Wicked Problems and Comprehensive Doctrines: Interventionism and Social License in Librarianship

On the inappropriateness -- and hazards -- of positioning library workers as "radical change agents" in a world of complex problems for which we've been granted no public warrant to address.

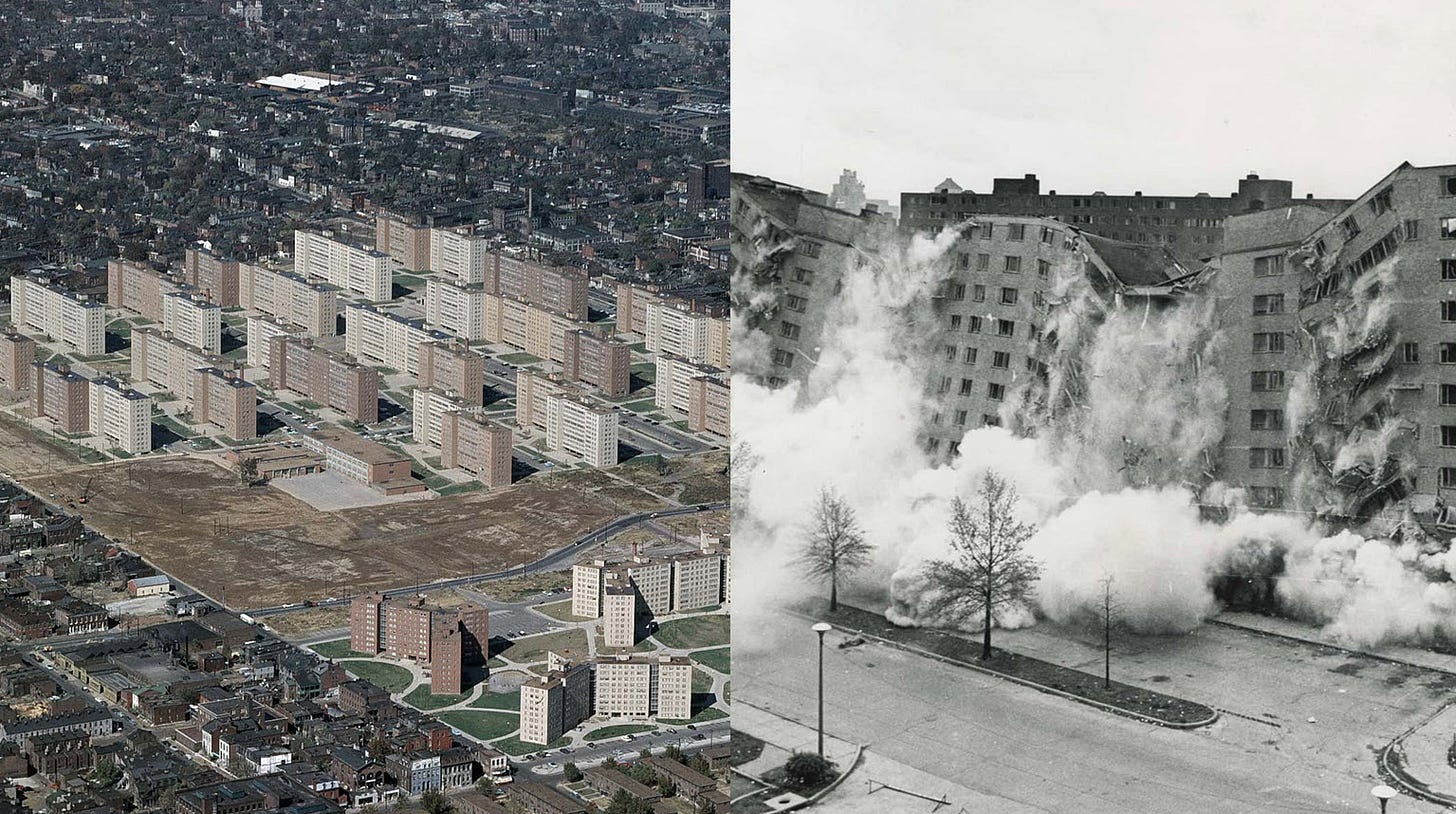

[Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis, Missouri and its demolition in 1972; images in the public domain]

(Keynote presentation to the first Summit of The Association of Library Professionals, or ALP, August 8th, 2024).

