I. One

I recently viewed the 1998 movie You’ve Got Mail for the first time. I am not quite sure why I missed this when it first came out, other than I would have been 19 years old and therefore probably too busy watching something much more sophisticated like Paul Schrader’s Affliction, which was released at the same time. It wasn’t that I was too cool for rom-coms – even then, two of my favorite films were Annie Hall and Moonstruck. In fact, Playing by Heart came out the same month as You’ve Got Mail, and I saw that in the theater. But Playing by Heart had Gillian Anderson, Ellen Burstyn, Gena Rowlands, and Sean Connery! All I knew about You’ve Got Mail was…Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan. I have enjoyed some of their movies, but I wouldn’t say they’ve ever been an automatic draw for me.

Thus did the last 25 years go by without my ever having seen this movie that apparently made $250.8M at the box office. And I probably would have been content to let more of my life go by in this fashion, except someone whom I admire very much let it be known this is one of her favorite movies. Intrigued, I made a point of checking out a copy from the library. Let’s just say I did it for heterodoxy. Perhaps many of us are inclined to think of living “the HxA way” as only applying to matters of serious intellectual import, but the principle of charity can certainly be applied to more low-stakes endeavors, such as agreeing to watch a loved one’s favorite movie that you previously sneered at. I am older (not sure about wiser) and more willing to check my biases. So, on a recent Saturday night I watched You’ve Got Mail.

I was encouraged by the opening credits. As I already indicated, Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan – ho hum. But Parker Posey? Check. Jean Stapleton? Outstanding. Dave Chappelle? Steve Zahn? Dabney Coleman? Yes, yes, and yes. And it should go without saying that Nora Ephron at the helm constitutes a major endorsement. But I think what really allowed me to be receptive for whatever would occur over the next two hours was hearing Harry Nilsson’s “The Puppy Song” play over the credits. It is an irrefutable fact that Harry Nilsson was one of the greatest songwriters of the twentieth century. Okay, fine: I can’t cite any research to back this up, but I would argue it is self-evident. Hearing Harry clinched it for me. I could feel my skepticism dissolving and I started to think, maybe I could like this movie.

II. The Point!

By now, you might be wondering if you are reading a straightforward review of a film from 25 years ago. For additional context: You’ve Got Mail opened the same year that Larry and Sergey founded Google, Congress passed the Copyright Term Extension Act, and Bill Clinton became the second US President to be impeached. You might be asking yourself “is this not a Substack about libraries and librarianship?” Yes, this is Heterodoxy in the Stacks, and I promise there is a related point!

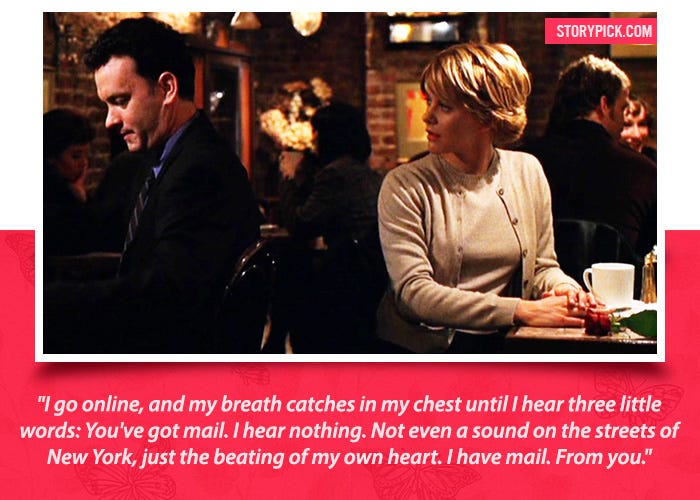

Before I arrive at that point, I think it is important to provide a brief summary of the film. For the unfamiliar (as I was until recently), You’ve Got Mail concerns a woman named Kathleen (Meg Ryan) and a man named Joe (Tom Hanks) who live in New York City. They are America Online account holders who strike up an anonymous yet frequent email correspondence after meeting in a chatroom. Their modern epistolary exchanges become more intimate over time, with both feeling closer to one another than they do with their real-life significant others. But wait! There is a catch: Kathleen and Joe do know one another in real life, they just don’t know it. Not only do they know each other: they are business rivals who are inclined to hold the other in contempt. Students of classic film might find the plot similar to the 1940 film The Shop Around the Corner. This is no mistake, as You’ve Got Mail is based on this earlier film, albeit with a modern twist. Personally, I found myself drawing more immediate parallels to Desk Set (hey, look – I made a somewhat library-related point!). Now that the contours of the plot have been sketched, it is time to get to the actual point.

