Forging a Path Between Illiberalisms: Towards Dialogical Librarianship

How city planning theory can help the liberal practitioner navigate between ideological excesses across the political spectrum.

[Image: Traveller_40 (flickr) CC BY-NC-ND 2.0]

Introduction

As some readers may recall, prior to becoming an academic librarian, I worked for 11 years in the field of urban policy analysis, and, as such, city planning is a disciplinary perspective I have often been able to draw upon in my theorizing about librarianship.

One of my all-time favourite planning theory texts is Dialogical Planning in a Fragmented Society by Thomas Harper and Stanley L. Stein: it’s a fascinating and richly theoretical overview of the philosophical basis for liberal professional interventions in complex multicultural societies. Even non-planners of a philosophical bent seeking a better foundation for understanding liberalism in postmodern times will find much in the book to reward their attention; and, as it’s aimed at understanding the foundations of a profession concerned with furthering the public interest, I would argue that many of the authors’ insights are well-suited to applications in librarianship, especially in our current moment of political and social fragmentation. In particular, I believe it can assist in articulating some “first principles” for heterodox librarianship that can help us navigate between two polarizing streams of illiberalism on both the Left and the Right.

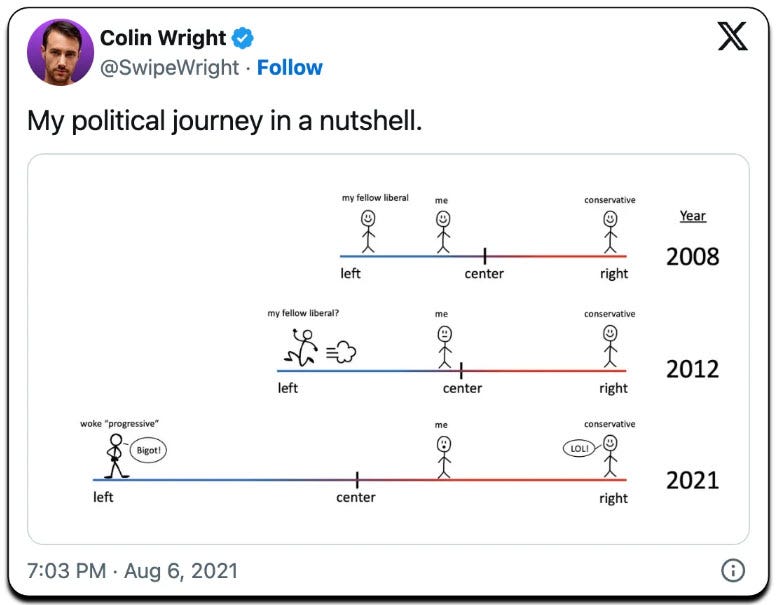

Situating oneself between these extremes has become of urgent concern for many. Recall biologist Colin Wright’s viral cartoon depicting his political journey: a stick person in 2008 existing happily at left-of-center with his “fellow liberal”. However, in 2012 the latter figure runs off so far to the left that by 2021 the presumed “center” has shifted considerably, leaving the Wright figure seemingly allied with the political Right, while his former “fellow liberal” calls him a bigot.

As Bill Maher has also routinely opined, “I didn’t leave the Left, the Left left me.”

This turns out to be a long-standing phenomenon, as David Oppenheimer recounts in his book Exit Right: The People Who Left the Left and Reshaped the American Century, wherein the political Left has engaged in (as he puts it) “a clear pattern [of] shaming and cancelling. The puritanical moralism. The persistent influence of Marx. The metastasizing of noble goals of liberation and equality into destructively utopian theories of human nature and society.” As a result, many old-school liberals like myself have expended a great deal of thought and energy over the past better part of a decade trying to understand the nature of this shift and the impacts it has had on our society, primarily our liberal public institutions—like libraries.

In 2025, however, a new calculus is emerging for those on the center-Left: how to understand and situate oneself as a liberal when the illiberalisms of the Left which were, only a few months ago, so ubiquitous and influential are being harshly suppressed and eradicated from the public realm in a markedly illiberal fashion by a populist Right administration led by President Donald Trump, which is targeting for elimination anything that can be labelled (legitimately or not) as “DEI”—the multipronged war against Harvard University being perhaps the most blatant.

