Comment on “Worldliness and Freedom in the Academy”

Readers of Academe deserve better than communist conjecture.

“If we are to see in the idea of perfecting by social action ground for hope about the future, rather than for despair, we need to have some good reason for believing that the perfecting mechanisms will be employed in the interests of freedom rather than in the interests of absolute authority. Without that ground for hope, Marx’s question ‘‘Who shall educate the educators?’’, a question which can be extended to ‘‘Who shall reform the reformers?’’, remains unanswerable. It is one thing to say that the mechanisms for perfecting men are now at our disposal; it is quite another thing to say that they will in fact be used in order to perfect men.”

- John Passmore, The Perfectibility of Man, p. 294

Academe, the magazine of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), is an important and valuable publication covering the higher education landscape. It was with great excitement then, that I saw the Spring 2023 issue was on academic libraries and academic librarians. I quickly read it cover to cover. One contribution stuck out to me as factually and logically flawed, “Worldliness and Freedom in the Academy” by Sam Popowich.1 Intending to correct the record, and riffing on John Passmore’s question of ‘Who shall reform the reformers?’, I have put together this comment.

We get a sense early in the essay of the general approach as well as the sort of tendentious views the editors of Academe are willing to publish. Let us review just a few examples. Popowich notes that the Right is using elected library boards for nefarious purposes. This is true, but there is no mention of similar behavior from the Left such as a book burning in Ontario of items allegedly containing so-called cultural appropriation or which offended indigenous communities.2 He asserts that the idea of Leftist perspectives dominating higher education in North America is an “old canard”. Given the documentation supporting this proposition, Popowich willfully ignores overwhelming evidence or else adheres to an idiosyncratic definition of “the Left”.3 For him, the US Supreme Court’s 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization is not a judgment in favor of political decentralization, or one which returns a policy question into the democratic arena but “an all-out assault on women’s bodily autonomy.” Meanwhile, other literal assaults that are germane to his ultimate conclusion pass without mention.4 However, these are minor quibbles that do not affect the thesis of his essay. The argument briefly restated is:

1) cultural and class struggles are linked,

2) the Right and Left in their political and cultural manifestations are both flavors of liberalism,

3) Right-wing advances in higher education have been achieved through the adoption of a neoliberal economic paradigm,

4) neoliberalism in higher education is causing faculty members and librarians to become proletarianized through the process of subsumption,

5) to consider intellectual and academic freedoms as metaphysically special is a mistake,

6) emphasis on the materialist labor in higher education will place the historic privileges of faculty and librarians on more solid footing through a process involving solidarity with other proletarians and students, and

7) such solidarity requires the rejection of intellectual and academic freedom in the liberal tradition for a communal freedom.

Several of the points (1, 2, 3, and 6) are either unobjectionable or not worth comment here. Point 5 requires brief comment with the key issues being the factual state of point 4 and the errors in reasoning leading to point 7. Regarding point 5, Popowich claims that the standard argument for intellectual freedom in the library discourse “assume[s] that these things [affordable housing, public transportation, etc.] will take care of themselves” and that it relies on “erasing or rejecting the material reality of most people’s day-to-day lives”. This is an uncharitable reading of the literature and overlooks the fact that, whether they are metaphysical or not, intellectual and academic freedom are associated with stable prosperous societies.5 Generations of students who have achieved academically in higher education and have gone on to improve their material condition in life have done so in part due to these freedoms afforded them during their studies. To think that any prosperous society could figure out how to meet the material needs of its citizens without relatively open inquiry and debate strains credulity. With point 5 addressed, we turn now to Popowich’s errors of fact and reasoning.

What Proletarianization?

How are wages in academic libraries determined? Popowich does not pose that question explicitly but the themes he touches on of class struggle and proletarianization typified by “downward pressure on wages, the slashing of benefits, job precarity, and piecework” evince a belief in Marx’s surplus value and subsumption of labor under capital theories. There exists a reasonable body of research on questions of compensation in the profession; most of it can be found with a subject query SU: ((LIBRARY employees' salaries) OR (LIBRARIANS -- Salaries, wages, etc.)) in Library Information Science & Technology Abstracts (LISTA). Two long-running surveys capture real-time descriptive data about salaries in the field. Library Journal’s Placements & Salaries survey has been running for decades and supplies annual snapshots of salaries for recent graduates of LIS programs in the United States. The Association of Research Libraries has published their Annual Salary Survey every year since 2006 reporting high granularity on salaries at member institutions. A detailed analysis would lead us down a path we need not tread as I explain below, but some patterns appear by eyeballing the tables. Geography matters, sex (unfortunately) matters, experience matters, and what appears to matter most is job/position title – presumably, this is dependent on worker skill to some degree. As reported by Library Journal, in 2015 the average salaries of newly minted LIS-holders working as ‘data analyst/scientist’, ‘software engineer/developer’, or ‘UX designer/researcher’ were all over $72,000 USD; meanwhile, recent graduates working as ‘library specialist’ or ‘library technician’ earned ~$34,000 USD.6 Though I could not locate a single LJ Placement & Salaries survey that asked about unionization, evidence from the higher education sector in general shows that it also increases compensation, though the effect is small.7 It is almost as if there is a complex multicausal market for labor setting the wages.8

Two recent studies examine the practice of salary negotiation. A 2018 paper drawing from an ARL sample found that men were more likely to negotiate higher salaries throughout their careers in general while women’s propensity to negotiate increased to the point of exceeding males only when they applied for head/dean/director positions.9 For both sexes self-reported negotiation behavior increased with previous work experience. On average men reported negotiating greater increases than women who also negotiated. Also, a 2021 paper looking at a Canadian sample found men more likely to negotiate but did not collect data on the size of negotiated increases.10 Self-reported negotiation behavior increased, though not by a uniform pattern, with years of work experience. Other older studies support the effect that negotiation plays in setting academic librarian wages. Yet despite my queries in LISTA, I was unable to find a single quasi-experimental study about overall library wage determination, though such studies are available for higher education in general.11 With this cloudy picture, must we adopt Popowich’s understanding of surplus value extraction and Marx’s subsumption of labor theories? No; first because the labor theory of value was decisively refuted over one hundred years ago during the marginalist revolution,12 and second because a cursory look at broadly applicable data shows the opposite of what a proletarianization theory would predict.