Introduction

First I’d like to thank the Summit organizing committee for inviting me to present this keynote. It’s a rare and significant honor to be given the opportunity to offer words of—hopefully!—insight and inspiration to launch an inaugural event for a newly-formed organization. Welcome to the first Summit of the Association of Library Professionals! As we all know, ALP is, itself, a unique and potent opportunity to offer an alternative vision for our profession, a profession which we all care so deeply about.

Yet what we aspire to with ALP—what we espouse, what we as professionals profess—isn’t really at its core an alternative vision for the library profession at all so much as it is—as our Summit theme declares—a renewal of the heart of librarianship, which is to say reclaiming, defending and reinvigorating the principles of institutional neutrality, intellectual freedom, freedom of speech, freedom of expression and freedom of thought—and the vital role of the publicly-funded library in supporting all of these freedoms. We seek to be intentionally neutral and non-partisan in a society that has become sharply polarized in countless ways, in the hope that, by creating and nurturing a venue for viewpoint diversity for all the stakeholders in our communities, we can—alongside other (small l) liberal institutions--play a role in helping democracies to thrive.

And please note my words: play a role in. Not shape. Not guide. Not lead. Not socially engineer or intervene in.

That such a reclaiming on behalf of the library professions should ever have become necessary is indeed remarkable. Those of you who have worked in the field for a decade or more may have operated almost your entire working lives under the assumption that these principles were the heart, the purpose, the telos (or end goal) of librarianship. I graduated from library school in 1993 and it took me (regretfully) until 2019 to discover (somewhat painfully) that these principles were no longer universally-shared among all of my colleagues, and that librarianship is facing not just a crisis of confidence in its own principles and purpose, but an active, ideological struggle over its future.

My intention for this keynote is to relate how I came to understand what was happening to librarianship and what is at stake, and how I drew on theories and concepts from another discipline entirely—city planning—to both reinvigorate my own practice and to contribute to charting a path to renewing the heart of the profession.

The Interventionist Turn in Librarianship

In addition to my MLIS I hold a master's degree in city planning. I entered the program at the University of Manitoba in 1998, after nearly 10 years working in public libraries and completing my MLIS degree in 1993. At the time, I was particularly engaged in sustainable transportation issues as well as the study of urban history. I found planning to be a fascinating field, as it involved examining theories of society and social change, and the professional ethics involved in turning knowledge into action in ways that can affect people and communities for years and decades into the future. I remember thinking, how did I get by this far in life and not know about these ideas—some of which, I thought, could easily have been included in library school?

But I now realize that planning also afforded me a particular insight into the ways in which librarianship has been losing its way.

The first sign of trouble for me came in late 2019, when the debate over gender identity ideology—the idealistic notion that one’s metaphysical sense of gender trumps biological reality—began to erupt in Canada with speaking events in public library meeting rooms by gender critical feminist Meghan Murphy, (of the Feminist Current website) who argued that these beliefs were having very real and harmful impacts on the privacy, safety and dignity of women and girls. In the fall of that year, Vancouver Public Library was embroiled in controversy over its decision to book Murphy for the following January, while Toronto Public Library, in the face of intense opposition from activists, went ahead with Murphy’s talk that October, thanks to the principled stand of City Librarian Vickery Bowles, but which drew hundreds of chanting protesters. A similar scene would take place at the Seattle Public Library in January 2020. From what I was seeing in the professional literature and on social media, many librarians were among those opposed to the events, arguing that they were “harmful,” the speaker a bigoted “TERF” (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist) and that anyone who would want to attend must be motivated by “hate.”

But my “inner city planner” was setting off alarm bells. Here were public events attracting large crowds of (mostly) women to discuss a matter of public interest—to assert their right to safely access the public realm in the form of washrooms, swimming pool locker rooms and public showers, without encountering males (however they identify). These women were, by any conventional measure, legitimate stakeholders who were fully entitled to organize and attend events in public library meeting rooms and exercise their rights to freedom of speech and assembly. I recognized that no city planner would dream of disallowing such an event, or denying these stakeholders the right to attend it, as so many librarians were arguing; and that public libraries had a duty to allow this issue a hearing. My efforts to raise awareness to this effect on my (now defunct) personal blog were viewed as—let’s just say—controversial, but that’s a topic for another day.

