Revelations

Hard to believe, but this month marks thirty years since outré stand-up comedian Bill Hicks died from cancer at the very unripe age of 32. I discovered Bill in the summer of 1994 when I was going on 15 years old. This would be the last summer I had those hours entirely to myself, as that fall and during subsequent summers my parents forced me strongly encouraged me to hold a part-time job. In that final halcyon summer of neither school nor work obligations, my main objective was videotaping as many syndicated Kids in the Hall episodes as possible, which meant I spent a solid portion of my days glued to Comedy Central.

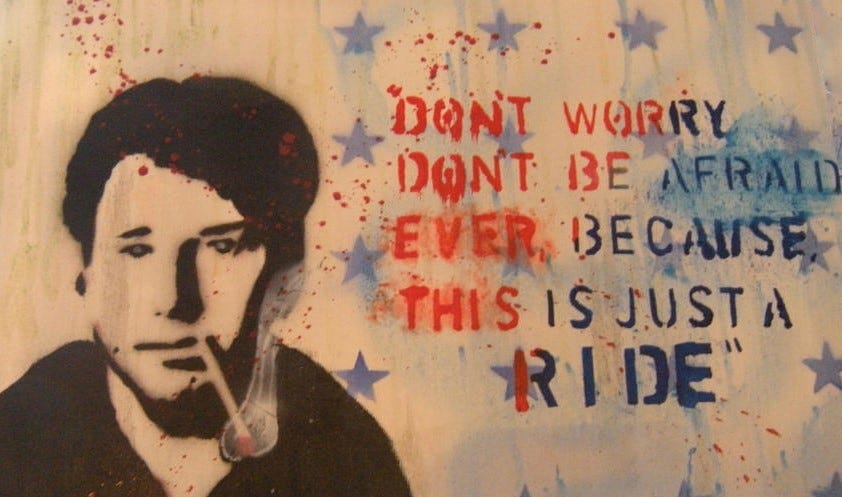

I was therefore ideally situated to encounter the Bill Hicks documentary It’s Just a Ride, produced in remarkably short order since Bill had only died a few months prior. In my assuredly imperfect memory, the documentary ran constantly that summer (although this contemporaneous article from Entertainment Weekly at least confirms the timing). I am not certain what compelled me to watch it at first, other than the fact that I enjoyed watching televised stand-up and I had never heard of him. The documentary featured entertainers I had heard of, and they all spoke of Bill Hicks with evident affection. Watching clips of his stand-up, I became mesmerized by this guy who had an air of Lenny Bruce about him: conversational, philosophical, and very much a scathing social critic. This guy with a firm stance against censorship, which appealed to me as a teenager who wanted to see R-rated movies in theaters and buy music with Parental Advisory labels. This performer with an apparent flair for the dramatic who had, among other things, filmed himself providing color commentary near the government standoff with the Branch Davidians in Waco. Who does that? Bill Hicks did! I have been an evangelist ever since. In the late 90s, I got my hands on CDs and VHS tapes of his sets. In college I would share them with friends, with the caveat that I didn’t endorse everything Bill said. Because most of the time, he was brilliant. Sometimes, he was uncomfortably goading. And occasionally, he was repulsive.

If you know you know, but in case you don’t: Bill’s comedy is not for everyone. He is often grouped with other high-octane “outlaw comedians” like Sam Kinison, which might in fact tell you all you need to know. Personally, I have never favored that automatic grouping of Bill with Sam Kinison. While it’s true that they both came from the Houston comedy scene, and Kinison played an influential role in Bill’s career, I find Sam Kinison’s delivery meaner and his material less interesting. That’s not to say Bill was significantly more accessible. His stand-up routines could be exceedingly crude. Some people watch comedy from an earlier period and remark “you couldn’t get away with saying that today.” People felt that way during Bill’s sets. His routines were instantly controversial. He liked pushing a joke as far as he could take it, either unconcerned that the audience was uncomfortable or perhaps delighting in it.

However, Bill’s comedy was not strictly shock comedy. Bill saw the comic as a truth-teller, and was committed to using comedy as a means of consciousness-raising. His sets were hilarious, exhilarating, inspiring, and satisfyingly provocative. He was as likely to extol the virtues of sex, drugs, and rock & roll as he was to rail against the military-industrial complex. I believe the first time I heard of Noam Chomsky was when I read that Bill had described his comedy as “Chomsky with dick jokes.”

