the goal is to develop your own sense of judgment instead of conforming to judgments that someone else would impose on you. Pearl thus tries to navigate between the simple pandering of “give ‘em what they want” and the paternalistic assumption that librarians are moral authorities sifting the good from the bad for the benefit of their patrons.10

Fame & Controversy

The success of Book Lust, Pearl’s self-deprecating sense of humor, and a couple of quirky twists of fate transformed Pearl into a celebrity at the beginning of the 21st century. As Pearl earned national recognition, however, she also experienced a few controversies. The backlash against her fame was limited (at least before 2022), but reflected a growing sense of unease felt by some librarians who worried that Pearl’s image undermined the moral seriousness of the profession.

In 1998, Pearl initiated the "If All of Seattle Read the Same Book" program. It may have been the first successful citywide book club. Sales of the chosen novel, The Sweet Hereafter by Russell Banks, spiked and generated citywide conversation. Seattle’s success led to imitation, and hundreds of cities now have annual One City One Book programs. Controversy ensued when One City One Book got to New York in 2002 because the New Yorkers couldn’t agree on what to read. A panel of 15 librarians and booksellers were divided between a memoir about an author with a Black father and a Jewish mother and a novel about a Korean immigrant. Some worried that the story about the Jewish son would offend Hasidic Jews, and others worried that the story about the Korean immigrant would offend Asians.

The messy, unresolved dispute led to grumbling about the whole idea of One City One Book from New York intellectuals. “I don’t like these mass reading bees,” Harold Bloom complained, “It is rather like the idea that we are all going to pop out and eat Chicken McNuggets or something else horrid at once.”11 Others complained about the “groupthink” of trying to get everyone to read the same book.

Even before things got messy in New York, Pearl understood that citywide reading programs were bound to disappoint if they were freighted with too much moral significance. She warned that “this is a library program, it's not an exercise in civics, it's not intended to have literature cure the racial divide.” She responded to the New York controversy by observing that

"It's turned into something not to do with literature but to do with curing the ills in society, and while there is a role for that, to ask a book to fit everybody's agenda in talking about particular issues just does a disservice to literature."12

From Pearl’s perspective, the citywide book clubs, like her Book Lust reviews, were intended to entice people into trying something new. They weren’t meant to impose required reading for civic improvement on citizens. I doubt that she would have asked anyone to violate her 50-page rule for the sake of a city book club. If readers started a city recommended book and decided that it wasn’t for them, no one was going chastise them for moving on to something else. But the controversy reflected some librarians’ desire for moral uplift that was at odds with Pearl’s approach.

Librarian Action Figure

Pearl’s most unique claim to fame, the Librarian Action Figure, also became a source of controversy. The idea came from a chance encounter at a dinner party in Seattle. Pearl met the owner of a novelty toy company that was already selling a line of ironic plastic dolls such as the Jesus Action Figure (the deluxe version includes loaves and fish and jugs of water and wine so that Jesus can perform his miracles). After the dinner party, one thing led to another, and Pearl became the model for a Librarian Action Figure that included “Amazing, push-button, Shushing Action!” The deluxe version includes a book truck, a reference desk, and a computer terminal.

The LAF (as Pearl calls it) generated significant press attention, often focused on the belief that many librarians were annoyed because Pearl had leaned into “frumpy,” shushing stereotypes. In a 2003 National Public Radio (NPR) interview with Pearl, Melissa Block claimed to have “field-tested” the LAF by visiting libraries in Washington DC and asking librarians about it. Per Block, “there was a lot of librarian rage when they looked at this figure.” Katherine Baer, the NPR Librarian, complained:

“This shushing part is what bothers me the most about the doll. Well, if you go into libraries today, they’re not quiet, they’re very active. There’s, you know, everything with computers and all kinds of technology … it’s just a myth about the shushing. I mean, I resent it.”13

I’m inclined to wonder if the blowback existed primarily in the imagination of journalists looking for a story angle, but Pearl acknowledged that she had received direct complaints. Later, she summarized the negative response by saying:

“Well there were, I would say, maybe thirty-eight or thirty-nine librarians around the world who had no sense of humor. And every one of them wrote to me: ‘You have set the librarian profession back twenty years.’”14

In 2003, Pearl saw the moralistic scolds as an eccentric minority who could be dismissed with gentle humor. By 2022, her self-confidence in the face of humorless criticism would fade.