The more I looked into this issue, the more I realized there was something even more troubling going on: that librarianship had become nakedly interventionist, with open calls in the literature for library workers to intervene in society—and even within the minds of our patrons—in order to address social problems and shape the world in a very particular ideological direction.

Let's look at some examples.

2005: Todd Honma, in his article “Trippin’ Over the Color Line” argues for an “ethnic studies” approach to LIS education, one focused on social justice, “in order to usher in a truly transformative LIS—one that transforms itself and the world.”

2011: R. David Lankes published his encyclopedic work The Atlas of New Librarianship, the central tenet of which was his exhortation that the purpose of librarianship was to “improve society,” to “change the community and society for the better;” to “bring about change;” and that to do so, librarians needed to take the lead on “improv[ing] society through action,” as “radical change agents,” which would require that librarians learn “how to plot and scheme, cajole and convince. How to map power and gain power to put behind a vision…” As such, “Library school should be [] a caldron and training ground for activists and radicals.”

2020: An article by E.E. Lawrence in the Journal of Documentation entitled “On the problem of oppressive tastes in the public library” argued that library workers have an obligation to intervene to “modify” readers’ “oppressive tastes” which “work[] to maintain unjust power relations.” This, in the author’s view, justified “maximizing the principle of social justice while minimally diminishing the principle of autonomy” through “nominally” coercive means.

2021: The “New Librarianship Symposia” at Columbia University included a paper by M.H. Mathiasson entitled “Working for a better world: the librarian as a change agent, an activist and a social entrepreneur,” the latter of which is defined in the literature as “a catalyst for social transformation (…) that creates innovative solutions to immediate social problems and mobilizes the ideas, capacities, resources, and social arrangements required for sustainable social transformation.”

2021: ALA introduces a new principle to its Code of Ethics, ethic #9:

We affirm the inherent dignity and rights of every person. We work to recognize and dismantle systemic and individual biases; to confront inequity and oppression; to enhance diversity and inclusion; and to advance racial and social justice in our libraries, communities, profession, and associations through awareness, advocacy, education, collaboration, services, and allocation of resources and spaces.

(I’ll come back to this statement later).

2021: At the ALA Midwinter conference, ALA adopts the “Resolution to Condemn White Supremacy as Antithetical to Library Work,” which starts off with the assertion, “Whereas libraries have upheld and encouraged white supremacy both actively through discriminatory practices and passively through a misplaced emphasis on neutrality,” before declaring that librarians “must reject practices, movements and groups that oppose equity, diversity and inclusion.”

2022: ALA’s Working Group on Intellectual Freedom and Social Justice submits its final report on alternative language to neutrality, proposing “that radical empathy would be an effective way to achieve the goal of a more equitable and inclusive future.”

For good measure, the website for Critical librarianship (#CritLib) states: “Recognizing that we all work under regimes of white supremacy, capitalism, and a range of structural inequalities, how can our work as librarians intervene in and disrupt those systems?”

I’ve written previously at Heterodoxy in the Stacks that I believe that many librarians have – for all their good intentions – fallen into what sociologist Ilana Redstone calls the “Certainty Trap”, or the “resolute unwillingness to recognize the possibility that we may not be right in our beliefs and claims” and that “there’s more than one way to see a given issue.” As a result, those under its sway are invariably led to believe that if people disagree with them, it can only be because of “ignorance or hateful motives.”

But what is more, the passages I’ve offered here point to something else: a profession that is claiming for itself the right—indeed the obligation, the duty—to intervene in society to address “immediate social problems” and work towards “social transformation” through “nominally” coercive means.

This interventionism is not occurring in a vacuum, nor did it arise wholly internally in the LIS literature. It is deeply informed by the work of Brazilian Marxist educator Paulo Freire, whose 1970 book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed is key to notions of critical pedagogy, and (in LIS) critical information literacy. In the book, Freire declares that teachers need to help students “develop the critical consciousness which [will] result from their intervention in the world as transformers of that world.” ? This model and its revolutionary, transformative relationship between teacher and student has been eagerly adapted in LIS: A search in Google scholar for librarianship and Freire yields more than 22,000 hits.