To further explore the thesis before turning to the critique of intellectual freedom supposedly implied by the “material realities of education”, we must look at the worldly and easily accessible metric of wages. Long-time readers of Academe know that the magazine is not above publishing tables and charts, so the absence of quantitative evidence supporting Popowich’s argument is notable. What evidence is there for a proletarianization of academic librarians? Let us look at three data points for the United States and Canada: individual income, library expenditure on salary, and salary expenditure per FTE student.

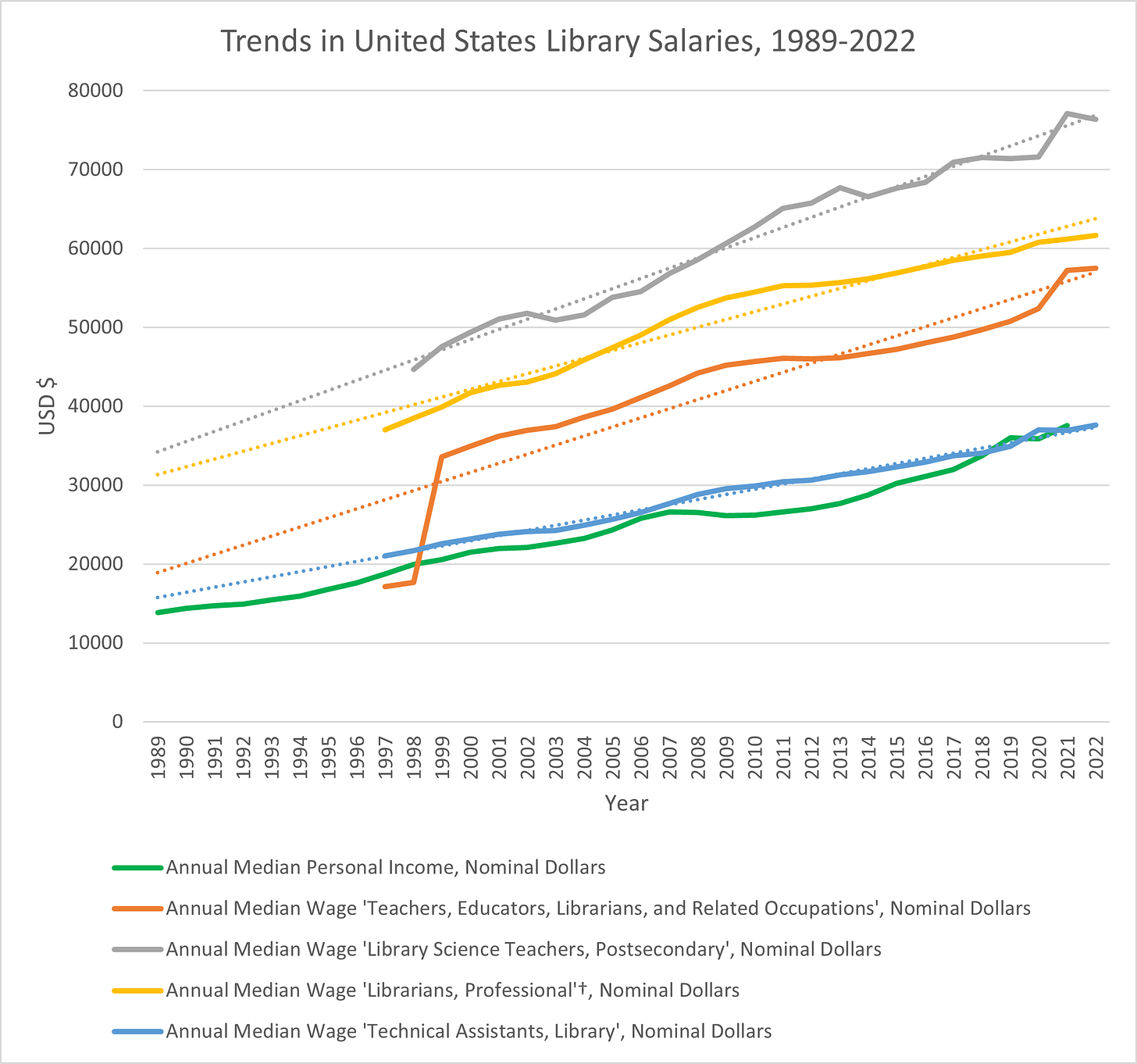

Figure 1: Trends in United States Library Salaries, 1989 - 2022

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Median Personal Income in the United States [MEPAINUSA646N], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MEPAINUSA646N. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor, Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) Survey, retrieved from http://stats.bls.gov/oes/.

† The BLS definition for this occupational classification changed over time; from ‘Librarians, Professional’ to ‘Librarians’ in 1999, and from ‘Librarians’ to ‘Librarians and Media Collection Specialists’ in 2019.

Figure 2: Trends in Canadian Library Salaries, 1989 - 2022

Sources: Statistics Canada. (2022-08-09). Labour income profile of tax filers by sex [Table 11-10-0031-01], retrieved from https://doi.org/10.25318/1110003101-eng.

Kyrillidou, Martha, and Mark Young. 2006. ARL Annual Salary Survey 2005–2006. 2005th–2006th ed. ARL Annual Salary Survey. Association of Research Libraries. https://doi.org/10.29242/salary.2005-2006.

Morris, Shaneka. 2016. ARL Annual Salary Survey 2015-2016. 2015th–2016th ed. ARL Annual Salary Survey. Association of Research Libraries. https://doi.org/10.29242/salary.2015-2016.

All intervening years between the 2006 and 2016 ARL Salary Surveys were consulted as well.