Tearing up the Constitution of Knowledge

To some observers, this campaign has the hallmarks of a war on knowledge itself: David Ignatius, writing at The Washington Post, warns that Trump’s massive cuts to scientific research, data and information, and higher education in general “is a tragic mistake. Its destructive effects could last for a generation.” Yascha Mounk, while conceding that “the current assault on higher education is, in large part, of the universities’ own making”, and that the Trump administration could have pursued other more reasonably liberal interventions, argues that Trump’s Assault on Harvard is an Astonishing Act of National Self-Sabotage. Adam Serwer in The Atlantic further worries that these sweeping assaults portend a New Dark Age, writing,

The book burnings of the past had physical limitations; after all, only the books themselves could be destroyed. The Trumpist attack on knowledge, by contrast, threatens not just accumulated knowledge, but also the ability to collect such knowledge in the future. Any pursuit of forbidden ideas, after all, might foster political opposition…This purge will dramatically impair the ability to solve problems, prevent disease, design policy, inform the public, and make technological advancements. Like the catastrophic loss of knowledge in Western Europe that followed the fall of Rome, it is a self-inflicted calamity.

Taken together, Trump appears to be targeting every element of what Jonathan Rauch refers to as the “constitution of knowledge”: government (via the indiscriminate cuts to government agencies); the legal system (ignoring Supreme Court rulings and intimidating law firms, leading the American Bar Association to file a lawsuit against the administration); journalism (threatening to sue journalists who cite anonymous sources or calling for them to be fired); and the academy (slashing funding through the National Institutes of Health by 43% and barring from funding any projects utilizing any one of dozens of terms which might be characterized as “woke”, but many others which are entirely neutral, legitimate and essential for many forms of scientific inquiry including “woman” “female” and “mental health”). Then of course there was Trump’s dismissal of the Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden which went essentially unexplained, and his March 2025 executive order dismantling the Institute of Museum and Library Services, which the General Accounting Office (GAO) ruled in June to be in violation of Federal law, as the President cannot unilaterally withhold funds already approved and distributed by Congress.

All this has led some liberal figures formerly focused on addressing the corrosive effects of institutionalized wokeness to question the extent to which their own efforts might have inadvertently contributed to enabling these illiberal executive actions.

Anti-woke Critics Left and Right, and the Need for Principles

In a recent interview for Heterodox Academy, Steven Pinker was asked by Alice Dreger if there was some hazard that critics of DEI and wokeness in the academy might end up bearing some responsibility for Trump’s assaults on Harvard’s independence. Pinker replied (at 31:50),

I don't know if it'd be responsible because you don't want to, like, not criticize them because then the Trump administration could run away with the criticisms and kind of appropriate them.

Interestingly, Glenn Loury asked the same question of John McWorter (at 2:08):

GL: I'm just saying DEI is on the ropes “DEI bad, get rid of DEI.” The question I have for you is whether or not you and I have any responsibility in our sustained attack on the people with three names [leading anti-racist authors Ta-Nehisi Coates, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Ibram X. Kendi] and our contempt for the overemphasis on racial identity factors and you've given voice to it in describing how you think that some of in the humanities have overplayed that card...do we have blood on our hands metaphorically speaking for having abetted this revolution?...Do we have any responsibility for that?

JM: No, that kind of question implies that we shouldn't have said anything or that we should have only mumbled in an academic way which would have had no effect. Something needed to be done because we live in a real world of real people. The backlash was going to be too extreme at first and maybe could be trimmed...I fully understand that social history is going to be messy but our hearts were in the right place and silence would have been inappropriate.

For many liberal opponents of the identitarian excesses of the Left has also come a (perhaps uncomfortable) realization that engaging in such criticism has often involved reference to—and alliances—with those on the political Right. Yet, as Marxist scholar Vivek Chibber argues in his interview How the Left Got Lost: (1:08) this has been of necessity, because

the people on the Right are saying something correct and, you know, if the sky is blue and my enemy says the sky is blue I'm not going to tell them it's red to disagree with them, that's just a true thing…If the only people criticizing the way in which identity politics is being played out today, the only people doing it, is the Right, you hand over all of these critiques to them and people are going to go to the Right…they're going to say "If I value free speech therefore I'm a conservative." We're at the point where if you value free speech you say, you're a conservative.