Amazon Book Lust Rediscoveries

Amazon Book Lust Rediscoveries was a 2012 project initiated by Pearl. Before she partnered with Amazon, Pearl had been looking for a publisher to re-issue some of her favorite Book Lust recommendations that were out of print. After 20 or so publishers turned her down, Amazon said yes. They published about 15 titles between 2012 and 2014. You can still find them by searching for “Book Lust Rediscoveries.” I recommend it. I’ve got two of them so far, The Lion in the Lei Shop, and Plum & Jaggers.

In addition to getting the books republished, Pearl wrote introductions, explaining why she loved these books so much. She seems to be focused on the idea of memory, at least in the two introductions that I’ve read so far—she says that she often has a better memory for what happened in the books she’s read than for events in her own life and sometimes she even gets them confused. I didn’t hear about the Book Lust Rediscoveries back in 2012, but now that I’ve rediscovered them, I’d call them a welcome addition to my literary life.

Nevertheless, Pearl’s decision to collaborate with Amazon generated more intense blowback than her decision to model for the LAF. In reviewing the press coverage of the controversy, I don’t see any criticism of Pearl’s specific project. No one complained that it was a bad for a few authors to get more royalties or that it was problematic for readers to have easier access to a few interesting titles. The problem was that many librarians and others associated with the literary world believed that Amazon was dangerous to bookstores, libraries, and authors. They worried that Amazon was “cynically buying a local hero’s endorsement to cover up its aggressive tactics.” Per the New York Times:

The Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association, which just gave Ms. Pearl its lifetime achievement award, described the reaction among its members as ‘consternation.’ In Seattle, it was front-page news. ‘Betrayal’ was a word that got used a lot.15

The critics believed that Pearl had allowed Amazon to Nancy-Pearl-wash its image by giving it a feel-good story to distract attention from all the horrible stuff that it was doing elsewhere.

To me, the complaints reflect a poor opinion of the reading public. Leaving aside the difficult question of whether the critics are correct to believe that Amazon was/is bad for literature, I believe that most readers are sophisticated enough to evaluate Amazon as a whole. They won’t be fooled by superficial PR projects—if that is what Book Lust Rediscoveries really was. Ultimately, the complaint dissolves into mere guilt by association. Because Amazon is bad in the eyes of her critics, they believe Pearl sullied herself and the profession of librarianship by working with them even if she accomplished something useful by doing so.

For Pearl, the backlash against Book Lust Rediscoveries was more difficult to handle than the backlash against the LAF. The intense negative response shook her self-confidence. She told the Times: “I knew the minute I signed the contract that there would be people who would not be happy, but the vehemence surprised me.” She respected the views of her critics but ultimately stood her ground:

“I understand and sympathize with the concerns about Amazon's role in the world of books. If I had to do this deal all over again ... well, it's a hard question. But I would still want these books back in print.”16

For me, the Amazon controversy serves as a prelude to the controversy sparked by her comments at the 2022 ALA Conference. In 2022, she again was shocked and surprised by the intense negative response to her actions. She again sympathized with the concerns of her unexpected critics—but in 2022, she no longer felt confident enough in her own views to stand her ground.

2022 ALA Conference – Unite Against Book Bans

Principled proponents of free speech consider the freedom to read, write, and say what we want an inalienable right rather than a mere means to achieve other ends.

In June 2022, Pearl was invited to participate in a panel at the national ALA convention in Washington DC by Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the Director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom (OIF). The panel focused on the “Unite Against Book Bans” initiative launched by the ALA in April 2022 to fight increasing efforts to challenge library books in the 2020s.17 Pearl, who had dedicated her career to promoting the joys of a diverse literary life, was an obvious choice to speak about the importance of the freedom to read. However, some of Pearl’s comments on this theme unintentionally enraged many librarians.

During the panel discussion, Pearl argued that we can’t demonstrate that we are fully opposed to book bans unless our libraries include books that are offensive to many of our patrons and, most importantly, offensive to ourselves:

I’ve always thought there should be a T-shirt or poster in every library that says, ‘There is something in my library to offend everyone,’ because it wouldn’t be a library if there weren’t. When I was in charge of collection development at the Tulsa Public Library, one of the hardest things was facing up to your own prejudices. Like what did I not want to add in the collection? Personally, I did not want to add Holocaust denying books. That was offensive to me. Did I think we needed them? Sad to say, yes. But you know we talk about we shouldn’t ban books, it’s much more nuanced, and it’s much more difficult than one often tends to think that it is.18

This statement quickly led to the condemnation of Pearl on Twitter that had such a profound effect on me. But before I discuss the Twitter pile-on, I should explain why I endorse Pearl’s argument, and the extreme example that she used to make her point.

