Smoke/Screens

A Tale of Two Vices

I.

Generationally speaking, I am something of a straddler. Born in 1979, I have been lumped in with the youngest end of Generation X and the eldest end of the Millennials. My cohort and I have been labeled the X-ennials (sounds like a plant) and the XYers (vaguely reminiscent of Robert Bly). Leaving aside for now the extent to which these labels reflect useful sociological categories as opposed to reifying neoliberal market imperatives, I will say that I do have the feeling of having witnessed an old world give way to a new one from my childhood to adulthood. This is not intended as some profound statement, nor is such a sentiment exclusive to my own generational experience. With those caveats out of the way, I would like to elaborate on two seemingly unrelated developments.

The first is perhaps the most obvious for a Substack about libraries and librarianship: the dramatic shift of information provision from print to digital. When I started high school in August of 1993, it was still standard for students to turn in essays written on loose leaf paper. By the time I graduated in June 1997, increased access to computer terminals and printers had altered these requirements. I was in middle school when I used an OPAC for the first time at the North Raleigh branch of the Wake County Public Library: orange text on a black screen. Card catalogs remained, but like so many others I found the OPAC far more efficient. There wasn’t an abundance of terminals, and I remember having to stand in line and wait my turn. Once I had access to the World Wide Web, I whiled away many hours perusing lyrics databases for my favorite bands; in this period before search engines, I would discover new sites through webrings.

The proliferation of digital platforms is not just a matter of how information is accessed, but how people communicate with one another. I acquired my first email address in the fall of 1997 as a college freshman, and I acquired my first mobile phone in 2003. Until relatively recently, all manner of notifications were transmitted on paper, both business and personal. I relished opening the mailbox as a kid, only to be disappointed with how much mail was for my parents. “You’re not missing out on anything,” my mother assured me, more than a hint of resignation in her voice, “it’s all bills.” I remember long distance phone calls as a precious and carefully premeditated affair, owing to the considerable expense. How expensive were they? I was allotted ten minutes once per month to call my best friend in New York on a Sunday night. I never experienced caller ID until I got a cell phone, so whoever was on the line was always a surprise. And, if you shared a landline, the identity of the person who would answer the phone was just as much an uncertainty for the caller. I delighted in making absurd answering machine messages, which were not meant to be informative so much as entertaining. I mean, come on: why would I use an answering machine message for a banal recitation of my name and number when I could play a snippet of a Kids in the Hall sketch about answering machine messages? In the early days of wider cell phone usage, text messaging was often an a la carte service that could be charged per message. Thus, the cell phone was still primarily a phone. It was not yet a smartphone, the adoption of which vastly accelerated changes in interpersonal communication.

Do I even need to enumerate the ways that modes of human communication have changed? Probably not, but I will anyway. Talking seems to be one of the last things many of us use our phones for, particularly Millennials and Gen Z, who apparently suffer from phone anxiety. It’s largely intermediated and slightly delayed communication (i.e., text and email) in addition to many other functions. Thirty years ago if you wanted to take a picture, use a calculator, or look up the capital of a global city, you had to use a separate dedicated technology for each of those tasks. It is easy to see that our phones do so much for us, and I readily concede this. You may very well be reading this on your phone!

Though even as our phones do so much for us, our chronic consumption seems to do something to us as well. Reduced attention span appears to be an epidemic. Many adults struggle mightily with untethering their phones. The extent to which our youngest become attached to phones is the subject of many alarming claims about the connection between screen time and adverse behavioral outcomes. And I haven’t even addressed the horrifying environmental and human rights issues associated with cell phone production. Smartphones can be lifesaving and life ruining, quite literally.

II.