Chibber’s observation really resonated with me personally: I reviewed my YouTube subscriptions recently for the first time in years and discovered, to my (small-l) liberal surprise, that nearly 2/3 of them were for Right-leaning podcasts, sources or personalities which I’d found compelling in terms of their arguments on many of these matters. And I’ve made some great conservative friends and colleagues over the past five years, some of whom are associated with either or both Heterodox Libraries and the Association of Library Professionals. However—and at the risk of dismaying some of these friends and colleagues—my liberal willingness to entertain conservative views and perspectives cannot extend to approving of Trump’s indiscriminate attacks on all these democratic institutions.

Steven Pinker, in the same Heterodox Academic interview quoted above, also acknowledges the tendency for liberals to seek Right-leaning content and allies, but warns

I think it is it is a real phenomenon that people who start out as critics of DEI, political correctness, wokeness, social justice warriors and so on, there's a danger of not only enabling…MAGA extremism but actually joining MAGA. And I have seen a number of people who are so burned by having been canceled or threatened or frustrated, that instead of carving out a defensible philosophy of academic freedom and free inquiry they say, “Those are my enemies, they're also the enemies of MAGA so I'm going to join MAGA, I'll have a lot of comrades there, and the woke social justice warriors are just so odious and despicable that the more they're punished the better.” I think that's a mistake because it leads to a kind intellectual nihilism, but it also means that the restraints on academic freedom are going to be way worse because as bad as DEI is, they're not the government...

Pinker argues that what is essential is to be able to articulate what we believe in, rather than just reacting against what we oppose. If not, the risk is that, as journalist Cathy Young argues at The Bulwark, one would focus only on the illiberalism and irrationalism on the political Left, while ignoring extremism on the populist-nationalist Right. Helen Pluckrose concurs, pointing out that many conservative voices that criticized the illiberal Left now overlook or downplay illiberalism on the Right (25:50):

there's a complete loss of nuance and therefore when we witness authoritarian actions on supposedly your side people turn a blind eye and this has been happening very much since Trump has taken office and that people are now who are calling out previously authoritarian behaviors and now are now turning a blind eye or even supporting them...this is what I'm trying to urge people to do at the moment is to maintain consistent principles.

Like Pinker, she calls on critics to instead believe in and adhere to first principles. In light of these observations and cautions—and with a view to enhancing professional and nonpartisan neutrality—I would like to turn now to Harper and Stein’s Dialogical Planning in a Fragmented Society to see if there may be guidance on locating these principles.

Dialogical Planning Principles for Heterodox Librarianship

For Harper and Stein, planning is inherently normative in positing a free, equal and autonomous—but situated—individual as the basic unit of a liberal society, but adopts a pragmatic approach that eschews utopian visions, and seeks incremental and dialogic pathways to decision-making and conflict resolution in the public interest (xix)—very much like how I’ve positioned the neutral library on this Substack. To fulfil this normative stance, they argue that planning should be critically liberal, procedurally liberal, pragmatic, communicative, and incremental. What I’d like to do now is briefly summarize these principles with a view to their relevance for librarianship in politically fragmented times.

Critically Liberal

First to clarify: Critical liberalism should not be confused with critical theory (which posits some normative ideal and then criticizes some aspect of society for failing to meet that ideal) or critical social justice (which reduces all human interactions as occurring between oppressors and the oppressed [see Pluckrose & Lindsay]). Our starting point is that liberalism should be understood as multifaceted, with political, economic, epistemic and cultural dimensions which, as Emily Chamlee-Wright points out, limit the powers of governments, encourage innovation, inspire and permit open inquiry, and encourage tolerance of others.