Pearl’s comments express what free speech advocates call a principled defense of free expression. Principled proponents of free speech consider the freedom to read, write, and say what we want an inalienable right rather than a mere means to achieve other ends. Our commitment to free speech is principled when we defend our mortal enemies’ right to say terrible things that we hate just as strongly as we defend our friends’ right to express beautiful truths that we love. It’s a difficult, emotionally challenging commitment and probably impossible for anyone to fully achieve.

Pearl highlights the challenge by using a provocative example. Since World War II, Nazis and their apologists have symbolized pure political evil. Supporting a Nazi’s right to free expression is a good way of demonstrating that you won’t discriminate against anyone else for their political views regardless of how much you disagree with them.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) defense of a Nazi group’s right to hold a demonstration in Skokie, IL where many Holocaust survivors lived in 1977 has become a powerful example of free speech activism because it demonstrated the strength of the ALCU’s commitment to the principals of liberty. David Goldberger, the Jewish lawyer who took the case for the ACLU argued that:

“Central to the ACLU’s mission is the understanding that if the government can prevent lawful speech because it is offensive and hateful, then it can prevent any speech that it dislikes.”19

Pearl essentially makes the same case for librarians—our willingness to support the free distribution of ideas that we find personally reprehensible gives credibility to our promise that our political preferences, cultural values, or religious beliefs will not limit our commitment to give patrons access to reading materials that respond to their interests.

Pearl’s position also reflects her faith in the ability of library patrons to make their own judgments. Pearl’s career had been devoted to encouraging readers to develop their own critical faculties by enticing them to read widely and making up their own minds about books. In a 2011 interview, Pearl rejected the “old” idea that librarians should be “gatekeepers.” Instead, librarians should “validate a patron’s reading.”20

The gatekeeper theory of librarianship relies on the librarian’s judgment to keep the bad stuff out of the hands of patrons. There are two problems with it. First, librarians are not omniscient and infallible. There’s no way that we can credibly promise that everything that we put on our shelves is good and true. Library non-fiction shelves are filled with lies, half-truths, outdated theories, misinterpretations, and contradictory opinions not because librarians are bad at their jobs but because the world is complex, confusing, and hard for the human mind to understand. Second, the gatekeeper theory assumes that patrons will depend on the librarian’s judgment instead of developing their own. But patrons don’t live in the library; they live in a rich, diverse, and confusing information environment. Every time that a reader hears about a new book, they can’t and won’t call a librarian to ask if it is OK for them to read it.

If finding a Holocaust denial book in an online forum or on a library shelf turns the average American citizen into a Nazi, or if finding the Communist Manifesto transforms them into a Marxist revolutionary, American democracy is doomed regardless of what any librarian does. By encouraging readers to develop their ability to evaluate what they read either inside or outside of the library and by challenging them with provocative and controversial material, librarians can do more to support democracy than by building gated islands of safe books that will be ignored by those who don’t already share the librarians’ opinions.

Of course, my argument about librarianship and censorship is complicated by the limited power possessed by librarians. Fortunately, we lack most of the authority of traditional censors. We can’t search your house and throw you in the dungeon if we find a book critical of the government on your kitchen table. We can’t even prevent other libraries, bookstores, or online platforms from distributing books and ideas that we choose not to add to our own collections. And, because space and funds are limited, librarians always have to make difficult decisions about what to collect and what not to collect. Why not use some of the necessary discretion required for collection management to distinguish between legitimate and illegitimate ideas? That’s not censorship, right? We can’t stop Holocaust deniers from spreading their lies in obscure corners of the Internet, but we can, at least, deny them the spurious legitimacy of putting their books on a library shelf next to serious, scholarly studies.