Sane Man

A capsule biography for the uninitiated: Bill Hicks was born William Melvin Hicks in Georgia in December of 1961, the son of Southern Baptists. His earliest comedic influence was Woody Allen. He started performing in Houston comedy clubs when he was fourteen, before he would have been old enough to visit such clubs as an audience member (and the same age I was when I first heard of him). In early adulthood he moved to Los Angeles before returning to Houston, where he became part of a flourishing comedy scene. For the next decade he embarked on a grueling schedule, performing near constantly in venues around the world and occasionally appearing on television. After Bill was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer that had spread to the liver in June of 1993, he continued to perform between chemotherapy sessions, but the disease rapidly took its toll. In January of 1994 he moved to his parents’ home in Arkansas to die. On February 26, 1994, Bill departed for that great gig in the sky.

In his lifetime, Bill obtained a modest following. He enjoyed far greater popularity in the United Kingdom than he did in his native country. Bill saw it as a matter of scale: he had greater exposure in a smaller country with fewer television channels. Meanwhile in the United States, Bill’s intensity could clear rooms: according to fellow (controversial) comedians Louis CK and Joe Rogan, Bill regularly “bombed” in American comedy clubs. Well, the joke’s on us, my fellow Americans. Bill’s routines are perfection: each bit exquisitely timed, the sequences impeccably structured. His noticeable ad-libs — I’m thinking of the bit in Sane Man when the stool he’s humping falls apart — were incorporated seamlessly. His affectations ranged from wry understatement to incandescent rage, and he inhabited a lot of states in between.

So: what could have made Bill so polarizing to US audiences? I have described what his comedy was like in a general sense, and how special it is to me, but I have not addressed the substance of his jokes. When Bill described himself as “Chomsky with dick jokes” he was not exaggerating about the lewd content. Sexual acts were described and pantomimed in exacting detail; he acted out other bodily functions that are usually conducted in private. He had an unabashed yen for pornography, and how he talked about women could be rather disturbing. And bear in mind that Bill’s career overlapped with the Reagan and George H.W. Bush years, the rise of the Moral Majority, and Jesse Helms’ crusade against the National Endowment of the Arts. Bill himself once observed that his thumb was not on the pulse of America.

As for the Chomsky allusion: I grant that Manufacturing Consent might not be the most obvious source for stand-up material, but Bill made it work. He saw commercial mass media as the handmaiden of the political establishment and was prone to referencing the television series American Gladiators, cable news, and commercials as embodying the worst of American cultural production. He was extremely cynical about US politics and the stated versus genuine aims of American foreign policy. He excoriated the Republican Party and the religious right, though he did not spare the Democrats. And he didn’t lambast elites or tell suggestive jokes; he often did both simultaneously. Unsurprisingly, he joked about smoking and cancer, and how smoking would eventually kill him — oh man does that punchline sting.

A core component of the Bill Hicks experience wasn’t just what he said, but how he said it. Bill’s delivery could be really intense. Like… really, really intense. He would literally scream at the top of his lungs while telling a “joke.” In one infamous instance, he confronted a drunken heckler before proceeding to berate the entire audience. Bill’s contemporaries — including Joe Rogan and Louis CK, but also Brett Butler, Jay Leno, and Thea Vidale — alleged that Bill was too uncompromising to appeal to a larger audience. He didn’t care if he scared people or alienated them, because he valued authenticity more than being famous. They express obvious admiration for this commitment to integrity while also seeing it as his albatross. I never knew the man personally, so I concede that we should defer to those who actually worked with him. But whether Bill was gagging, humping, or screaming, I think he knew what he was doing. It was all part of the act.

