Bohemian rhapsody

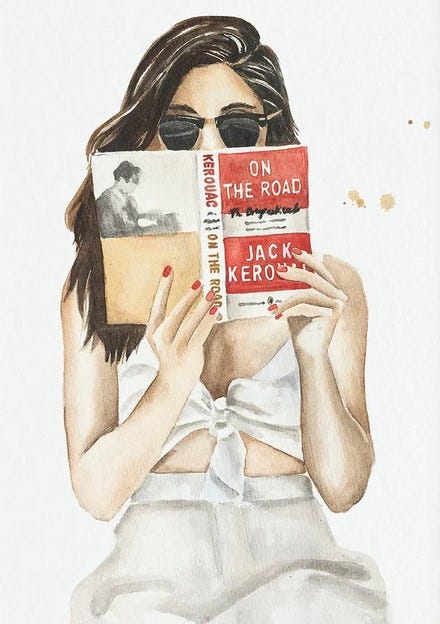

There is a coffee shop. The coffee shop is also a bookstore, and the walls are adorned with photographs, drawings, and paintings that celebrate reading: people reading in bathtubs and in fields, formal portraits of society ladies holding books, people reading while in various stages of undress. One drawing portrays a chic young woman in sunglasses reading Beat classic On the Road. It is a striking image: light and bright, cheerful even. This drawing, in concert with all the other pieces on the walls, seems to proclaim: everyone reads! Or maybe, to paraphrase the late George Michael: reading is natural, reading is good, not everybody does it, but everybody should.

About a month ago I stood in line at this coffee shop/bookstore, and heard the following exchange between a man and woman behind me:

Man: Do you see a lot of young ladies reading Kerouac?

Woman: Mmm.

Man: He’s not really known for writing from a woman’s perspective.

There I stood, feeling strangely confrontational for someone in an establishment that sells handsome hardcovers and golden turmeric lattes. A series of questions formed in my mind: are we only supposed to read that which reflects one’s perspective? What is a “woman’s perspective”? Can readers not identify with experiences that are not specifically their own? Some would say the point of reading, especially fiction, is to explore different perspectives!

In any case, this interrogation occurred only in my ridiculous imagination. I retrieved my order (drip coffee and plain croissant, both quite good) and returned to my seat. As I reflected on the Kerouac moment, my mind wandered to recent highly publicized controversies around banned books. To my knowledge, On the Road is not a frequently challenged book. But the notion of the conventionally attractive young woman as an unlikely reader of the adventures of Dean Moriarty and Sal Paradise got me thinking of other strange juxtapositions, as well as some of the limitations of mainstream discourse around intellectual freedom.

Rules for thee, not for me

I am going to assume that anyone reading this Substack is well-versed in the history of banned books and intellectual freedom. You know that librarians and intellectual freedom advocates often use “banned” as shorthand for any item that is challenged in a collection. You know that censorship encompasses more than items being expunged from a collection: library censorship occurs when a selector declines to bring an item into the collection in the first place. A less overt but nevertheless type of censorial behavior is when a controversial item is relocated to a restricted area. You know that the American Library Association has guidelines on labeling systems, and endorses viewpoint neutral guidance while warning against prejudicial labels. Finally, you are likely well aware that the vast majority of high-profile attempts to ban books have come from very conservative quarters, and this continues to be the trend. Sexual content, crude language, and/or defying religious dogma have been core features of book challenges, particularly when items are seen as having the potential to corrupt youth. The most banned book of 2021 was Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe.

And yet…while the American Library Association officially promotes viewpoint diversity, I cannot help thinking that banned books messaging has become increasingly predictable and one-sided. It does not seem to be as much about building a broad coalition around the protection and promotion of free speech as it is the perpetuation of a feedback loop. The most prominent intellectual freedom advocates seem at the ready to condemn any challenge from conservative-leaning parties, yet curiously detached when the challenge comes from the left-progressive end of the spectrum. It is the same people promoting the same talking points about the same titles.