One trepidation I had going into You’ve Got Mail was that it would feel dated, to a distracting degree. Nothing says mid to late 90s quite like an AOL logo and a dial-up sound. But as the events of the film unfolded, I was able to put those features out of mind. They were dated, but no more distracting than watching someone use a landline or a Rolodex or other such primitive technologies in a film set in the late twentieth century. No, what stretched my credulity watching a 1998 film from the vantage point of 2023 was the unquestioned primacy of print media.

Let us start with the character of Frank, played by Greg Kinnear. Frank is Kathleen’s boyfriend, and a respected and influential left-leaning newspaper columnist. He uses his columns to champion causes he deems urgent, doing so with what we are to understand is his trademark incisive wit. We see Frank lauded for his moving prose and sharp analysis. That a newspaper columnist could be influential is not, of course, news (this was a key element of the television series Sex and the City, which also debuted in 1998 and took place in Manhattan). What struck me in this movie was the way in which this case was visually made. We see people brandishing physical copies of the newspaper, reverently reading Frank’s columns aloud as though they were the Liturgy of the Word. America may have been online in 1998, but here in this moment, the Internet is purely social. No one in the rarefied Manhattan bubble has any inkling of the seismic changes coming to newspaper consumption. Paper is king and Frank the columnist is its esteemed courtier. He recoils in the face of new digital technologies, defiantly procuring a manual typewriter.

However, Frank is but a supporting character in this story, as is his newspaper column. The main event are Kathleen and Joe, who occupy another paper-based trade: the bookstore. Kathleen is the David in this tale who runs a small, beloved independent children’s bookstore while Joe is the scion of a chain bookstore that mercilessly eradicates the competition. Though really, as Joe coldly points out to Kathleen, her small, independent bookstore is not his competition. In fact, Joe doesn’t appear to have any real competition. His family’s colossal bookstore chain is at the apex of the bookselling industry. He is confident that the only obstacle to his business’ expansion is other bookstores.

Yet by 1998, Amazon had already been in the online bookselling business for three years, and it was in 1998 that Amazon began selling music and movies. If anyone in Joe’s orbit is concerned that e-commerce poses a threat to the physical bookseller, he doesn’t show it. In a moment of dramatic irony, the viewer in 2023 will know that he is on the cusp of a dramatic shift in the physical publishing landscape, yet all he can see is limitless expansion. The interiors of Joe’s chain bookstore are as massive, shiny, and sleek as any modern office building. With its high ceilings, tasteful white trim, and wide staircases, the space could be for a hospital or an accounting firm as easily as it could be for books. It evokes unassailable permanence.

To consider this film in the HxA way, let us be charitable to Kathleen and Joe. Surely Kathleen cannot be blamed for seeing the most immediate threat to her livelihood as being the much bigger bookseller. It is possible that if the chain bookstore had not popped up so suddenly, she would have spent more of 1998 forecasting e-commerce trends in the publishing industry. But what about Joe? He tells us he is a businessman. He knows the book business. How could he have been caught unawares? Though maybe Joe cannot be faulted here either. After all, the paperless society as predicted by F.W. Lancaster in 1978 had not materialized by the end of the twentieth century.

Moreover, the light and casual ways in which Joe and Kathleen use and understand the Internet are much in line with the initially rosy predictions for how the World Wide Web would transform global society for the better. In 2023, we are all too familiar with the downsides of the Internet with respect to governance, content, and provision. But in the 1990s the Internet was heralded by many as a force for good that would democratize global communications. Information would be free, and therefore so would the people. (Not everyone believed that, but the Cassandras were naturally ignored).

By 1998 this dream had become pure fantasy, though such a trajectory was not inevitable. In his dissertation-turned-book Profit Over Privacy, Matthew Crain compellingly describes the battles waged over US Internet policy in the 1990s. The issue at the center of these battles was two-fold: would the Internet be for public good or private profit, and how would these interests be served in policy terms? Depending on how you look at it, you might believe the Internet does operate in the public interest, due to the abundance of free content and the relative ubiquity of access. But a more critical appraisal would maintain that ad-driven, privacy-deficient information provision is not free, and comes at a very high price. We routinely and often unavoidably offer our personal data in exchange for access. Where that data goes, and whether or not it works for or against our personal and collective interests, are frustratingly difficult questions to answer, for most Americans anyway.