Inevitably, decades-old entertainment will seem dated in various ways. Bill’s JFK assassination fixation and his Jim Fixx jokes are of a particular cultural moment. Yet watching some of Bill’s stand-up can still feel prescient, especially when it comes to his critiques of inexorable commodification and consumerism. He quipped that USA stood for “United States of Advertising,” and proclaimed that any performer who made a commercial had severed any further claim to artistry (Willie Nelson was his sole exception). He otherwise indicted television programming for playing to the baser aspects of human nature by prioritizing cheap entertainment over thoughtful engagement. In turn, an entertainment-obsessed culture seeks a constant flow of fleeting stimuli at the expense of nurturing deeper relationships with ourselves and one another. The more we prioritize stuff and convenience, and conversely, the less we prioritize substance and focus, the more our connection to our individual and shared humanity dissipates. Not just our shared humanity — Bill talked about a shared consciousness. Between that and his antipathy to television, he could have just as well christened himself Carl Jung or Neil Postman with dick jokes.

Thirty years later, our lives seem more fueled by stuff than ever, while people report feeling lonelier. Human beings refer to themselves as “brands.” Bill died before the age of prestige television, but even if he had lived to see The Wire or Breaking Bad I doubt that would have done much to change his mind about the numbing quality of screens. Writing to New Yorker staff writer John Lahr in 1993, Bill described television as “bad drugs that deaden the mind and drive a wedge between our conscious and unconscious minds, and between ourselves and each other, and between us and them, and between us and the experience of Life itself.” Bill certainly wasn’t right about everything, but on some issues he was exactly correct.

Relentless

So, Bill was exceptionally funny, and yet he wouldn’t play nice. He filmed some comedy specials and had appeared on network television, which means he had some decent exposure, but he still hadn’t fully made it as a professional comedian. In the It’s Just a Ride documentary, Jay Leno said Bill was always too intense for The Tonight Show, though he appeared on Letterman eleven times without incident (Leno was reportedly trying to book Bill shortly before he died). However, his twelfth and final performance on Letterman didn’t air in October 1993. Bill was censored by CBS after being informed he had run afoul of its Standards and Practices, even though the routine had been approved in advance by Letterman’s people. His routine on the prudishness of “pro-life people” was deemed too offensive to air, and another comedian’s act was substituted where Bill’s should have run. Not since Elvis the Pelvis gyrated on stage in 1957 had a performer been censored at the Ed Sullivan Theatre. According to his own and other contemporary accounts, Bill was perplexed by this decision. He did not seem angry so much as distressed and confused.

And here we finally arrive at why I wanted to write about Bill Hicks for Heterodoxy in the Stacks on the thirtieth anniversary of his death: he espoused a broad and principled commitment to free thought and expression that warrants commemoration. Bill elaborated on his anguish over being censored by CBS in an impassioned 32-page letter1 to John Lahr. He saw it as kowtowing to interest groups and an insult to the intelligence of the American public. Bill thought viewers should get to judge his content for themselves, not the network. He couldn’t get a direct explanation of who made the call to censor him or why. But he acknowledged that the incident had proved a boon for his career: Bill’s people loved him, and they were pissed. He was getting exposure like he never had before in the United States. Meanwhile, Lahr wrote a profile on Bill that appeared in the New Yorker shortly after the censorship incident. The response was marvelously supportive, and Bill seemed on the verge of greater recognition. We will never know, though, since he died just four months later.

Like his hero Jimi Hendrix, that Bill died so young has served in part to cement his legendary status. One of the best things about being a Bill Hicks obsessive is meeting fellow goat children in the wild. When I lived in Austin in 2001, seeing a Bill Hicks section at I Luv Video made me feel right at home. My most memorable Bill-related encounter occurred, I am very pleased to say, at an ALA Annual roughly twenty years ago. Soft Skull Press had a booth in the exhibits hall, and they had recently published a Bill Hicks-related title. A man staffing the booth shared that in celebration of the book’s publication, they had also produced a limited run of black rubber wristbands that read WHAT WOUD BILL HICKS SAY. That “woud” is not a typo – there was a character limit, so a misspelling was unavoidable. Regardless, this is without question the best swag I have ever scored at an ALA conference.

At the same time, I’m well aware some people really don’t understand the hype, and some downright loathe Bill Hicks. A Vice reappraisal from 2012 finds Bill’s material sophomoric and his delivery “unbearably smug.” A 2013 review on IMDB titled “most overrated stand-up comic” concludes that Bill was “nothing but a flash in the pan.” A Guardian piece from 2019 asked younger comics to assess Bill, and they were similarly unimpressed. He’s an angry white guy, an abrasive misogynist who punches down. One comedian told the Graun “We don’t need to say ‘anything we want’. You can dismantle things without being offensive.” I can appreciate where these critics are coming from. Like removing a monument from a public square, they’re saying it’s time we stopped lionizing past comedic greats out of habit, such as Bill. The reasons why he was lauded when he was alive no longer apply, or maybe he should have never been lauded in the first place. We detract from other more worthy voices.