But transforming the world by addressing broader social problems is not nor has it ever been the domain of librarianship—outside of the realms of promoting literacy and assisting in the social integration of immigrants. Rather, this imperative is the purview of city planning, a profession oriented to the principles, techniques, and, most importantly, ethics involved in trying to first understand the nature of social problems in order to implement—and then evaluate—potential solutions. To fully appreciate the inappropriateness of these interventionist aspirations on the part of librarianship requires understanding the vital distinction we must make between wicked problems on the one hand, and comprehensive doctrines on the other.

Wicked Problems and Comprehensive Doctrines

In their classic 1973 paper, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” authors Horst W. J. Rittel & Melvin M. Webber first introduced the idea of “wicked problems,” or those highly complex social policy issues faced by pluralist societies for which no clear definition, solution or test is known to exist, such as urban planning issues and changes to public education curricula. Each problem they argued may be a symptom of still another problem. This article, which appeared in the pages of the journal Policy Sciences—has been cited in excess of 25,000 times. To call a problem “wicked” isn’t to say that the problem is bad, only that resolving it to everyone’s satisfaction in a pluralist, democratic society is not only difficult but impossible because of the “differentiation of values that accompanies differentiation of publics,” (156) such that a “plurality of objectives held by pluralities of politics makes it impossible to pursue unitary aims” (160) or a unitary conception of the “public good”.

In other words, in a diverse society, there will be—as American philosopher John Rawls put it in his 1993 book Political Liberalism—many different “conceptions of the good” such that single, universal “comprehensive doctrines” can never satisfy all such conceptions and so must not, in a liberal society, be imposed. In a politically liberal society, Rawls wrote, groups of people are entitled to their own comprehensive doctrines which they believe to be true—comprising as they do religious faith or metaphysical beliefs and corresponding guidance concerning morality and proper social conduct—but these so-called “thick” theories cannot be imposed on others. (This is the essence of the “Establishment Clause” in the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits the establishment of a state religion: freedom for religion is only made possible by freedom from one particular religion, as well as freedom from state interference in one’s faith). Instead, Rawls argued, we are guided by our “thin” theories of political liberalism on which all can agree, such as individual liberty, freedom of speech and expression and so on, all of which allow diverse groups to share society together.

As such, public decision-making in a politically liberal and pluralist democracy is only made possible through an emphasis on the processes (“thin” theories) that aid us in seeking an overlapping consensus regarding public problems—problems which are often wicked in nature, originating as they do in multiple causes and therefore definable in many different ways depending on the values of the diverse stakeholder groups involved.

The complexities of wicked problems, and the ethical concerns inherent in contemplating any intervention in society, were core to our education in city planning, which not, incidentally, has its own literature concerning the debate over practitioner neutrality. Following decades of theorizing, the planning profession has acknowledged that objectively value-free interventions are not possible, but that the ethical practitioner can act as a facilitator and mediator between conflicting stakeholder values, while striving not to impose their own. We also learned that information is always going to be incomplete, the consequences of interventions can’t be foreseen, and as the “change agent” the planner is ultimately responsible for those consequences and thus has “no right to be wrong.” We were taught to take this responsibility very seriously because of the many instances when planners did get things wrong, with unfortunate consequences for the lives of city dwellers.

Perhaps the most notorious such example was the massive, 33-tower Pruitt-Igoe public housing development in St. Louis, Missouri that had to be dynamited in 1972, 17 years after it was built, because the development proved unlivable for its residents. The assumptions that went into its planning could not survive contact with reality.

Yet, proponents of critical librarianship are seemingly insensible to these cautions regarding the wickedness of social problems as well as to the limits of their own expertise, and have instead adopted a number of comprehensive doctrines concerning race and gender which they seek to impose on library users and society—coercively, if need be.

But one cannot understand—much less solve—a wicked problem by means of a comprehensive doctrine. Homelessness, for example, is a wicked problem. Planners and policymakers seeking to understand and address it must consider a host of complex, interrelated factors, such as local economic conditions, housing markets, the policy environment, and the unfortunate role played by addictions and mental health conditions. By contrast, viewing the problem strictly through the lens of the comprehensive doctrine that is Critical Social Justice would bypass these complexities entirely to instead see participants not as individuals but in terms of their immutable group identities and as either oppressors or the oppressed—all of whom must engage in the ongoing and endless process of gaining a critical consciousness—and that any disparity of outcomes in society is caused by power-laden oppressive systems which must be challenged and disrupted.