Instead, Harper and Stein explain how critical liberalism tempers the metaphysical view of the autonomous individual held by classical liberalism by recognizing that individuals in pluralist societies exist in the contexts of communities, which may not be able to afford that individual full access to necessary resources. This justifies the need for positive interventions to empower some stakeholders—a perfect example being the retrofitting of the built environment to accommodate persons with disabilities, or targeted outreach efforts in partnership with relevant stakeholders to lower barriers to access to some of their members.

Because critical liberalism contextualizes people as situated individuals in terms of circumstance (i.e., socio-economic class and geographic contexts), rather than essentializing them according to immutable group identities, or rendering all social relations to a Foucauldian exercise of power, it is a pathway to a form of commonsense DEI in library workplaces that would address some of the criticisms often leveled against such initiatives. This is why I would argue DEI regimes should be reformed to be critically liberal, rather than be shut down altogether, as is being done under the Trump administration.

Procedurally Liberal

This is a principle I’ve written about elsewhere on this Substack: the stance proposed by John Rawls in his book Political Liberalism in which governments or institutions don’t impose “comprehensive doctrines” or belief systems on society, but instead restrict themselves to maintaining those liberal processes on which all can agree and which are the necessary foundation for democratic engagement: freedom of thought, freedom of speech, intellectual freedom, and equality before the law. A similar way of expressing this idea is “constitutional patriotism”, a concept coined by a pupil of Hannah Arendt’s named Dolf Sternberger. According to Jan-Werner Müller and Kim Lane Scheppele, constitutional patriotism is

the idea that political attachment ought to center on the norms, the values, and, more indirectly, the procedures of a liberal democratic constitution. Thus, political allegiance is owed, primarily, neither to a national culture, as proponents of liberal nationalism have claimed, nor to “the worldwide community of human beings”…Constitutional patriotism promises a form of solidarity distinct from both nationalism and cosmopolitanism.

Constitutional patriotism would address directly the postliberal view of conservatism that—contrary to the liberal view of the autonomous individual—holds that individuals are defined by loyalty to families and tribes. Drew Perkins believes it no longer makes sense to characterize the political tensions in America as existing between the Left and the Right, but to instead on the extent to which actors across the spectrum distinguish between liberty and authoritarianism. This, again, should be a determination based on a pragmatic assessment of the known (or likely) impacts of political actors.

However—and this has important implications for libraries and librarians—the civic virtues of constitutional patriotism must be taught by and embedded within a society’s institutions, as Roger Partridge argues, through “story, education, ritual, and shared public life.” He adds:

The price of admission to a liberal democracy should be respect for the rules that make peaceful coexistence possible. That includes rejecting efforts—from any quarter—to impose religious orthodoxy, racial essentialism, or ideological loyalty tests. Liberal societies need to rediscover the confidence to say not only what they stand for, but what they will not tolerate: forced conformity, political violence, and illiberal creeds that reject mutual respect. Clearer legal boundaries may be needed. But if governments, civil society leaders, and educators are willing to name liberal values explicitly and to defend them without apology, this moral clarity may be enough.

A focus on mutually-agreed upon rules for coexistence over ideology should, ideally, discourage political tribalism (and the presumption of owed loyalties it entails), and allow for professionals to be more willing to engage in criticisms of authorities and institutions for violating those rules, rather than deflecting or ignoring such breaches out of a sense of political partisanship. Procedural liberalism would thus (theoretically) make “criticizing one’s own side” a conventional practice on both the Left and the Right, and not contrary to presumed political loyalties.

Pragmatic

A pragmatic approach to professional practice means focusing on what works, rather than on specific ideologies or beliefs. The rationale for this approach, as William James put it in his classic 1906 lecture “Pragmatism’s Conception of Truth,” is that truth should have (metaphorically speaking) “cash value” in the real world—in other words, it should make a practical difference what one believes:

Pragmatism...asks its usual question. “Grant an idea or belief to be true,” it says, “what concrete difference will its being true make in anyone's actual life? How will the truth be realized? What experiences will be different from those which would obtain if the belief were false? What, in short, is the truth's cash-value in experiential terms?” The moment pragmatism asks this question, it sees the answer: true ideas are those that we can assimilate, validate, corroborate and verify. False ideas are those that we cannot.