III. Remember

But back to You’ve Got Mail and the bookstore. This film was not meant to be a political economic treatise on nascent Internet policy under Bill Clinton. It is, to be clear, a lighthearted romantic comedy. Yet from my perch in 2023, one cannot help noticing the romance in this picture is more than what transpires between Kathleen and Joe. You’ve Got Mail now functions as a nostalgia vehicle for a time when print was the undisputed medium for meaningful communications, and email was a delightful novelty. It also routinely evokes the timeless romance between a reader and his or her cherished book. Finally, I am not the first to point out the dissonance between the fantasy version of the Internet vs. reality in You’ve Got Mail, nor am I the first to interrogate the political economic dimensions therein.

Nearly a quarter of the way through the twenty-first century, we have yet to arrive at Lancaster’s paperless society. I suppose “considerably less paper-based communication” is more of a mouthful. Meanwhile, libraries have continued providing access to physical collections in physical spaces, and so much more. The struggles of bookstores, chain and independent alike, have been well-documented, while libraries remain largely beloved, present controversies aside. So while the booksellers in You’ve Got Mail seem entirely ignorant of the Internet as a powerful means of large-scale information organization and access, some libraries had already been online for decades.

Many of us in the world of libraries are familiar with charges of irrelevance. We have been told librarians and library leaders need to innovate. We hear that libraries need to operate more like businesses. The thing is, I would argue it’s the other way around. Organizations might be slow to innovate and adapt, and a library is no exception. All groups can be stymied by inertia, fear of the new and unusual, or simply not knowing what they don’t know. But generally speaking, libraries have been on the forefront of innovation in information provision, while industry has often had to play catch-up. Libraries are not perfect, but they remain excellent examples of how to structure information provision in the public interest.

I know, I know: there’s an obvious weakness in my analogy. Library networks differ in significant ways from Internet infrastructure. So while libraries may be good examples, they are not necessarily models. For that, we would be better served by looking at postal networks, the other great love of my life (besides, of course, libraries). Though perhaps that’s for another essay.

It has been 25 years since You’ve Got Mail imagined the Internet as a means of facilitating intimate and profound human connection. What will online information provision look like in another 25 years? Can Internet infrastructure be reorganized as a public good? Call me a hopeless romantic, but a girl (and an Internet user) can dream.

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer- or editorially-reviewed, all posts must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, send an email with the article title, author name, and article document to hxlibsstack@gmail.com. Unless otherwise requested, the commenting feature will be on. Thank you for joining the conversation!

References and Further Reading

Reed Albergotti, “He Predicted the Dark Side of the Internet 30 Years Ago. Why Did No One Listen?” Washington Post, August 12, 2021.

Box Office Mojo, “You’ve Got Mail,” nd.

Clinton White House, “The National Information Infrastructure: Agenda for Action,” September 15, 1993.

Matthew Crain, Profit Over Privacy: How Surveillance Advertising Conquered the Internet, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021.

Woodrow Hartzog and Neil Richards, “Why Europe’s GDPR Magic Will Never Work in the US,” Wired UK, February 20, 2020.

Amanda Hess, “‘You’ve Got Mail’ Is Secretly a Tragedy, Too,” New York Times, December 19, 2018.

Ron Klain, “Inequality and the Internet,” Democracy no. 37, Summer 2015.

F.W. Lancaster, Toward Paperless Information Systems, New York: Academic Press, 1978.

Harry Nilsson, “Jump Into the Fire,” RCA Victor, 1972.

Olivia Rutigliano, “Was You’ve Got Mail Trying to Warn Us About the Internet? (Or Telling Us to Give Up?),” Literary Hub, May 20, 2022.

Keenan Salla, “The Evolution of the Online Public Access Catalog,” Sutori, nd.

Alina Selyukh, “How Barnes & Noble Turned a Page, Expanding for the First Time in Years,” NPR, March 7, 2023.

Dan Schiller, “Reconstructing Public Utility Networks: A Program for Action,” International Journal of Communication 14 (2020): 4,989-5,000.

Arthur P. Young, “Aftermath of a Prediction: F.W. Lancaster and the Paperless Society,” Library Trends 56, no. 4 (Spring 2008): 843-58.

I still haven't seen this one (although I did watch the documentary you recommended related to Viv Albertine). I was just thinking about the internet yesterday and how it has gone from a space where communication felt open and free to a space of increasing top-down control.

So good!