As well, the intergenerational legacy of segregation, Jim Crow laws and racist restrictive covenants during the early-to-mid 20th Century that prevented black families from acquiring property and passing this wealth down to their descendants is another wicked and persistent socio-economic problem. Critical Race Theory on the other hand is a comprehensive doctrine of activist scholarship sees racism as an ordinary and permanent part of society and inherent in virtually all social interactions and institutions, and which, according to Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic (in their book Critical Race Theory: An Introduction), “questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law” (p.3). In other words, CRT questions those very “thin” theories so essential to discussing and debating how best to address that wicked problem.

Applying a comprehensive doctrine as a solution to social problems means that one is assuming causes and effects, and dispensing with any inquiry or evidence-gathering whatsoever. That this is an inappropriate way to approach problems in the public domain appears to have completely escaped our colleagues dedicated to social justice and transforming the world through librarianship. It has led, ironically, to an inversion of professional commitments: From a conviction that freedom of information and the exercise of intellectual freedom support the pursuit of social progress, to a conviction that a particular socio-political order (Social Justice) must be established and enforced by excluding contrary information and opposing views.

How do we untangle this, and return to first principles? First, we need a renewed understanding of the source and nature of our professional values.

Defining the Telos of the Public Library

Before we consider our institutional values, we need to review a foundational understanding of the library’s Telos as public institution. By Telos we are referring to the ultimate purpose of the institution, the desired end state in society towards which that institution works.

Jonathan Rauch, in his 2021 book The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defense of Truth, examines the four institutions on which he argues the construction of knowledge in democratic societies depends: Government, the legal system, journalism, and the academy— the integrity of which depends for each on long-standing shared practices of information gathering and evaluation for evidence based decision making, which make them (ideally) the foundations of the ”reality-based” community.

Let’s look at the telos of each:

Government:

Telos: A functioning and stable society (ensuring fair adherence to transparent rules of coexistence; addressing socio-economic problems through policy [i.e., the planning function])

Legal system:

Telos: A deliberative and just society (ensuring processes for conflict resolution and safe coexistence in practice)

Journalism:

Telos: An informed and politically engaged society (ensuring transparency about the other branches of the CoK)

The Academy:

Telos: An educated and inquisitive society (engaged in the search for truth)

Regretfully (and surprisingly) Rauch didn't include libraries among these institutions, but following his argument we could naturally situate them this way:

Libraries:

Telos: A knowledgeable and literate society (engaged in pursuing individual intellectual and recreational fulfillment; provides equal access to all public content concerning the other branches.)

Note that all of these institutions are premised on process, principles, professionalism and ethical guidelines – not specific ideological and moral content or prescribed sociopolitical outcomes. And a Telos or the ideal end state is something towards which we work in an incremental and iterative fashion but we can never say has actually been achieved: Accordingly, governments work towards a stable and functioning society, and the justice system works for a just and fair society but that it's not something that will ever be finalized. That's where Critical social justice parts ways: It demands and expects to achieve racial and social justice.

By contrast, the search for a knowledgeable and literate society as a telos would be our foundational “thick” theory. In advancing this Telos we are not being value-neutral, nor should we be. There is absolutely no ethical problem in promoting this comprehensive doctrine, and exercising our institutional capacities towards this end. That's because this doctrine is content-free: it makes no assumption regarding the content of that knowledge, or the nature or quality of the literature enjoyed by members of that literate society. The same is true of the other “branches”: their respective teloi do not depend on specifically-defined content. Democratic government can take the form of a republic or a constitutional monarchy; the content of laws varies according to jurisdictions and their legal traditions; journalists are supposed to strive for objectivity but news outlets can be biased across the political spectrum and adopt a focus particular to each publication; each academic institution sets its own curriculum.

This is where our “thin” theories of the good come into play, and are essential for our success: institutional neutrality as regards to content thereby grants users the intellectual freedom to explore that content, and the autonomy to reach their own conclusions about it.