An orientation to pragmatism would better enable librarians to avoid treating ideologies or unfalsifiable concepts as uncontested fact. A prime example in this regard would be the notion of implicit (or unconscious) bias, which has been heavily institutionalized in librarianship and a staple of the LIS literature, yet according to social psychologist Lee Jussim in recent years the field of psychology has seen “a great walking back of many of the most dramatic claims made on the basis of the [Implicit Association Test] and about implicit social cognition more generally.” Indeed, there is a growing body of scholarly literature critical of its underlying assumptions, the methods used to assess it, and the appropriateness of applying it to workplaces. A 2020 comprehensive review in the journal Personality and Social Psychology Review determined the concept to be so untenable that the article’s authors Olivier Corneille and Mandy Hütter “recommend[ed] discontinuing the usage of the ‘implicit’ terminology in attitude research and any research inspired by it” (p. 224, italics added).

One might from a pragmatic perspective also question the Jamesian “cash-value” of Trump’s slogan “Make America Great Again” which has long been criticized for seeming to presume that America isn’t currently great; evokes a mythical past in which it was great but without specifying exactly when and in what way; and the actual means by which this new greatness is to be accomplished. In other words, as a political slogan it is undeniably brilliant and galvanizing, but its value as a basis for actual public policy is highly questionable.

A pragmatic orientation geared towards determining which ideas do, in fact, have positive outcomes for the real world would also then encourage open debate rather than conformity to a presumed orthodoxy on either the Left or the Right. Debate is, in turn, central to planning’s communicative function.

Communicative

Harper and Stein follow other planning theorists such as John Forester, Patsy Healey and Judith Innes in positioning planning not as a top-down imposition of the planner’s vision but instead of democratically opening up the planning process to all stakeholders through processes of communicative action, which are characterized by mutual learning, mediation and consensus-building (p. 144). This communicative mode of planning translates quite naturally to librarianship and the model proposed by John Wright and myself of multidimensional library neutrality, wherein the librarian acts in a mediating capacity regarding matters of public debate by collecting resources representing multiple perspectives irrespective of the librarian’s own values, and making public spaces available to speakers and groups championing those views, thereby informing the democratic process and allowing users and communities the autonomy to debate such matters in good faith.

This communicative, collaborative, and deliberative planning ethic is quite at odds with the manner with which the Trump administration both fired the Librarian of Congress without reasonable cause and sought to shutter the Institute for Museums and Libraries without accounting for the diverse functions it fulfills, including funding interlibrary loans and tribal libraries. It also stands apart from the view articulated in R. David Lankes’ Atlas of the New Librarianship which is openly interventionist, exhorting librarians to take the lead on “improv[ing] society through action” (p. 118), and “chang[ing] the community and society for the better” which would require librarians to learn how “to plot and scheme, cajole and convince. How to map power and gain power to put behind a vision,” which is why he believes that “library school should be [] a caldron and training ground for activists and radicals” (p. 180). The problem with Lankes’ proposal is that most activists and radicals have a very particular belief about the desirable pace of social change.

Incremental

Dialogical, consensus-seeking processes in communicative planning are core to the planner’s role in mediating gradual and consensual social change. As Harper and Stein argue, “[t]he only possible justification for planning in a postmodern society is an incremental one. The alternative paths to change—coercion and conversion—are not legitimate” (p. 145). This ethos stands in stark contrast to both the gleeful chainsaw-wielding stylings of the Trump administration and much of the literature in radical librarianship: Eino Sierpe, in his 2019 article, “Confronting Librarianship and its Function in the Structure of White Supremacy and the Ethno State” forcefully rejects incrementalism—and librarianship itself—as being structurally indistinguishable from white supremacy, in his words, “a deliberate construct for racial subjugation” (p. 90). Lankes’ call to activism similarly seeks to have librarians lead on rapid social change in their communities; and how else can we understand the Project 2025-inspired agenda of the second Trump administration but as one dedicated to swift and radical social, cultural, and political changes?

Clearly these are completely incompatible worldviews: one sees rapidly-forced change as unjust, while the other demands it. How to resolve this tension?