Figure 3: Academic Library Salaries and Wages by Staff Type – United States, 1998 - 2021

Sources: American Library Association, "Academic Library Trends and Statistics Survey", October 8, 2021. http://www.ala.org/acrl/proftools/benchmark/survey.

Figure 4: Academic Library Salaries and Wages by Staff Type – Canada, 1998 - 2021

Sources: American Library Association, "Academic Library Trends and Statistics Survey", October 8, 2021. http://www.ala.org/acrl/proftools/benchmark/survey.

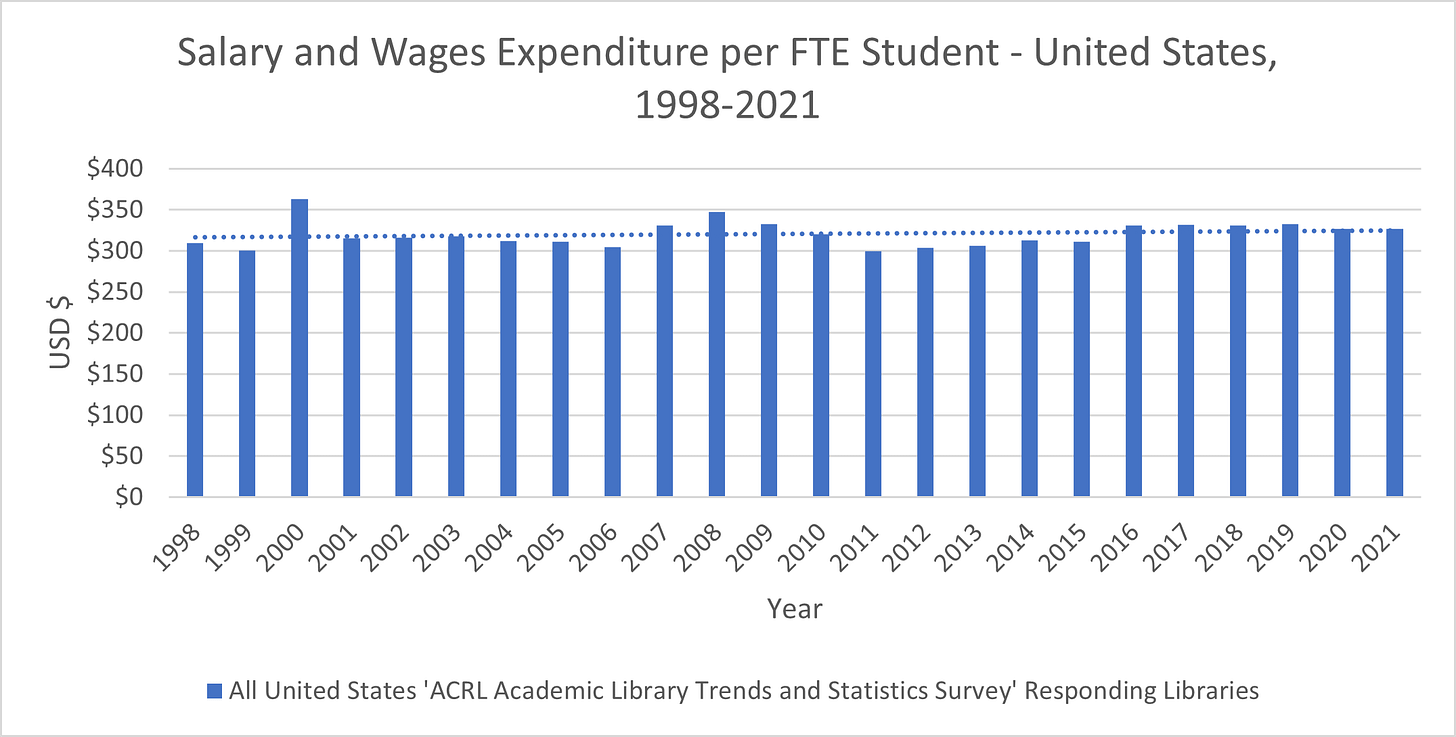

Figure 5: Academic Library Salary and Wages Expenditure per FTE Student – United States, 1998 - 2021

Sources: American Library Association, "Academic Library Trends and Statistics Survey", October 8, 2021. http://www.ala.org/acrl/proftools/benchmark/survey.

Figure 6: Academic Library Salary and Wages Expenditure per FTE Student – Canada, 1998 - 2021

Sources: American Library Association, "Academic Library Trends and Statistics Survey", October 8, 2021. http://www.ala.org/acrl/proftools/benchmark/survey.

Figures 1 and 2 review easily available data on median personal income and library salary data for the United States and Canada during Popowich’s period of supposed proletarianization. In Figure 1, we see that median personal income has increased over the period and that librarian salaries according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) categories for ‘Librarians, Professional’, ‘Library Science Teachers, Postsecondary’, and ‘Teachers, Educators, Librarians and Related Occupations’ are continually increasing and almost always above the median income. The BLS category for ‘Library Assistants, Technical’ tracks median income closely. The Canadian data was less familiar to me, however using data from Statistics Canada (StatCan) and freely available Association of Research Libraries salary surveys I have shown that Canadian median personal income increased over the period and that librarian salaries at ARL libraries in Canada were consistently paid above the median and increased at a rate higher than the median. These data are the opposite of what anyone would expect to see if proletarianization were a monetary phenomenon.

How about the money that libraries expend on their workforce? Figures 3 and 4 display data from the Association of College & Research Libraries' annual Academic Library Trends and Statistics survey. This data covers 1998 through 2021. Definitional changes in reporting complicate the picture slightly but the clear fact that there has been no decline is obvious; again, this is contrary to a proletarianization narrative. What about the amount of ‘work’ paid for per full-time equivalent student? This is a crude measure of efficiency, if proletarianization were happening, we might expect to see library deans or directors ‘extracting’ more value out of their labor force by working them harder as the student population increases, the wages per FTE would trend downward in other words. However, in the real world, the one where the labor theory of value has been decisively discredited, we see a stable efficiency trend in Figure 5 for the United States and a decreasing efficiency in Figure 6 for Canada.