Social License and The Public Interest

Building on Rittel and Webber, there is also an important distinction to be made here between the public good and the public interest. If you think the library is supposed to promote the public good, that might compel you to decide arbitrarily what that “good” is, and deliberately avoid purchasing a controversial title in the belief it would harm certain members of your community; on the other hand, a belief in the library’s role in serving the public interest is a compelling justification to include that title so as to inform reasoned debate, regardless of the offense it might cause.

The other relevant convention here is the idea of social license, which may be defined as “an informal contract between public or private organizations or the government that begins with public acceptance and must be sustained based on communities’ trust in the legitimacy, credibility, effectiveness, and fairness” of that institution and its activities.1 Based on legal conventions, the existence of professional accreditation, and government mandates, city planners have the social license to take the lead in shaping the built environment, transportation infrastructure, and social policy changes. For all the same reasons, librarians have the social license to develop, organize, and manage collections of print and digital materials and other media, and to make them available to the public.

It is therefore, very simply, a violation of that social license granted to us by society for library workers to appropriate the "constitutional" powers of these other "branches" and to intervene in society to shape it according to their own assumptions. At no point have the library professions been granted the social license to transform society, nor is there anything in our LIS education to prepare us to do such things by encouraging an understanding the wickedness of public policy problems, or the ethical implications inherent in any attempt to address these problems. For librarians to assert otherwise is to display an astonishing level of hubris. Critical librarians presume to know the causes of social problems, the sources of oppression, the identity of the oppressors and the oppressed, and seem to care not at all about the extent to which their preferred actions informed by their devoutly-held comprehensive doctrines are even compatible with democracy.

What, then, is the ethically-appropriate stance for the publicly-funded library as regards its values in pluralist, democratic societies? As John Wright and I argued in our 2022 paper, the pathway most consistent with democracy is Multidimensional Library Neutrality.

The Thin Theory of Librarianship: Multidimensional Library Neutrality

Bearing in mind the telos that the library works towards (a knowledgeable and literate society), library neutrality should not be understood as an ontology—a statement about what exists—but rather as an ethical commitment to engaging with members of the public in a manner that articulates:

1. Value neutrality: Being careful not to impose one’s “comprehensive doctrines” on library users through collections, programs, or spaces; or those held by any other stakeholder group on the whole community.

2. Stakeholder neutrality: Granting all community stakeholders equal access to the library’s resources, removing where necessary barriers to access for some users.

3. Process neutrality: Developing transparent policies regarding access and use of collections and spaces and applying them equally and fairly to all community stakeholders.

4. Goal neutrality: Granting library users autonomy to use the library for their own purposes, and not imposing on them one’s own preferred goals.

What’s important to keep in mind is that these elements are not discrete and mutually exclusive: Rather, they are all mutually reinforcing, none can exist without the other. Stakeholders holding their own “thick” theories and dedicated to pursuing their own goals can only be accommodated in libraries by “thin” institutional principles of value- and process neutrality. Stakeholders are only able to achieve their goals because the library doesn’t interfere with those goals or seek to replace them through nominally coercive means.

What does this approach to neutrality look like in a policy context? Let’s reexamine ALA’s 2021 Code of Ethic #9:

We affirm the inherent dignity and rights of every person. We work to recognize and dismantle systemic and individual biases; to confront inequity and oppression; to enhance diversity and inclusion; and to advance racial and social justice in our libraries, communities, profession, and associations through awareness, advocacy, education, collaboration, services, and allocation of resources and spaces.

There are a number of significant practical and ethical problems with this statement. It says that librarians affirm rights, but—again—that is beyond their capacity and social license; instead it is the courts that affirm rights, because the asserted rights of one group can sometimes conflict with the claimed rights of others (as we see with the battle over women-only spaces). It charges the library worker with not only “dismantling” systemic biases (not defined), but those in the minds of individual library users as well, a presumptive interference with the sovereignty of individuals to hold particular beliefs and exercise their intellectual freedom – in other words, a violation of the freedom of conscience. Library workers are tasked with confronting inequity and oppression---everywhere? There are no stated limits. They are also to advance social justice in the community beyond the walls of library, and thus their social license.