Let us just go all in on a third rail topic: how should libraries handle calls to censor so-called “gender critical” views, given that many claim any tolerance of these views directly threatens the safety of transgender people? In 2020 the Seattle Public Library permitted a controversial organization, the Women’s Liberation Front (WoLF) to reserve a room in accordance with the library’s meeting room policy. Depending on your perspective, WoLF is either a feminist organization promoting sex-based rights; or a hate group that denies the existence and humanity of transgender people. SPL was inundated with calls to cancel the event. Eventually then-director Marcellus Turner announced his decision: the event would be held, though after regular library operating hours, and with the explicit understanding that SPL did not endorse the views of WoLF or its supporters. While many wished for SPL to cancel the event, there were many others still who urged the library to hold the event: not because they necessarily endorsed the views of the speakers, but on intellectual freedom grounds.

Notably, such advocacy was nowhere to be found on any professional librarian platforms. For example, after awarding SPL the Gale/LJ Library of the Year Award for 2020, Library Journal decided it had to temper its initial enthusiasm with a correction and a Message to the Library Community, where it acknowledged that SPL had rented a meeting room to an “anti-trans organization” and wished “that the library had not allowed that event to go forward.” The only Office of Intellectual Freedom mention of the event I could find was a blog post from a contributor who supported SPL’s decision on intellectual freedom grounds. The comments mostly disagreed.

This is disappointing. For as much as community members who oppose the inclusion of Gender Queer or Drag Queen Story Hour need to accept that others have the right to access materials and programming with which they vehemently disagree, so too must those who would oppose the acquisition of Irreversible Damage or an event organized by the Women’s Liberation Front. As my HxLibraries colleagues Michael Dudley and John Wright have emphasized, libraries have a responsibility to facilitate encounters with difference. This is a long-standing function: as I previously wrote, this was one of the six assumptions of the Public Library Inquiry going back over 70 years ago. Facilitated encounters with difference are vital for the promotion of free expression and therefore intellectual freedom.

Defending the indefensible

Judging from numerous statements, resource guides, and events, defending the inclusion of “controversial” materials is more precisely a defense of materials controversial to conservatives. But we know progressives engage in censorship too: there is the example of WoLF at the Seattle Public Library for one, and in recent years, it is left progressives who have challenged books such as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or Of Mice and Men.

I can anticipate possible rebuttals here: “some challenges are more threatening than others, and some populations are more vulnerable than others. These aren’t equivalent scenarios.” They may deny it’s censorship, claiming “collections are overly homogeneous, we’re weeding to make room for better items,” or “no one is stopping someone from speaking, we just won’t give hate speech a platform.” Some will say, “Don’t try to ‘both sides’ this issue; you’re enabling fascists.” Or the worst-case scenarios get floated, such as “You think white nationalists should be able to reserve meeting rooms? Should climate change denial books be on the shelves? How about Holocaust denial?”

Maybe those are good points. Maybe on this Night of the Long Reads, you defend certain ideas while purging others in the name of justice, and there is no time for discussion. However, libraries must represent their communities in all their diversity, and that means collections will inevitably contain materials and programming that offend some patrons. Librarians are of course free to personally disagree with speech they find objectionable; at issue here is whether or not in a professional capacity librarians should solely promote access to the ideas they support and actively obstruct access to the ideas they oppose. Yet if we are committed to intellectual freedom, this requires us to oppose censorship in any form, including the censoring of hate speech.

Americans who think censorship of hate speech is an effective means of building a more just society may want to take a look at Europe, or otherwise consider how these efforts tend to backfire. And crucially, people benefit from having a structured forum for engaging with controversial ideas. Note that I have used terms such as “structured”, “facilitated”, and “curated” in this piece. Librarians have a unique opportunity and responsibility to provide access to controversial ideas as well as promote dialogue across differences in a thoughtful fashion. This is in sharp contrast to the Thunderdome-like atmosphere that pervades commercial mass media platforms.

We do not know why people read what they read or attend the programs they attend, and we should not presume to know. Would-be censors should check their inner authoritarian and re-read their Mill: one’s own certainty is not the same as absolute certainty. Is Mill too passé for your liking? My HxLibraries colleague Sarah Hartman-Caverly has explained in this Substack and elsewhere how a posture of certainty suppresses rather than enables free expression. And no less an authority than Nadine Strossen and Emily Knox have argued that broad freedom of speech is what allows social justice movements to organize, and it is marginalized people who are punished most severely when free speech is curtailed.