For me, however, this is simply a more subtle form of censorship. In his classic essay, “Not Censorship but Selection,” which is available on the ALA website, Lester Asheim warns librarians that it is easy to fall into the habit of using our control over library collections for censorious ends if we have a paternalistic attitude towards our patrons. He argues that

“The positive selector asks what the reaction of a rational intelligent adult would be to the content of the work; the censor fears for the results on the weak, the warped, and the irrational.”

Like Pearl, Asheim wants to validate the critical judgment of readers instead of using his own judgment to protect them from ideas that might harm them. He argues that a genuine commitment to the freedom to read requires “faith” in the common man and woman:

“Selection seeks to protect the right of the reader to read; censorship seeks to protect – not the right – but the reader himself from the fancied effects of his reading. The selector has faith in the intelligence of the reader; the censor has faith only in his own.”21

In practical terms, how does a librarian’s faith in the reader’s intelligence influence decisions about whether or not to select books that deny the Holocaust? When confronted with bad ideas, I think that librarians have to account for their cultural salience. Human minds have proposed millions of wrong-headed, dangerous, and discredited ideas over the course of history. Most of these—Ptolemaic astronomy, phrenology, phlogiston theory, or outdated medical protocols, to name a few—have been consigned to the dustbin of history. Almost no one believes in them anymore, and they exert no cultural or political influence in the 21st century. For such abandoned ideas, benign neglect seems appropriate. It would be a poor use of community resources to buy a new defense of phrenology instead of another copy of a bestseller that has 50 holds on it.

Nor is it necessary to censor or discourage the study of such ideas. If a patron comes in with a strong interest in phlogiston theory, librarians can assist them in their research through ILL and online resources. Of course, if 5 or 6 patrons come into the library to research phlogiston, a librarian ought to reevaluate the assumption that it is a dead idea.

The key difference between censorship and positive selection in Asheim’s sense becomes evident when librarians confront bad ideas that are also influential in their community. Personally, I believe that Robert F. Kennedy’s theories about vaccines are just as wrong as Ptolemy’s theories about the motion of the earth and more dangerous because Kennedy’s ideas may convince parents to make poor choices about the health of their children. Similarly, Donald Trump’s theory that the 2020 election was stolen is obviously wrong and potentially damaging to America’s democratic institutions. Nevertheless, I have to acknowledge that Kennedy’s and Trump’s theories—unlike Ptolemy’s—are widely influential in 21st century American discourse.

For library censors, who trust only their own judgment, it especially important to protect the community from popular bad ideas. Patrons must be warned that populist misinformation doesn’t belong in the realm of legitimate public discourse by excluding it from the public library. The “weak, the warped, and the irrational” who find their way into our libraries must be protected from picking up crazy ideas about vaccines during their visits.

For positive Asheimian selectors, in contrast, the prevalence of Kennedy’s theories in contemporary society makes it especially important to include them in our collections. Citizens ought to have the opportunity to read what many of their fellow citizens believe even if librarians consider those beliefs false and dangerous. For patrons who seek out such material, it is probably better for them to find it in a public library where they will be exposed to counterarguments instead of in a partisan echo chamber. For patrons who disagree with Kennedy, they may be able to develop more convincing counterarguments if they read what he believes in his own words.

Ultimately, a commitment to maintaining open-minded collections depends on Asheim’s faith in the public’s judgment, and I don’t understand how any librarian who lacks that faith can also profess belief in the freedom to read.

So, should Holocaust denial be treated with benign neglect like phrenology or added to public library collections like Kennedy’s vaccine books? That’s a judgment call that will differ for librarians at different times and places. I trust Pearl’s judgment that she needed to add it to the collection when she worked at the Tulsa Public Library in the 1980s. As a librarian in California in the 21st Century, I’d say that there is little need for non-research libraries to add Holocaust denial titles to their collections. Here, it seems to live on primarily as a prototypical example of “evil belief” that almost no one publicly endorses.

However, a recent event complicates that judgment for me and further illustrates the challenges of a censorious approach to library collections. On September 2, 2024, Tucker Carlson, a popular right-wing broadcaster, published a video interview with Darryl Cooper, a podcast historian who goes by the name, Martyr Made. As of December 5, 2024 when I accessed the video on x.com, it had been viewed 34.8 million times.22 In the interview, Cooper makes several controversial assertions about World War II. For example, he calls Winston Churchill the “chief villain” of the war. Because Churchill refused to negotiate a peace treaty with Germany (as desired by Hitler per Cooper) after the Nazis had defeated France, he transformed a European war into a World War that led to the death of millions of people.