Conclusion: Preserving Chesterton’s Fence with Planning Theory

In his 1929 book, The Thing: Why I Am a Catholic, G.K. Chesterton wrote,

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

In other words, in your zeal to change the world, be careful about what you tear down, for it may be fulfilling a very essential function of which you are unaware and the world will be the worse off without it. Conservatives have understood this principle very well, which is why so many critics on the Right have (in my view) justifiably expressed alarm at the ambitions of the progressive Left and their enthusiasm for “disrupting and dismantling” society’s institutions in the pursuit of their particular vision of social justice. It is all the more dismaying, then, that the Trumpists have been tearing down fences wherever they find them, with a particularly troubling consequences for those institutions at the heart of the “constitution of knowledge.” What Rauch stresses in his book is that The Constitution of Knowledge only functions when those players in various parts of its institutions are committed to truth, factuality, correction, etc. Accordingly, we can't isolate libraries from the effects of upstream or lateral destruction being wreaked upon other epistemic institutions.

While the present opposing projects to tear down liberal institutions may be expressed similarly, there are profound differences between the illiberalisms described above: as we’ve seen, the progressive (far) Left has a long history of seeking to punish and/or exclude those who oppose its utopian visions for perfecting humanity and improving society in the future, while the Right seeks revenge on the Left for attempting to do just that, while being driven by a tribalist and revanchist impulse to reclaim—and impose—an imagined ideal past.

By contrast, the view from the liberal center is that it would be a mistake to “disrupt and dismantle” our institutions, regardless of political imperative. This is why I believe our profession requires an infusion of external principles to help it navigate between these competing illberalisms, and that the Dialogical Planning model of Thomas Harper and Stanley Stein provides just the guidance required. By articulating a librarianship that is critically liberal, procedurally liberal, pragmatic, communicative, and incremental, the Dialogic model has the potential to help us avoid the excesses at both extremes of the political spectrum, and the freedom to criticize both.

References

Corneille, O., & Hütter, M. (2020). Implicit? What do you mean? A comprehensive review of the delusive implicitness construct in attitude research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 24(3), 212-232.

Lankes, R. D. (2011). The atlas of new librarianship. The MIT Press.

Müller, J. W., & Scheppele, K. L. (2008). Constitutional patriotism: an introduction. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 6(1), 67-71.

Pluckrose, H., & Lindsay, J. A. (2020). Cynical theories : how activist scholarship made everything about race, gender, and identity-and why this harms everybody (First edition). Pitchstone Publishing.

Sierpe, E. (2019). Confronting librarianship and its function in the structure of white supremacy and the ethno state. Journal of Radical Librarianship, 5, 84-102.

Good to see Rauch's "Constitution of Knowledge" foregrounded in this article. Rauch's work on epistemic institutions and the checks and balances among them is more important than ever in a time when many institutions (like universities) need to do internal reforms rather than fundamentally change their missions under assaults on them and their core purposes of scholarship, teaching, and service.

I just returned from a very lively and timely Heterodox Academy conference--lots of ideas to process from the event.

I will note, to extend some of the thinking in Michael's article, that Nadine Strossen, former President of the ACLU, and now FIRE Board member, and one of our best scholars and experts on free speech, introduced a panel of university presidents who debated (sometimes fiercely) what options are available when colleges and universities are targeted by the Trump administration. In introducing that panel, Strossen described our current predicament (and I'm roughly paraphrasing her), as one where we lived with the "soft despotism" within our colleges and universities, and other cultural institutions, with the prevailing monoculture, cancel culture, and likely Title IX violations, which has now being overtaken by a "hard despotism" of the current administration, with violations of civil liberties and due process , assaults on epistemic institutions' funding, threats against international students, coercion of law firms, and coercion of media organizations. Certainly there's been authoritarian measures, and two forms of illiberalism, at work in our institutions and government for a number of years. The question at this point is how to move forward (if it's possible) with the current administration going to a place of fundamental violations of liberal democratic norms and principles.

Very thoughtful article Michael, and very well-reasoned. Thank you for reminding us of liberal principles in a time of epistemic confusion and chaos.