The second social change I have witnessed is the decline of cigarette smoking in the United States. And get this: when I was growing up in the 1980s, my parents told me there was far less smoking around compared to when they were younger. But compared to now, during my childhood, cigarettes seemed everywhere. I remember the dubious courtesy of non-smoking sections in restaurants, where you could still smell smoke, just a bit farther away. Some retail establishments kept the cigarettes out of reach, but in others you could easily get your hands on them to take them to the cashier for making your purchase. My large extended family included some heavy smokers, whose prodigious habits could be made into a Seuss-like rhyme: they smoked indoors, outdoors, in moving cars, and stopped cars; they smoked at first light, and at the end of the night. I am aware that this was not everyone’s experience, but for me, casual and frequent smoking seemed commonplace and unremarkable. It was an adult activity, like drinking coffee or using four-letter words. Even at my high school, where students certainly couldn’t get away with smoking in the bathrooms (as my mother could in the late 1960s), there was a tolerated smoking area called The Strip, a long stretch of privately-owned sidewalk adjacent to high school property. Most of the congregants were under 18, and if it caused concern, there was no obvious attempt to force the property owner to discourage the activity.

And when I went off to college: there were smoking dorms and non-smoking dorms. Smoking was tolerated, almost required, in the dance space at my undergraduate institution. When the musician Mirah performed one evening she requested that no one smoke during her set. I remember being perplexed by this. What’s the big deal? It’s just some hazy air! Once I was of age, I visited many smoky bars and clubs. And though smoking had already been banned on US domestic flights by the time I began flying, I flew in planes that retained the armrest ashtray.

As with the phones: do I need to detail how much smoking has changed? My children have never been around smoke inside of any building, or around smoke in immediate proximity to a building for that matter, since smoking is banned in parks, around schools, and within 15 feet of an entrance. They’ve never shared a car with a smoking passenger, and certainly have never seen anyone use a car lighter or an ashtray in the center console or the door. You know those videos where bewildered children are shown something like a rotary phone or a VHS tape and asked to explain what they are? My children could identify a rotary phone or a VHS tape, but they probably couldn’t identify an ashtray. Admittedly, this says as much about how the wider world has changed as much as it does about my changed social status.

We owe many of these changes to aggressive public health campaigns operating on multiple fronts. Non-smokers and allied agencies have strenuously lobbied for the necessity of smoke-free environments, and the rights of non-smokers to be free from smoke. Smoking cessation programs are available through health departments and insurance providers. And just try to light up a cigarette on the scant plot of land where it is still allowed. It won’t be indoors anywhere, or on public property, or any form of mass transit. You won’t find an ashtray built into your new car.

Anti-smoking campaigns have often included an emphasis on children, for two main reasons: the vulnerability of growing bodies to smoking’s ill effects, and the belief that it is easier to never become a smoker in the first place than to break the habit later. This is sound reasoning and I don’t dispute it. However, I recall reading a book in the early 2000s that argued the youth-focused approach was insufficient. The book claimed that campaigns that focus on children can send an unintended message: that choosing to smoke as an adult is permissible or less of a concern. The most effective anti-smoking campaigns have been holistic in their emphasis on the dangers of smoking by anyone, not just minors. (Or so the authors claimed. I tried in vain to identify this citation in preparation for writing this essay, but I could not track it down. It was a slim volume, and I have a vivid memory of reading it when I lived on Charles Street in Baltimore, so this would have been 2004 or 2005. I recall a specific focus on anti-smoking messaging in the Clinton years. In case anyone wants to get involved in solving a monographical mystery!)

III.

I think about this point – the holistic approach versus the youth-specific one – when it comes to campaigns to curtail screen time and promote responsible use of social media. It seems almost daily there are alarming reports of the deleterious effects of social media on minors. Social media use, we are told, is a likely driver of a youth mental health crisis. Parents are encouraged to restrict screen time and otherwise monitor usage.