After the interview was posted, several commentators accused Cooper of Holocaust revisionism and criticized Carlson for platforming him.23 On September 8, 2024, Cooper responded to the criticism on his podcast. He denied denying the Holocaust and referred listeners to an earlier podcast “Fear & Loathing in the New Jerusalem” in which he described in detail how the Nazis had slaughtered the Jews in Ukraine and quoted extensively from the memoirs of Holocaust survivors.24

Are Cooper’s critics correct to call him a Holocaust Denier or a Nazi apologist? I don’t know. In my opinion, the ethnonationalist political ideas expressed by Carlson and Cooper in the interview are dangerous and undemocratic, but they never deny that the Holocaust happened even as they advance controversial theories about why it happened. I am not enough of an expert in World War II history to evaluate whether the interview should be considered fascist propaganda as Cooper’s critics charge.

However, a librarian who trusts the judgment of patrons doesn’t have to make that decision. A podcaster who gets 30 million views on x.com is influential enough to get added to library collections and exposed to the scrutiny of library patrons regardless of whether he is a Holocaust denier or not. Libraries should provide access to the controversy so that the public can decide for itself.

Librarians can do more to support democracy than building gated islands of safe books that will be ignored by those who don’t already share the librarians’ opinions.

The library censor, who does have to decide if Martyr Made is safe for public consumption, accepts a more difficult task, and the challenge of figuring out in advance what can be safely shared tends to expand the scope of censorship. Those who assume responsibility for the virtue of their communities are inclined to be risk adverse, and it is better to be safe than sorry by excluding anything as soon as any critic calls it racist or antisemitic. And, if Carlson’s discussion with Cooper is not safe for libraries, what about the rest of their broadcasts and publications? If patrons find anything produced by Tucker Carlson in a public library, does that give him too much credibility as a legitimate thinker? Will unwary patrons believe that Carlson somehow has earned the library seal of approval and be more easily seduced by the potentially fascist evolution of his thought?

To me, such questions are unavoidable once librarians start down the path of censorship and represent an ever-expanding threat to the freedom to read, and Pearl’s admonition that we must overcome our own prejudices and be willing to share the most offensive of materials is unavoidable if we are committed to protect that freedom.

But, but, but … I know these views are controversial and suspect that some readers have been shaking their heads as they read the last few paragraphs.

“Yes, of course, intellectual freedom is important,” a critic might say “but, come on man, be reasonable. Some things are beyond the pale. Do you really have to distribute racist crap to support freedom of thought?”

Many believe that intellectual freedom is fully compatible with efforts to protect the public against lies and hate. Germany—currently a liberal society that allows the free expression of most political opinions—has anti-hate speech laws that prohibit denying or downplaying acts “committed under the rule of National Socialism … or approving of, glorifying or justifying National Socialist tyranny,”25 Most liberal democratic countries in Europe have similar laws. The United States, with our maximalist interpretation of the First Amendment that protects hate speech, is an outlier.

Amongst American librarians too, there has been spirited debate about what to do with Holocaust denialism. In 1984, while Pearl was working in Tulsa, David McCalden, an avowed Holocaust denier, tried to book a room at the California Library Association (CLA) convention in Los Angeles. Chaos ensued. At first, his reservation was cancelled. Then, when he threatened to sue, it was uncancelled. Then, when the LA City Council complained that they didn’t want to host McCalden in their city, it was cancelled again.

The controversy led to a vigorous debate at the 1988 ALA Convention, and a book of pro and con essays, The Freedom to Lie: A Debate about Democracy published in 1989. Both John Swan, who argued for tolerance of Holocaust denialism, and Noel Peattie, who argued against it, made passionate cases that persuaded many librarians (according to a post-debate vote at the convention, 76 agreed with Swan and 26 agreed with Peattie).26

Thus, I willingly acknowledge that this is a difficult question and that thoughtful, well-meaning, librarians will disagree, but I want to take a step back from the argument to make a more fundamental appeal to my colleagues. I want to say that at least the debate itself needs to be welcomed at an organization like the ALA and in the social world of librarianship. Consider the following statements.

Statement 1: “The atrocities committed by the Nazis against the Jews in World War II have been greatly exaggerated by mainstream historians to advance the propaganda goals of Israel and the United States.”