We can also look at the question of job satisfaction to inform the proletarianization thesis. To do this I queried Library Information Science & Technology Abstracts (LISTA) for: ((“job satisfaction” OR “work satisfaction” OR “employee satisfaction”) AND (university OR college OR academic) AND survey). Data on this is sporadic but small and medium sample-size studies from the United States and Canada provide some context. A 1978 study found an average satisfaction score of 2.79 on a 5-point scale for working conditions and general satisfaction scores of 3.08 for reference librarians and 3.01 for catalogers.13 A 1985 study of Brigham Young University librarians found an overall job satisfaction score of 3.87 on a 5-point scale.14 These two studies being before 1989, which is where Popowich’s narrative of proletarianization starts, serve as a benchmark. How stand sentiments of satisfaction over time? A 1990 study of workers in the University of California libraries measured overall job satisfaction on a 5-point scale and recorded that of librarians 31% were “very satisfied” and 44% were “satisfied”. That same study found sentiments for library assistants at 20% “very satisfied” and 30% “satisfied”.15 Bonnie Horenstein published a job satisfaction study of United States academic librarians in 1993 which was later replicated in a Canadian sample. She found that on a 5-point scale, the average overall job satisfaction score was 3.52.16 The Canadian study was published in 1997 and found an overall job satisfaction score of 3.59.17 A 2004 study of library workers in Louisiana found that 84% of respondents were satisfied with their occupation.18 A 2007 study of academic library information technology workers found an average overall job satisfaction score of 3.72 on a 5-point scale.19 Library Journal’s 2008 Job Satisfaction Survey found that 70% of respondents were either “very satisfied” or “satisfied” with their job; approximately half the respondents were from academic libraries.20 A 2012 study, with a sample not including whites, found that a “majority of respondents (61.6%) were satisfied with their libraries as a place to work”.21 A 2015 survey of access services employees found 22% of respondents “very satisfied” and 54% of them “satisfied” overall.22 A 2019 study found an overall average career satisfaction score of 4.07 on a 5-point scale. That same study noted that the lowest scores were observed in nontenure-eligible librarians working in environments with tenure and that the hiring of such workers had increased between 2010 and 2015.23 A 2020 study recorded an average job satisfaction score of 139.4 out of 216, technically ‘ambivalent’ according to the study measure but no statistically significant differences were found based on job component, gender, race, or library type (i.e. public or academic).24 Furthermore, a 2020 study on work-life balance found that “the majority of the respondents reported satisfaction (57%)”.25 If Popowich’s narrative were true, we might expect to see some combination of declines in satisfaction or complaints about compensation as the main reason librarians leave the field. Contrary to that, a 2020 study found that “employees are not fleeing their positions, they are fleeing work environments they feel are toxic.” That same study also found that dissatisfaction with current or future salary was the second most important factor behind turnover. Yet this cannot be attributed to purely materialist forces as Popowich might want, qualitative analysis showed that inequity (low performers rewarded, favoritism, flashy digital librarians being paid more than instruction librarians, etc.) was important. Social forces such as envy – which the analysis in the Academe essay ignores – remain powerful. While job satisfaction data does not conclusively disprove the proletarianization hypothesis, it clearly does not support it.

Figure 7: Academic Library Job Satisfaction Scores on a Likert 5-Point Scale

Sources: Various studies mentioned in-text and cited in the endnotes.

† All samples included academic library workers but not all were exclusive to that population.

None of this is to say that academic librarians, much less public librarians, or library workers in general, are adequately compensated for their physical, emotional, and intellectual labor. The literature is peppered with studies detailing many problems of mismanagement, underfunding, unrequested political influence, increasing reliance on adjuncts, burnout, and intra-library-worker conflict. The historically feminized pink-collar nature of the industry has surely artificially depressed wages to some degree. Many libraries, archives, and museums have supplemented their workforce through grant-funded labor. Those grant positions in particular place contingent workers in extremely uncomfortable and precarious positions (metaphorically and literally). Excellent work on this subject under the auspices of the Digital Library Federation (DLF) with funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services has explained the genesis of precarious grant-funded labor and outlined achievable solutions.26

My critique here is that rising individual salaries, rising library expenditure overall on salaries, flat or rising salary expenditure per FTE student, and flat job satisfaction scores all contradict a proletarianization thesis. On balance the data do not support a “capitalist exploitation” narrative, the burden of proof is clearly upon Popowich to offer quantifiable information to support his thesis. His sole piece of evidence is anecdotal: in what will surely come to be regarded as a mistake, Texas A&M University rescinded tenure protections for librarians and cut staffing in 2022.27 Also, public librarians are being subjected to excessive scrutiny and retaliatory funding decisions in some Republican-governed geographies.28 But Popowich’s thesis is about academic librarians, one data point at TAMU does not a trend make. Bolstering his case by including the grant-funded precariat is not sufficient to prove the point. The aforementioned DLF study on precarity garnered 100 participants, compared with the approximately 9,000 members of ACRL and the even larger population of all academic library workers; <1% of a workforce does not a trend make.29 With job satisfaction stable, the argument for proletarianization is anecdotal at best without empirical data about non-monetary “material struggles”. This is not to declare finally that proletarianization is impossible, but Popowich’s reliance on unrepresentative data points is a fallacious hasty generalization.