Adolescents tend to be naturally suspicious of their elders. So I wonder: how seriously can kids take adult admonitions to put their phones down when everywhere they look, adults are consumed by their phones. We’re at the park with our kids, head down, absorbed in our screens. We’re at the breakfast or dinner table absentmindedly scrolling. We’re picking up our phones by our bedside first thing in the morning and it’s the last object we touch at night. My grandfather, who smoked right up until he died from mouth cancer and emphysema, used to say you know you’re addicted to cigarettes when the first thing you do in the morning is reach for that pack.

Am I saying that adults should never zone out on their phones in front of children? That I am not guilty of doing so? No and no. I am not trying to shame anyone, and certainly not the exhausted and overstimulated parents who just need to turn off their brains for a few minutes. I also don’t want to insult my audience, all of whom are reading this thanks to a series of tubes.

I also recognize that my analogy of “phone addiction = smoking addiction” does not quite hold. Smartphones and similar devices have drawbacks, but we tend to see the positives as outweighing the negatives. Not to mention, we have been increasingly compelled to use handheld devices to navigate everyday transactions. The cigarette, on the other hand, possesses a singularly insurmountable negative quality. Smoking has not been wholly eradicated either: conventional cigarette smoking has declined, but electronic cigarettes usage is going up.

My point is this: campaigns to dissuade children from engaging in harmful behavior when they can very well see adults doing that same thing are bound to fall short. Adolescents especially have a refined bullshit detector, and threatening directives to moderate screen time while the grown-ups around them stare hollowed eyed at the very same apps they’re told are bad for their self-esteem will seem a lot like “do as I say and not as I do.”

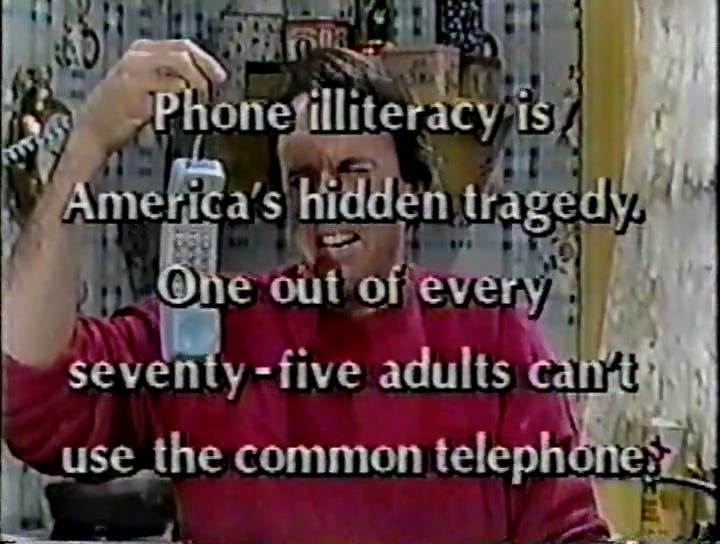

Of course, some will argue that so much alarmism about personal device usage is just that: alarmism. They might point out, rightly so, that all new communication technologies have incited some degree of panic upon introduction, until they are absorbed into everyday life: the book, the telephone, or the television. And surely, I do not mean to make a deterministic argument, that it is the smartphone itself that makes us do anything. Yet, how something is designed and regulated can shape its usage, and much like cigarettes don’t smoke themselves, just because something requires human agency to be used does not mean that thing isn’t powerful. Public health awareness campaigns and individual initiative are all well and good, but eventually policy interventions are required to make a real difference. Casual and frequent smoking was enabled and encouraged — until it wasn’t.

Fear-based messaging and “Just Say No!” aren’t the kind of policy intervention I’m talking about. Telling children and adults to moderate smartphone usage is a weak solution for stemming compulsive behavior. Public tolerance of smoking changed because people not only made changes at the individual but at the institutional level as well, and because the tobacco industry was significantly weakened.