That being said: when it comes to assessing for offense, I don’t know that it’s entirely fair to compare certain Bill Hicks routines — preserved in amber, never changing — to conventional mores. Some of the most shocking content of previous decades simply does not get as much traction today. For example, you won’t see Eddie Murphy or the Diceman making AIDS jokes anymore. Had Bill lived, it stands to reason that some of his cruder material would have evolved as well.

The other thing is, I am untroubled by claims that some of Bill’s jokes haven’t aged well. That his jokes were meant to provoke was blindingly obvious at the time. He was often at his most inspired when going to extremes. I freely admit that some of his stuff was uncomfortable for me to watch thirty years ago, and it is not better now. But the routines that make me squirm are relatively few in proportion to the ones I find hilarious and moving. Bill asserted many times that he had no interest in pursuing universal appeal, because there is no such thing. He knew that saying what we really think might not make us popular; however, he also believed that it is only in being honest that we can establish trust and genuine connection.

Of course, whether someone appreciates Bill’s stand-up might come down to a matter of taste, which is subjective. I wouldn’t expect everyone to share my tastes in film or literature, and the same goes for humor. That being said, I think that Bill deserves to be remembered not only for his stand-up, but what he stood for. So even for those who are turned off by Bill’s work, I hope they can at least appreciate his bravery. Someone Bill admired very much, Noam Chomsky, once suggested “we shouldn't be looking for heroes, we should be looking for good ideas.” I remain grateful to Bill for how he modeled pointed criticism: of mass media, of political systems, of authoritarianism. And ultimately, I think Bill’s greatest contribution is how he modeled a commitment to freedom of expression and anti-censorship. When asked if he was concerned about offending people, Bill would say that reasonable adults have two options when they don’t like what someone says: ignore it or respond to the idea. What they shouldn’t be able to do is silence the speaker. I assume Bill would have agreed with Lester Asheim; that in a democratic society, we should approach ideas from the position of selectors rather than censors.

We might be tempted to dismiss the censorious as ignorant or irrational, but I would venture that censors generally do not view themselves that way. The most zealous censors tend to think they see things very clearly, and their cause most worthy. Censors know unequivocally which ideas are so threatening they should never be uttered anywhere; certainly not presented in a tangible format such as a book or permitted to be discussed in a public venue. In contrast, the selector would counter that the better way to confront controversial ideas is to engage them head on. Because if you truly believe your arguments are the ones on which to build a free and just society, then you should have every confidence that your superior ideas will triumph over the ones you oppose. There can be no real contest of ideas, though, unless it is out in the open.

Now, I realize that to some, this position sounds dangerously, stupidly naive. There are some really scary ideas. The ideas that tend to disturb us the most are the ones that seem to deny, or in fact deny, human dignity. Furthermore, not every venue is conducive to the nuanced presentation of sensitive topics. But there are information institutions that ostensibly exist to serve that very function. Libraries and the news media are supposed to help us make sense of controversial ideas, not deliberately suppress them. When these institutions act as censors, they fail in their obligations to the public. Bill Hicks is worth remembering if only to remind us that censorship is inherently antithetical to any society that would call itself free or just.

It’s Just a Ride

Bill Hicks has now been dead for almost as long as he was alive. After just 32 years on this planet — fewer than another of his heroes, Jesus — he left an influential legacy that continues to resonate today. Why? In his electrifying stand-up routines, he tackled the most urgent, existential topics while being mordantly funny. And thanks to the preservation of his limited yet rich body of work, the ardor Bill inspired during his brief life has only multiplied. He has achieved immortality of a sort.