As John Wright and I argued, applying the discipline of multidimensional library neutrality allows us to retain the spirit of this statement while reigning in its aspirations to within the bounds and license of our practice:

We affirm the inherent dignity and autonomy of all library users (Stakeholder Neutrality), and each user’s right to access the collections and services of the library for their own purposes (Goal Neutrality). We work to recognize and dismantle potential barriers to access [which are created by “wicked” social problems] that may be experienced by members in our communities as a result of their experiences of socioeconomic status, race, sex, ability etc. We work to advance structures and processes that strengthen our profession and our institutions’ abilities to provide all with opportunity for knowledge, education, participation and dialogue (Process Neutrality), through advocacy, instruction, collaboration, services and equitable resource allocation to collections representing multiple points of view, and spaces devoted to free inquiry and encounters with difference (Value Neutrality).

I would anticipate two objections from librarians subscribing to critical social justice—one explicit, the other implicit. The explicitly-stated objection from the literature is that neutrality isn’t just impossible or ahistorical, but is by definition acting passively and standing aside, allowing the perpetuation of injustice. The other more implicit objection is, I think, born of a sense of inadequacy, of—for lack of a better word—jealousy that librarianship isn’t a more intentionally interventionist profession like city planning, and therefore seeks to intervene in and transform society. My response to both objections is the same: that, far from being passive, neutrality in all its dimensions necessitates ongoing and disciplined attention to our engagements with the content of our collections, the nature of our services, the public for whom collections, services, and spaces are intended, and—most importantly—our own intentions regarding all of them. This is the essential intervention that only the publicly-funded library can--alongside the other institutions in the Constitution of Knowledge—offer to democratic societies: to make available for all materials concerning as many diverse perspectives as possible regarding matters of the public interest.

What are the implications of all this for the Association of Library Professionals?

Conclusion

I began this talk by asserting that librarianship is facing not just a crisis of confidence in its own principles and purpose, but is seeing an active, ideological struggle over its future. A significant portion of its literature has for many years now been dedicated to criticizing and condemning the institution and the profession as racist—or guilty of various forms of “--phobias”—and seeks to “disrupt, dismantle and decolonize” it. What is so often missing from these critiques is a cogently-articulated, positive vision of the future for what the library will look like following all this dismantling.

But that is an old Marxist strategy: As Karl Marx himself wrote in a letter to Arnold Ruge in 1843,

...everyone will have to admit to himself that he has no exact idea what the future ought to be. On the other hand, it is precisely the advantage of the new trend that we do not dogmatically anticipate the world, but only want to find the new world through criticism of the old one… I am referring to ruthless criticism of all that exists, ruthless both in the sense of not being afraid of the results it arrives at and in the sense of being just as little afraid of conflict with the powers that be.

I think this is an apt description of #CritLib and its imperative to not just critique the field but to take sides in communities on behalf of some stakeholder groups and against others. But this stance is an untenable one for public institutions dependent on social license and community trust. I think it’s significant that we are seeing North American universities rediscovering this the wake of the Hamas attacks on Israel and the Israeli military response: the realization that (as the 1967 University of Chicago Kalven Report argued) public institutions can only provide a venue, the infrastructure for debating such contentious issues, they cannot themselves adopt a position or they risk alienating significant portions of their constituencies, upon whose financial support and social license they so fundamentally depend.

Other organizations in the public interest are also waking up to the threat represented by the abandonment of institutional neutrality, such as Heterodox Academy and the Foundation Against Intolerance and Racism, or FAIR. Over the past few years I’ve had the pleasure of working with colleagues from Heterodox Academy Libraries, and FAIR in Libraries in the project of defusing the strain of progressive activism that has proven so corrosive to our profession.

But I can’t tell you how much it has meant to me over the past couple of years to have worked with all of you on first the idea—and then the established reality—of the Association of Library Professionals! Four years ago, after running headlong (and painfully) into the clash between the comprehensive doctrine of gender identity ideology and intellectual freedom, I was in a state of professional disillusionment; now I have many new friends and colleagues, and am part of an exciting and galvanizing organization that has real potential to offer a positive vision for the future of non-partisan public library services in pluralist societies, one rooted in traditional ethical principles.

Yet, regardless of one’s political affiliation, I do believe strongly that small c “conservativism” is at the heart of our project, in the sense of the original Latin conservare, which according to the Oxford English Dictionary means to keep or preserve in its existing state from destruction, injury, or change.