Statement 2: “Although statement 1 is morally and intellectually bankrupt, public library patrons should have the freedom to read books that argue in favor of statement 1.”

I’ve never met anyone who works in libraries who publicly agrees with Statement 1. Statement 2 has been hotly contested, but has been supported by serious free speech organizations such as the ACLU and by many long-time librarians such as Swan, Pearl (until June 2022), and myself. If American librarians truly are committed to intellectual freedom, Statement 2 cannot become unsayable at ALA conventions, and it cannot become morally unacceptable in library culture. But I believe that’s what happened in the Twitter response to Pearl’s comments.

John Wenzler is a librarian at Cal State East Bay.

Continue reading John Wenzler’s series for Freedom to Read Week, Nancy Pearl and Me: Reflections on the Changing Ethos of American Librarianship:

Part 2: Library Twitter's Push-Button Shushing Action (February 25, 2025)

Part 3: ALAlienation (February 27, 2025).

References

American Library Association. “Unite Against Book Bans.” Unite Against Book Bans. Accessed October 13, 2024. https://uniteagainstbookbans.org/.

Asheim, Lester. “Not Censorship But Selection.” Wilson Library Bulletin 28 (September 1953): 63–67. Available from: https://www.ala.org/advocacy/intfreedom/NotCensorshipButSelection.

Baltimore County Public Library’s Blue Ribbon Committee. Give ’Em What They Want! Managing the Public’s Library. Chicago: American Library Association, 1992.

Berry, John N. “Nancy Pearl: LJ’s 2011 Librarian of the Year.” Library Journal, January 16, 2011. https://www.libraryjournal.com/story/nancy-pearl-ljs-2011-librarian-of-the-year.

Carlson, Tucker. “Darryl Cooper May Be the Best and Most Honest Popular Historian in the United States. His Latest Project Is the Most Forbidden of All: Trying to Understand World War Two. (1:20) History of the Israel-Palestine Conflict (12:39) The Jonestown Cult (32:10) World War Two (45:04) How Https://T.Co/HJ2B8RjcCY.” Tweet. Twitter, September 2, 2024. https://x.com/TuckerCarlson/status/1830652074746409246.

Carnegie, Andrew. “Why Mr. Carnegie Founds Free Libraries.” Library Journal 25, no. 4 (April 1900): 177.

Clark, Karen Henry. Library Girl: How Nancy Pearl Became America’s Most Celebrated Librarian. Little Bigfoot, 2022.

Cooper, Darryl. My Response to the Mob, 2024. youtube.com/watch?v=JmvySzoLeo4.

Goldberger, David. “The Skokie Case: How I Came to Represent the Free Speech Rights of Nazis.” American Civil Liberties Union, March 2, 2020. https://www.aclu.org/issues/free-speech/skokie-case-how-i-came-represent-free-speech-rights-nazis.

Harris, Michael H. The Role of the Public Library in American Life: A Speculative Essay. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois, Graduate School of Library Science, 1975. Available from: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/items/4043.

Kirkpatrick, David D. “One City Reading One Book? Not If the City Is New York.” New York Times, May 10, 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/05/10/nyregion/one-city-reading-one-book-not-if-the-city-is-new-york.html.

“Legality of Holocaust Denial.” In Wikipedia, September 26, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Legality_of_Holocaust_denial&oldid=1247857438#By_country.

Mill, John Stuart. On Liberty. 1901st ed. New York: Walter Scott Publishing Co., Ltd, 1856.

“One City One Book.” In Wikipedia, March 7, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=One_City_One_Book&oldid=1212353604.

Pearl, Nancy. Book Lust: Recommended Reading for Every Mood, Moment, and Reason. Seattle, Wash. : [Berkeley, Calif.]: Sasquatch Books ; Distributed by Publishers Group West, 2003.

———. “Gave ’em What They Wanted.” Library Journal, Summer 1996.

Pearl, Nancy, and Craig Buthod. “Upgrading the ‘McLibrary.’” Library Journal 117, no. 17 (1992): 37–39.

Robertson, Katie. “Tucker Carlson Criticized for Hosting Holocaust Revisionist.” The New York Times, September 6, 2024, sec. Business. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/06/business/media/tucker-carlson-Holocaust-interview-biden-administration.html.