Fobazi Ettarh’s work on vocational awe, referenced by Popowich, is clearly relevant here. To rephrase her under-compensation thesis in the terms of this discussion, library workers who adopt vocational awe (the actual awe, not the critique) receive psychic income – “subjective pleasures flowing to an individual person in a specified period”30 - knowing they have “done good work”.31 Library administrators should, of course, provide adequate monetary compensation to their workers and not prey on their good nature. But an uncomfortable conclusion arises, not discussed by either Ettarh or Popowich, that workers themselves have some agency in their total (monetary and psychic) incomes derived from library work. Those maintaining hope about the future who can muster vocational awe may accrue extra (psychic) income; those who despair and critique vocational awe may feel more proletarianized. A curious tension also exists by way of Popowich’s use of the vocational awe concept because Ettarh has explicitly argued against mission creep towards the provision of services aimed at alleviating users’ material struggles: “If we’re trying to be librarians and also social workers and also mental health professionals and also community centers, there’s no way that any one space can do all of that well, and so we’re doing all of that badly. I think it would make more sense for us to do the job we’re trained for: information specialists.”32

Relative immiseration remains a possibility, such as through multicausal declines in purchasing power or loss of social status, though this does not appear to be what Popowich is arguing. Mismanaged monetary and fiscal policy associated with inflation surely contribute to any relative immiseration but the US Federal Reserve and Bank of Canada are not mentioned in the essay, the target instead being amorphous “capital” defined as “corporate interests linked with university administrations”. Though the proletarianization thesis is lacking empirical support, Popowich is spot on in his identification of a process whereby an intersectional class of workers, employed by capital, “leverages diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to bring about … less diverse” economies and societies. The concept capturing this process is ‘woke’ capital.

Helen Lewis, writing in The Atlantic in 2020 articulated what she called “the ‘iron law of woke capitalism’: Brands will gravitate toward low-cost, high-noise signals as a substitute for genuine reform, to ensure their survival.”33 That principle parsimoniously explains many high- (and low-) profile firings in the public and private sectors that she reviewed. Why should managers give raises to underpaid employees when they can just as easily send everyone to diversity training or a seminar about white supremacy? Such training and seminars offer minimal disruption to existing power structures. The underlying logic is clear and broadly similar to the point that Popowich quotes Stuart Hall as making: social radicalism is far less costly and disruptive than economic radicalism. How does this result in a less diverse, less fair economy? ‘Woke’ rhetoric by capital can be viewed as a placebo that takes the place of higher wages, improved working conditions, or better benefits. In a society where civic institutions have weakened, brand loyalty can offer a degenerated substitute; socially liberal or Left views on non-economic issues have become more popular with younger consumers and are gaining ground among the affluent. ‘Woke’ marketing is simply a good customer acquisition and retention practice.34 Such brand positioning is not only justified on market research grounds, but it may also pay real political dividends as well. By supporting identity politics, DEI initiatives, and other causes such as global warming mitigation, ‘woke’ businesses hope to be spared increased taxes, increased regulation, and/or antitrust scrutiny. With the Republican and Conservative Party of Canada already pro-business/pro-corporate, the ‘woke’ strategy offers almost no downside politically as it seeks to please the Democratic and Liberal parties. Clear ‘material’ effects come through the adoption of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals and policies. Normally disciplined through profit and loss accounting, the ‘woke’ capital strategy allows for a loosening of certain constraints on management (‘We would have made the 8 percent target, but we had additional nontraditional stakeholder expenditures.’)35 When such ESG requirements are mandated, they reduce the diversity (in an ecological sense) of production possibilities. To the extent adopting ESG is profitable, it has been and could be adopted voluntarily.36 If the concept of ‘profit’ is expanded to include nonpecuniary spheres, the logic and critique above might also apply to higher education. Though Popowich brushes off “wokeness” as something “the Right has decried” early in his essay, by his own logic of class struggle and solidarity it should be a target of critique; instead, he chooses to construct castles in the air.

Metaphysics and Non-Sequiturs

After speculating about class struggle, Popowich turns to the material realities of education and how academic and intellectual freedom must not rise above them. This is a deep point and his example from Brecht ably shows that a subsistence floor must be achieved. But this ‘by-degree’ argument may not support Popowich’s thesis as first appears. Readily available contemporary counterexamples include starving artists and penniless musicians who exercise their mental freedoms to participate in public intellectual life. An amusing historical counterexample is Diogenes of Sinope; he was unhoused, living in a tub, and yet practiced his philosophy with such freedom and spirit that he is remembered more than 2300 years later today.37 Also, Popowich writes that “only those who can get to a library or afford private internet services can partake in library supported intellectual freedom.” Granting that premise, it is a non sequitur to conclude, as he later does, that intellectual freedom must be re-evaluated. Rather, this is a compelling argument for the expansion of library services such as bookmobiles, small branch libraries, library-funded Wi-Fi hotspots, or municipal/community broadband or mesh networks. While an absolutist stance that material concerns must necessarily precede participation in intellectual life seems true, the barriers to entry are incredibly low. In our present age, this is thanks in no small part to the work of public libraries which offer no-fee access to computers connected to the internet. What is strange is that Popowich clearly understands the logic of ‘by degree’ argumentation and uses it when discussing the “enormous privileges” of academic librarians. Why then, is a ‘by degree’ argument for liberal intellectual freedom not entertained? Popowich states that the process of proletarianization is one of degree but intellectual freedom is a “metaphysical notion” which simply must be displaced.

This brings us to the close of Worldliness and Freedom in the Academy where readers are informed: “we must reject the individual, idiosyncratic notion of freedom proper to liberalism … and instead embrace a communal, shared freedom that owes its very existence to cooperation and collective life.”38 What would this mean in practice? He humbly notes that it would be difficult to predict but quickly gives readers a glimpse of this potential future. By his own admission, “shared freedom” involves “excluding transphobic or racist speakers”.39 Freedom then hinges on who gets to define ‘transphobic’ or ‘racist’ to exclude whom. That question is beyond the scope of the original essay as well as this comment but the parallels with the Leninist logic and slogan “Who Whom?” are notable.40 To paraphrase the epigraph from Passmore at the opening, it is one thing to say that the mechanisms for achieving shared freedom are possible; it is quite another to say that they will in fact be used for sharing freedom.