I don’t think it’s hyperbolic to argue that what is at stake for librarianship is which—or whose—vision for the profession is going to predominate in the future: one skeptical of (or indeed openly hostile to) the longstanding principles and ethics of the profession and which seeks to supplant them with an imperative to coerce public belief into idealist and divisive comprehensive doctrines, and to intervene in and reshape society—the problems of which it has absolutely no capacity to understand or social license to resolve; or one grounded in an appropriate telos compatible with other liberal democratic institutions, and a positive, ethical, realist conception of the library and its commitments to exercise only “thin” theories of the good in pluralist societies? It is this latter conception that I believe we must conserve.

And while I would confidently position this positive, ethical stance against that of Critical Librarianship, I want to stress that we must not think of ourselves in conflict with those individuals who subscribe to Critical Librarianship. I argue we should recognize that their motivations are admirable, in that they are concerned about pressing social issues such as those related to racism, poverty, and inequality. However, unlike Todd Honma, who speculated in his introduction to Part One of the 2021 book Knowledge Justice: Disrupting Library and Information Studies Through Critical Race Theory, that addressing such issues (and “destroying White Supremacy”) might mean “betraying the profession” of librarianship, I don’t believe we must “betray” or burn our field to the ground and start over. Our task is to convince our colleagues to instead recognize there is a better, more holistic and positive vision for the profession, one that can, I believe, gain wide support from within and without the profession, and which can actually better enable our society to tackle such challenges.

What does this vision look like? I propose that it involves renewing and conserving our profession’s ethical commitments by

Serving the public interest, not a single public good

Acting within the bounds of our social license

Adopting a content-free telos regarding a knowledgeable and literate society

Complementing the role of other liberal institutions, and not usurping their role(s)

Practicing multidimensional library neutrality concerning values, stakeholders, processes and goals;

Emphasizing “thin” procedural theories of the good; and

Taking guidance and inspiration from collaborative urban planning.

This last point is not that same as acting in the domain of planning to bring about radical social transformations, as what I argue critical librarians are presently engaged in, but are doing so without the knowledge, theory, history, discipline and (most essentially) ethical grounding, of the planning profession-–to say nothing of the social license to act in that capacity.

Instead, librarianship inspired and guided by collaborative planning would mean, for example, recognizing community controversies over library materials as a wicked problem originating in multiple causes and viewed by diverse stakeholder groups according to opposing sets of sincerely-held beliefs—one requiring listening, consultation and dialogue, rather than condemnation and accusations. It would mean facilitating debate in library public spaces about matters in the public interest, and not labeling or excluding speakers and audience members with whom one disagrees as bigots. It would mean accounting for the diverse interests of a pluralistic society, rather than assuming—and pursuing—a monoculture of values. It would mean emphasizing processes over outcomes (future seeking, not future-defining). seeking to act in the interests of our users, our communities, and our stakeholders, rather than according to our own ideological purposes, agendas, and ends.

There is, in other words, a rich array of prospects for a profession renewed through the efforts of the Association of Library Professionals, and vitally important work to do. I very much look forward to working with all of you in mapping out the pathways to this renewed practice. Thank you very much.

(Note: This essay has been lightly edited from the original. The author would like to thank Craig Gibson and Sarah Hartman-Caverly for their suggestions and comments on drafts of this essay!)

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer- or editorially-reviewed, all posts and comments must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, submit the Heterodoxy in the Stacks Guest Submission form in the format of a Microsoft Word document, PDF, or a Google Doc. Unless otherwise requested, posts will include the author’s name and the commenting feature will be on. We understand that sharing diverse viewpoints can be risky, both professionally and personally, so anonymous and pseudonymous posts are allowed.

Thank you for joining the conversation!

Margeson, Keahna. "Social license, what is it and why does it matter?" OpenThink, June 2nd, 2022. https://blogs.dal.ca/openthink/part-1-social-license-what-is-it-and-why-does-it-matter/

Congratulations on the ALP and the summit! I too feel that society functions best when entities stick to their original missions as opposed to turning into "activist" organizations all pursuing the same goals.

Thanks again, Michael, for this superlative piece and the keynote address last week at the ALP meeting.