I am not suggesting libraries must passively accept all materials and meeting rooms requests. This is why selection criteria are in place and events policies exist. The argument is that libraries must not make determinations about the inclusion of controversial ideas based on viewpoint alone.

On the Road, again

So, back to the drawing of the young woman reading Kerouac: I would now like to thank the man who mused that not many young women read Kerouac, because it gave me an idea. What more powerful demonstration of intellectual freedom than a visual pairing of unlikely readers encountering forbidden books? How about an “I READ BANNED BOOKS” poster of Abigail Shrier reading Gender Queer, or Maia Kobabe reading Irreversible Damage? Now that’s making a (principled) statement!

As professionals and individuals we should oppose censorship and promote dialogue, especially around controversial topics. We should all have curated and spontaneous opportunities to encounter ideas that challenge us, that provoke us, that confound us, that surprise us. Any of us has the capacity to be the seeker of information or the censor — who do you imagine yourself to be?

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer- or editorially-reviewed, all posts must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, send an email with the article title, author name, and article document to hxlibsstack@gmail.com. Unless otherwise requested, the commenting feature will be on. Thank you for joining the conversation!

References and further reading

Alexandra Alter and Elizabeth A. Harris, “Attempts to Ban Books Are Accelerating and Becoming More Divisive,” New York Times, September 16, 2022.

American Library Association, “The American Library Association Opposes Widespread Efforts to Censor Books in U.S. Schools and Libraries,” November 29, 2021.

American Library Association, “Banned and/or Challenged Books from the Radcliffe Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of the 20th Century,” 2005.

American Library Association, “Labeling Systems: An Interpretation of the Library Bill of Rights,” June 30, 2015.

Freddie deBoer, “You Can't Censor Away Extremism (or Any Other Problem),” March 11, 2021.

Michael Dudley and John Wright, “Speaker Controversies, Library Spaces and the ‘Right to the City’,” Heterodoxy in the Stacks, September 7, 2022.

Sarah Hartman-Caverly, “Long Tail Metaphysics: The Epistemic Crisis and Intellectual Freedom,” IFLA Journal vol. 48, no. 3 (2022): 373-82.

Sarah Hartman-Caverly, “The Wailing and Gnashing of Tweets,” Heterodoxy in the Stacks, October 28, 2022.

Katie Herzog, “Controversial Feminist Event at the Library Goes on Despite Threats, Interruptions, and Protests,” The Stranger, February 4, 2020.

Marisa Iati, “Booksellers Association Apologizes for ‘Violent’ Distribution of ‘Anti-Trans’ Title,” Washington Post, July 16, 2021.

Illinois Library Association, “Intellectual Freedom in an Age of Political Polarization: A Conversation with Nadine Strossen and Emily Knox,” April 12, 2021.

James LaRue and Eleanor Diaz, “50 Years of Intellectual Freedom,” American Libraries, November 1, 2017.

John Stuart Mill (of his own free will), On Liberty (London, 1859; Project Gutenberg, Jan 10, 2011), Chapter 2.

Lisa Peet and Meredith Schwartz, “Correction: The Seattle Public Library Listens Up | Gale/LJ Library of the Year 2020,” Library Journal, June 3, 2020.

Victoria Rahbar, “Gender Queer Most Challenged of 2021,” Intellectual Freedom Blog, April 4, 2022.

Meredith Schwartz, “A Message to the Library Community,” Library Journal, June 10, 2020.

Ross Sempek, “Meeting Rooms and Sacred Spaces Cause Schisms in Seattle,” Intellectual Freedom Blog, January 30, 2020.

Nadine Strossen and Greg Lukianoff, “Hate Speech Laws Backfire,” Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, September 30, 2021.

Eugene Volokh, “Seattle Public Library Reaffirms Rights of Trans-Skeptical Feminist Group (and Everyone Else),” Reason, January 10, 2020.

Excellent piece that delivers chills at its conclusion!

#shamlessplug HxLibraries is so honored and excited to welcome Dr. Emily Knox as our spring symposium keynote speaker -- save the date of Thurs. 2/23 4pm eastern.

I read Kerouac when I was in high school!

We never know why someone is reading a book-- whether they are "hate reading" it or reading it because they expect to love it. And of course, reading the book could change their mind.

An example of a progressive "book banning"--https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2020-11-12/burbank-unified-challenges-books-including-to-kill-a-mockingbird