In his discussion of cultural and class struggles, Popowich points readers to the work of Stuart Hall. Hall offered a critique that in our society, one ‘structured in dominance’, capital working through racism divides classes against themselves thereby neutralizing anti-capitalist social alternatives. Might communal shared freedom allow escape from the dominance structure? Though difficult to predict, we can get a glimpse of what Popowich’s “shared freedom” means by looking at the 2021 Open Letter to the CFLA Board On Intellectual Freedom, which he signed, that states: “To be clear, we believe that intellectual freedom is a complex issue worthy of discussion; the humanity and fundamental right to gender expression for trans people is not. CFLA needs to reckon with what happens when abstract principles are prioritized over real people’s lives.”41 The human right to gender expression, itself a “metaphysical symbol”42 but backed by the Canadian state,43 trumps the freedom to interrogate the phenomenon of transsexuality in a library. Though Popowich critiques intellectual freedom as having a privileged metaphysical place, his argument from transmisia reduces to a metaphysical one as well. If escape from a society ‘structured in dominance’ is possible, a communal or shared freedom in which only those with the approved thought and speech may use a library is certainly a society in which dominance relations are retained. To paraphrase Passmore’s question in the epigraph, ‘Who shall define human rights for the reformers?’ Popowich’s “shared freedom” in which “there is no such thing as not taking a side” aims to reject and displace a time-tested freedom afforded to all. He falls directly into what sociologist Ilana Redstone calls ‘the certainty trap’. As explained earlier in Heterodoxy in the Stacks, that trap is particularly fraught for taxpayer-funded institutions and plainly incompatible with humility, fallibilism, and the ethical diversity present in society.44

Even though it required this comment, Academe’s decision to publish the essay proves that the candle of intellectual freedom proper to liberalism is still burning. The embrace of a communal, shared freedom is not (yet) a mainstream idea. Entire publications such as The Journal of Intellectual Freedom & Privacy operate under a liberal(ish) understanding of intellectual freedom; national and international library organizations have statements attesting to its importance.45 In 2020 Dani Scott and Laura Saunders showed that the concept of ‘neutrality’ also has a professional consensus, though not without some disagreement on edge cases and extreme scenarios.46 Rejecting the notion of freedom proper to liberalism would likely require changes in policy and the hearts and minds of many librarians the world over at minimum; maximal rejection would require an authoritarian state, which may be what Popowich ultimately has in mind.47 The proposal is, in short, an exercise in intellectual freedom. Popowich put forth a novel idea outside the mainstream; and, he did it from Winnipeg. He concludes then by refuting himself, showing that “intellectual freedom on stolen land” is possible after all.48

In closing, it is worth highlighting that library workers have a professional calling, with a core set of values and ethics that have endured and which are continuing to adapt to social realities.49 Libraries as institutions and librarians find common ground with all their constituents, including the ‘proletariat’ in Popowich’s terms, most effectively through our professional calling and our adherence to liberal values. Intellectual freedom and the absence of governmental viewpoint discrimination are crucial conditions for community formation. We should aspire to libraries that facilitate people beginning to understand those with different perspectives, learning to respect others, and compromising with them on the playing field of citizenship. Readers of Academe deserve better than communist conjecture.

Acknowledgments

Craig Gibson provided helpful comments on the first draft of this manuscript. Any errors are my own.

Popowich, Sam. 2023. “Worldliness and Freedom in the Academy.” Academe 109 (2):25-29. https://www.aaup.org/article/worldliness-and-freedom-academy.

Dawson, Tyler. 2021. “Book Burning at Ontario Francophone Schools as ‘gesture of Reconciliation’ Denounced.” National Post (Online), September 7, 2021, sec. Canada. https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/book-burning-at-ontario-francophone-schools-as-gesture-of-reconciliation-denounced.

See:

Eagan, M. K.; Stolzenberg, E. B.; Berdan Lozano, J.; Aragon, M. C.; Suchard, M. R.; Hurtado, S. (November 2014). Undergraduate Teaching Faculty: The 2013–2014 HERI Faculty Survey. Higher Education Research Institute. https://www.heri.ucla.edu/monographs/HERI-FAC2014-monograph.pdf.

Langbert, Mitchell. 2018. “Homogenous: The Political Affiliations of Elite Liberal Arts College Faculty.” Academic Questions 31 (2): 186–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12129-018-9700-x.

Kaufmann, Eric. "Academic Freedom in Crisis: Punishment, Political Discrimination, and Self-Censorship." Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology, March 1st, 2021. https://cspicenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ESummary.pdf.

On the Canadian context, in reply to a question asking professors to place themselves on a left-right spectrum where 1=left and 7=right, 55.6% of respondents placed themselves as left-leaning with scores of 1, 2, or 3. Only 14% placed themselves as right-leaning with scores of 5, 6, or 7. Nakhaie, Reza, and Barry Adam. 2008. “Political Affiliation of Canadian Professors.” Canadian Journal of Sociology 33 (4): 873–98. https://doi.org/10.29173/cjs1036.

See:

Hammer, Alex. 2022. “Man Arrested after Punching Cop at Drag Event at NY Public Library.” Daily Mail Online, December 11, 2022, sec. News. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11526151/Man-arrested-punching-cop-drag-story-event-New-York-Public-Library-Manhattan.html.

Talarico, Lauren. 2019. “Houston Public Library Admits Registered Child Sex Offender Read to Kids in Drag Queen Storytime.” KHOU-TV, March 6, 2019, sec. Local. https://www.khou.com/article/news/local/houston-public-library-admits-registered-child-sex-offender-read-to-kids-in-drag-queen-storytime/285-becf3a0d-56c5-4f3c-96df-add07bbd002a.

The extent of a causal relationship is the subject of ongoing research and debate. See: "press freedom index" "economic freedom" - Google Scholar and "democracy index" "economic freedom" - Google Scholar

Allard, Suzie. 2015. “The Expanding Info Sphere. (Cover Story).” Library Journal 140 (17): 24–30.

Hedrick, David W., Steven E. Henson, John M. Krieg, and Charles S. Wassell Jr. 2011. “Is There Really a Faculty Union Salary Premium?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 64 (3): 558–75.