Fear-based messaging is also insufficient because it fails to address the why of a problem. People are addicted to their phones for a reason. I wonder if it is simply a matter of compulsive habit, or if there is some deeper need being satisfied. I wonder what we can give ourselves instead. I wonder how, amidst an increasingly fractured political landscape, we recenter meaningful human connection both online and offline. Importantly, for HxLibraries: I wonder how LIS educators and public librarians can more strongly emphasize the benefits of deep reading. To not just promote access, but stress the importance of a focused and consistent reading practice. And I wonder what larger scale interventions are possible.

Maybe one day you will visit a restaurant, and you and your party will be asked if you prefer to sit in the scrolling or non-scrolling section. Maybe free digital detox programs will be promoted as part of massive public health campaigns. Granted, for some this might sound like a totalitarian nightmare. At the very least, I hope my children will one day recall their mother scrolling and swiping on her phone, and it will seem a strange behavioral artifact of the past. “It seemed like grown-ups were always staring at their phones,” they might say “or at least, a lot more compared to now.”

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer- or editorially-reviewed, all posts must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, send an email with the article title, author name, and article document to hxlibsstack@gmail.com. Unless otherwise requested, the commenting feature will be on. Thank you for joining the conversation!

References and Further Reading

Jennifer Abbasi, “Surgeon General Sounds the Alarm on Social Media Use and Youth Mental Health Crisis,” Journal of the American Medical Association, 330 (1), June 14, 2023.

American Lung Association, “Tobacco Control Milestones,” last updated January 19, 2023.

Katie Brigham, “How Conflict Minerals Make It Into Our Phones,” CNBC, February 15, 2023.

John Buschman, “Talkin’ ‘Bout My (Neoliberal) Generation: Three Theses,” Progressive Librarian 29 (Summer 2007): 28-40.

Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute, “History.”

Jon Haidt and Zach Rausch, “Kids Who Get Smartphones Earlier Become Adults With Worse Mental Health,” After Babel, May 15, 2023.

Johann Hari, Stolen Focus: Why You Can’t Pay Attention – And How to Think Deeply Again, New York: Crown, 2022.

Jennifer Ibrahim and Stanton Glantz, “The Rise and Fall of Tobacco Control Media Campaigns, 1967-2006,” American Journal of Public Health 97(8), August 2007: 1383-96.

Kristen Jones and Gary Salzman, “The Vaping Epidemic in Adolescents,” Missouri Medicine 117(1), January-February 2020: 56-58.

The Kids in the Hall, “Answering Machine,” S4E10, original airdate February 2, 1994.

Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking About Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Cornelia Pechmann and Ellen Reibling, “Antismoking Advertisements for Youths: An Independent Evaluation of Health, Counter-Industry, and Industry Approaches,” American Journal of Public Health 96(5), May 2006: 906-13.

Catherine Price, How to Break Up with Your Phone: The 30-Day Plan to Take Back Your Life, Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2018.

Elissa Sanci, “Everything You Need to Break Up With Your Phone, From Free Tricks to Phone Safes,” New York Times, March 3, 2023.

U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “How to Quit Smoking,” last updated March 6, 2023.

U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, “The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General,” Atlanta: U.S. Public Health Service, 2006.

Jen Wasserstein, “My Life Without a Smartphone is Getting Harder and Harder,” The Guardian, November 4, 2021.

“What Ever Happened to Webrings?” Hover, May 14, 2021.

Vicki White et al, “Do Adult Focused Anti-Smoking Campaigns Have an Impact on Adolescents? The Case of the Australian National Tobacco Campaign,” Tobacco Control 12, 2003: ii23-ii29.

Maryanne Wolf, Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in the Digital World, New York: Harper, 2018.

Amina Zafar, “Social Media Gets Teens Hooked While Feeding Aggression and Impulsivity, and Researchers Think They Know Why,” CBC, November 16, 2023.

Like many others, the first thing I do when I get up is get online (although on my laptop, not a phone, and now often it is the second thing as I have a bird feeder and sometimes spy on the birds first).

I was born in 1963 and graduated from library school the year before the Web launched, so I've been contemplating writing something very much like this!