While I have made reference to some of Bill’s material, I have refrained from directly linking to any of his stand-up. If you are curious about Bill’s work, I encourage you to watch or listen to a proper set or curated collection, not just some random, out-of-context clip. For a video experience, I recommend Relentless — if you dare! And while you definitely miss something without the visual, audio recordings are still a great introduction; for that I would go with Rant in E-Minor. Bill’s mind could go to some dark and twisted places. Maybe you’ll laugh, maybe you won’t. Remember: it’s just a ride.

Bill Hicks, dying of cancer, closed his epic letter to John Lahr stating a hope that “I’ll see you all in Heaven, where we can really share a great laugh together, forever and ever, and ever.” Bill, I don’t know that there’s an afterlife. But if there is, I like to imagine you’re out there somewhere trading stories with Yul Brynner, having a blast; your third eye fully squeegeed and wide open. And I trust that wherever truth, love, and laughter abide, you are indeed there in spirit.

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer- or editorially-reviewed, all posts must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, send an email with the article title, author name, and article document to hxlibsstack@gmail.com. Unless otherwise requested, the commenting feature will be on. Thank you for joining the conversation!

References and Further Reading

Jack Boulware, “Too Close to the Bone: Bill Hicks’ Biting Routine Kept Him a Cult Comedian,” SFGate, December 26, 2004.

Noam Chomsky, Interview by David Cogswell, September 14, 1993.

Michael Corcoran, “God Wept: The Bill Hicks Story,” Overserved, October 23, 2021.

Rupert Edwards, It’s Just a Ride, Tiger Television Productions, 1994.

Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, New York: Pantheon Books, 1988.

Bill Hicks, Love All the People: The Essential Bill Hicks, New York: Soft Skull Press, 2008.

⸻, Rant in E-Minor, Rykodisc, 1997.

⸻, Relentless, Tiger Aspect Productions, 1992.

⸻, Revelations, Tiger Aspect Productions, 1993.

⸻, Sane Man, Sacred Cow Productions, 1989.

John Lahr, “The Goat Boy Rises,” The New Yorker, November 1, 1993.

⸻, “My Correspondence with Bill Hicks,” The New Yorker, April 1, 2011.

Richard Lewis, “The Day I Met Bill Hicks…Then Saw His Insane Show,” Chortle, April 18, 2017.

Brian Logan, “‘Bill Hicks Was a Bit Misogynist’ – Young Comics Reassess the Standup Legend,” The Guardian, February 24, 2019.

Paul MacInnes, “Bill Hicks: Do the Legendary Comic’s Jokes Still Stand Up?” The Guardian, November 26, 2015.

Paul Outhwaite, “Bill Hicks Bio.”

Harvey Pekar, “A Tale of Two Comics,” Austin Chronicle, March 21, 1997.

powerbob1760, “Review of Bill Hicks: Relentless,” April 21, 2013.

Oscar Rickett, “Shut Up About Bill Hicks,” Vice, August 6, 2012.

Joe Rogan and Louis CK, “Joe and Louis Talk Bill Hicks and Steve Martin,” Joe Rogan Experience 1929, original airdate January 26, 2023.

Robert Seidenberg, “The Life of Bill Hicks,” Entertainment Weekly, June 3, 1994.

Dan Solomon, “The Conspiracy Theory That Alex Jones is Actually Legendary, Long-Dead Texas Comedian Bill Hicks,” Texas Monthly, November 25, 2014.

Joe Sommerlad, “Remembering Legendary Stand-Up Comedian Bill Hicks 25 Years After His Death,” The Independent, February 26, 2019.

Cynthia True, American Scream: The Bill Hicks Story, New York: Harper, 2002.

Rick VanderKnyff, “Comic Irate at CBS’ Cutting His Spot on Letterman Show,” Los Angeles Times, October 8, 1993.

Peter Watts, “A Brit on the Side: Why American Comic Bill Hicks Felt Most at Home in the UK,” The Independent, April 25, 2010.

Bill Hicks’ letter to John Lahr, of which I’ve read the transcribed version, has been reported as having been 31, 32, or 40 pages. I selected the middle option.

Fun fact-- Bill Hicks graduated from my high school, albeit years before me. I didn't discover him until around 2004 though-- you were way ahead of me! I often think of his joke about how people who work in PR should just "kill themselves" and how he would probably say that about journalists today.

I was also living in Austin in 2001, managing the Oak Springs Branch Library. Maybe we crossed paths in I Luv Video.