A point which Popowich does not make in his essay, but which supports his thesis, is that accredited LIS programs produce far too many graduates for the number of available positions in the sector. In the Marxist sense, these misemployed (or unemployed) holders of the credential constitute a massive “reserve army of labor”. Such a large misalignment surely contributes to lower wages than what librarians would be able to earn ceteris paribus with a smaller number of credentialed competitors. There is substantial literature on the oversupply of PhDs, and the subject of librarian oversupply is under-researched. Querying LISTA for the word ‘oversupply’ and restricting the search to peer-reviewed journals, I find only one result. Interestingly, that article claimed that “librarians have the most precarious professional lives in all of academe” and complained about market saturation depressing wages. It was published in 1981, eight years before Popowich’s neoliberalism benchmark. See:

MacLeod, Murdo J. 1981. “Some Social and Political Factors in Collection Development in Academic Libraries.” Journal of Academic Librarianship 7 (3): 146.

Silva, Elise, and Quinn Galbraith. 2018. “Salary Negotiation Patterns between Women and Men in Academic Libraries.” College & Research Libraries 79 (3): 324–35. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.3.324.

Cardozo, Paula, and Emma Scott. 2021. “Employment Negotiation Behaviours of Canadian Academic Librarians: An Exploratory Study.” Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research 16 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v16i1.6129.

Using longitudinal data from the various Library Journal and ARL Salary Surveys, one might be able to provide a rigorous answer to questions of library wages. I hope some enterprising scholar takes this project on as it is a serious gap in the LIS literature.

See:

“Criticisms of the Labour Theory of Value.” 2023. In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Criticisms_of_the_labour_theory_of_value.

Prychitko, David. 2007. “Marxism.” In Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, edited by David R. Henderson. Carmel, IN: Liberty Fund. https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/Marxism.html.

Chwe, Steven Seokho. 1978. “A Comparative Study of Job Satisfaction: Catalogers and Reference Librarians in University Libraries.” Journal of Academic Librarianship 4 (3): 139.

Bengston, Dale Susan, and Dorothy Shields. 1985. “A Test of Marchant’s Predictive Formulas Involving Job Satisfaction.” Journal of Academic Librarianship 11 (2): 88.

Kreitz, Patricia A., and Annegret Ogden. 1990. “Job Responsibilities and Job Satisfaction at the University of California Libraries.” College & Research Libraries 51 (4): 297–312. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_51_04_297.

Horenstein, Bonnie. 1993. “Job Satisfaction of Academic Librarians: An Examination of the Relationships Between Satisfaction, Faculty Status, and Participation.” College & Research Libraries 54 (3): 255–69. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_54_03_255.

Leckie, Gloria J., and Jim Brett. 1997. “Job Satisfaction of Canadian University Librarians: A National Survey.” College & Research Libraries 58 (1): 31–47. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.58.1.31.

Goetting, Denise. "Attitudes and job satisfaction in Louisiana library workplaces." Louisiana Libraries 67, no. 1 (2004): 12-17.

Lim, Sook. 2007. “Library Informational Technology Workers: Their Sense of Belonging, Role, Job Autonomy and Job Satisfaction.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 33 (4): 492–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2007.03.007.

Albanese, Andrew Richard. 2008. “Take This Job and Love It.” Library Journal 133 (2): 36–39.

Damasco, Ione T., and Dracine Hodges. 2012. “Tenure and Promotion Experiences of Academic Librarians of Color.” College & Research Libraries 73 (3): 279–301. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-244.

Sewell, Bethany Badgett, and Charla Gilbert. 2015. “What Makes Access Services Staff Happy? A Job Satisfaction Survey.” Journal of Access Services 12 (3–4): 47–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/15367967.2015.1061435.

Becher, Melissa. 2019. “Understanding the Experience of Full-Time Nontenure-Track Library Faculty: Numbers, Treatment, and Job Satisfaction.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (3): 213–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.02.015.

Martin, Jason. 2020. “Job Satisfaction of Professional Librarians and Library Staff.” Journal of Library Administration 60 (4): 365–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2020.1721941.

Townsend, Tamara, and Kimberley Bugg. 2020. “Perceptions of Work–Life Balance for Urban Academic Librarians: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Library Administration 60 (5): 493–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2020.1729624.

Rodriguez, Sandy, Ruth Tillman, Amy Wickner, Stacie Williams, and Emily Drabinski. 2019. “Collective Responsibility: Seeking Equity for Contingent Labor in Libraries, Archives, and Museums.” Digital Library Federation. https://osf.io/m6gn2.

Peet, Lisa. August 2022. “Texas A&M Rescinds Librarian Tenure.” Library Journal 147 (8):11-13.

Harris, Elizabeth A., and Alexandra Alter. 2022. “With Rising Book Bans, Librarians Have Come Under Attack.” New York Times (Online), July 6, 2022, sec. Books. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/06/books/book-ban-librarians.html.

American Library Association. August 2, 2011. "About ACRL", http://www.ala.org/acrl/aboutacrl (Accessed May 6, 2023)

Rutherford, Donald. 2012. “Psychic Income.” In Routledge Dictionary of Economics, 484. Taylor & Francis Group. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Ettarh, Fobazi. 2018. “Vocational Awe and Librarianship: The Lies We Tell Ourselves.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe, January, n.p. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2018/vocational-awe/.

Ford, Anne, Chera Kowalski, Tom Rink, Graham Tedesco-Blair, Homa Naficy, Amanda Oliver, Nicole A. Cooke, and Fobazi Ettarh. 2019. “Other Duties as Assigned.” American Libraries 50 (1/2): 40–47.

Lewis, Helen. 2020. “How Capitalism Drives Cancel Culture.” The Atlantic, July 14, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/07/cancel-culture-and-problem-woke-capitalism/614086/.

Barro, Josh. 2018. “There’s a Simple Reason Companies Are Becoming More Publicly Left-Wing on Social Issues.” Business Insider, March 1, 2018. https://www.businessinsider.com/why-companies-ditching-nra-delta-selling-guns-2018-2.