Streitfeld, David. “Amazon, Up in Flames.” New York Times: Bits Blog (blog), February 8, 2012. https://archive.nytimes.com/bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/08/amazon-up-in-flames/.

Swan, John, Noel Peattie, and Robert Franklin. The Freedom to Lie: A Debate about Democracy. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland, 1989.

Washington Jewish Museum. “Nancy Pearl: Washington Jewish Museum.” Accessed October 13, 2024. https://www.wsjhs.org/museum/people/nancy-pearl.html.

Wiegand, Wayne August. Part of Our Lives: A People’s History of the American Public Library. Oxford New York: Oxford University press, 2015.

Yorio, Kara. “With a Joyful Return to In-Person, ALA Annual Hosts a Censorship Discussion. A Twitter Controversy Ensued.” School Library Journal, July 1, 2022. https://www.slj.com/story/with-a-joyful-return-to-In-Person-ALA-annual-hosts-a-censorship-discussion-a-twitter-controversy-ensued.

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer-reviewed, all posts and comments must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, submit the Heterodoxy in the Stacks Guest Submission form in the format of a Microsoft Word document, PDF, or a Google Doc. Unless otherwise requested, posts will include the author’s name and the commenting feature will be on. We understand that sharing diverse viewpoints can be risky, both professionally and personally, so anonymous and pseudonymous posts are allowed.

Thank you for joining the conversation!

Mill, On Liberty, p. 41.

Clark, Library Girl.

Berry, “Nancy Pearl.”

Carnegie, “Why Mr. Carnegie Founds Free Libraries.”

See, for example, Harris, The Role of the Public Library in American Life: A Speculative Essay. Or Wiegand, Part of Our Lives.

Baltimore County Public Library’s Blue Ribbon Committee, Give ’Em What They Want! Managing the Public’s Library.

Pearl, Book Lust.

Pearl, 140.

Pearl, Book Lust, p. 4.

Pearl’s career overlapped with Robinson’s, and she engaged with his ideas. In 1996, she interviewed Robinson and his collaborator, Jean-Barry Molz, for Library Journal. See: Pearl, “Gave ’em What They Wanted.” In 1992, she described her approach to collection development at Tulsa City-County Library as an alternative to Robinson’s, see Pearl and Buthod, “Upgrading the ‘McLibrary.’”

Kirkpatrick, “One City Reading One Book? Not If the City Is New York.”

“One City One Book.”

“All Things Considered,” 9/1/2003, National Public Radio.

Washington Jewish Museum, “Nancy Pearl.”

Streitfeld, “Amazon, Up in Flames.”

Streitfeld.

American Library Association, “Unite Against Book Bans.”

Yorio, “With a Joyful Return to In-Person, ALA Annual Hosts a Censorship Discussion. A Twitter Controversy Ensued.”

Goldberger, “The Skokie Case.”

Berry, “Nancy Pearl.”

Asheim, “Not Censorship But Selection.”

Carlson, “Darryl Cooper May Be the Best and Most Honest Popular Historian in the United States. His Latest Project Is the Most Forbidden of All: Trying to Understand World War Two.”

Robertson, “Tucker Carlson Criticized for Hosting Holocaust Revisionist.”

My Response to the Mob.

“Legality of Holocaust Denial.”

Swan, Peattie, and Franklin, The Freedom to Lie, 5.

This is an excellent reflection, thank you! I particularly appreciate how you've set out the tension between our stated professional commitments to intellectual freedom and the moral imperative to protect the borrowing public from perceived misinformation. I look forward to the next installments!

Thank you, John, for this excellent post on the challenges for freedom of thought (and freedom to read) that have taken hold in the library field in recent years. The monoculture about certain topics that some in the profession have created results from lots of personally-created "Overton Windows" that add up to the monoculture--at least that's my hypothesis. Shrinking the "Overton Windows" about what's acceptable, and what's not, in a library collection, is a temptation for too many colleagues. And groupishness sets in, and cancellations of those who want to maintain open inquiry, results. Language policing and preference falsification are also collateral tendencies that result from the need to create conformity--and "purity tests" are now found too often, in a spiral of censoriouness.

I agree that books, or videos, or any other format, by authors I strongly disagree with (RFK Jr., or anything by the current spate of "influencers") should be available in order to promote counter-speech or "counter-reading."

I look forward to reading your next two articles. Thanks again!