Cwik, Paul. 2022. “Wilson, Waldo, Woke CEOs, and Ways Forward.” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 25 (2). https://doi.org/10.35297/qjae.010131.

Sanjai Bhagat and Todd J. Zywicki, opinion contributors. 2021. “Does the Market Care about Ethical Investment? It Depends.” The Hill. September 13, 2021. https://thehill.com/opinion/finance/571962-does-the-market-care-about-ethical-investment-it-depends/.

Piering, Julie. n.d. “Diogenes of Sinope (c. 404—323 B.C.E.).” In The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ISSN 2161-0002. Accessed May 6, 2023. https://iep.utm.edu/diogenes-of-sinope/.

Popowich, 29.

Astute readers will note the fact that in the second paragraph of Worldliness and Freedom in the Academy “cancel culture” is wrapped in scare quotes and named as a grievance of the Right. Would it at least lose scare quotes if a Popowich-ian library canceled a “racist”?

Lest I be accused of introducing Lenin as an ad hominem, let the record show that Sam is a soi-disant Marxist and writes things such as: “‘Ruthless Criticism of All That Exists’: Marxism, Technology, and Library Work.” That chapter appeared in The Politics of Theory and the Practice of Critical Librarianship, edited by Karen Nicholson and Maura Seale published by Library Juice Press. I quite enjoyed it.

MacCallum, Lindsey, Brianne Selman, Elizabeth Stregger, et al. 2021. “Open Letter to the CFLA Board On Intellectual Freedom,” September 2021. https://cfla-fcab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Open-Letter-to-the-CFLA-Board-On-Intellectual-Freedom.pdf.

Lucid critiques of human ‘rights’ include:

Heard, Andrew. 1997. “Human Rights: Chimeras in Sheep’s Clothing.” https://www.sfu.ca/~aheard/intro.html.

Husak, Douglas N. 1984. “Why There Are No Human Rights.” Social Theory and Practice 10 (2): 125–41. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23556556.

Scruton, Roger. 2010. “Nonsense on Stilts.” Handbook of Human Rights, 118-128.

See for examples:

Blackwell, Tom. 2022. “Grade 1 Teacher Who Said Boys and Girls No Different in ‘Gender Fluidity’ Lesson Cleared by Rights Tribunal.” National Post (Online), September 6, 2022, sec. Canada. https://nationalpost.com/news/canada/grade-1-teacher-who-said-boys-and-girls-no-different-in-gender-fluidity-lesson-cleared-by-rights-tribunal.

Brown, Jon. 2023. “Teen Suspended for Opposing Trans Ideology Files Human Rights Complaint: ‘Shockingly Discriminatory.’” Fox News Digital, April 16, 2023, sec. World. https://www.foxnews.com/world/teen-suspended-opposing-trans-ideology-files-human-rights-complaint-shockingly-discriminatory.

Shah, Furvah. 2021. “Trans, Non-Binary Server Awarded $30,000 in Employment Dispute over Pronouns.” The Independent, October 4, 2021, sec. Americas. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/canadian-tribunal-transgender-nonbinary-restaurant-worker-pronouns-b1931972.html.

Dudley, Michael. 2022. “The Certainty Trap and ‘Taking Sides’ in Librarianship.” Heterodoxy in the Stacks (blog). June 3, 2022. https://hxlibraries.substack.com/p/the-certainty-trap-and-taking-sides.

The October 2022 issue of IFLA Journal (Vol. 48 Issue 3) was devoted to discussion of the 1999 IFLA Statement on Libraries and Intellectual Freedom <https://repository.ifla.org/handle/123456789/1424> and provides a nice summary of the present state of thought.

Scott, Dani, and Laura Saunders. 2021. “Neutrality in Public Libraries: How Are We Defining One of Our Core Values?” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 53 (1): 153–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000620935501.

Popowich, Sam. 2019. Confronting the Democratic Discourse of Librarianship: A Marxist Approach. Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press.

Notably, he writes on the subject of internet regulation: “The choice is not between the liberal illusions of pure, individual freedom against tyranny, the choice is between both corporate and state tyranny on the one hand and a collective commitment to concrete social justice on the other.” That collective commitment would require “interven[ing] explicitly in the intellectual and cultural lives of our fellow citizens (defined as broadly as possible)” (p. 294). Regarding the environmentalist imperative of saving the planet, he concedes this may necessitate “the Leninist and Maoist insistence on the party-form, dictatorship, and people’s war;” or other coercive means to “force” those he perceives in opposition to that goal to “stop [and] fall in line, [which] will require a serious rethinking of democracy and political theory” (p. 298).

While the larger point about stolen land is applicable to the United States and Canadian context, Winnipeg specifically is located on land ceded by the indigenous communities of Long Plain, Sagkeeng, Brokenhead Ojibway, Sandy Bay Ojibway, Swan Lake, Peguis, and Roseau River Anishinaabe under Treaty 1 in 1871. Wikipedia informs us that almost immediately the treaty was considered controversial and remains so. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_1

American Library Association. July 28, 2021. "ALA adopts new Code of Ethics principle on racial and social justice", http://www.ala.org/news/member-news/2021/07/ala-adopts-new-code-ethics-principle-racial-and-social-justice.

This well-researched rejoinder is so valuable: many thanks for putting in the work! Watching academics (and apparently librarians) larp about their solidarity with the working class is one part trainwreck (horrible horrible) to one part slapstick (ludicrous ludicrous). That all of their most cherished shibboleths and jargon ("transmisia" good googeldy mooks) are fully and ferociously backed by late modern capitalist imperialism (Target's "progress flag" product lines; Army recruitment ad featuring a drag queen) gives them no pause atall.

The shape of the pegs and holes never really matters; Marxism is a sledgehammer and when a wielder like Popowich wants something to fit in the round hole....WHAM! WHAM! WHAM!...there. You're proletarianized. And, of course, an attack on intellectual freedom is par for the course.