Epistemic Vice (and Virtue) in the Shakespeare Authorship Debate

The suppression of the authorship controversy is a case study in academic cancel culture: a self-reinforcing belief system of dogmatism, groupthink, and foreclosed inquiry.

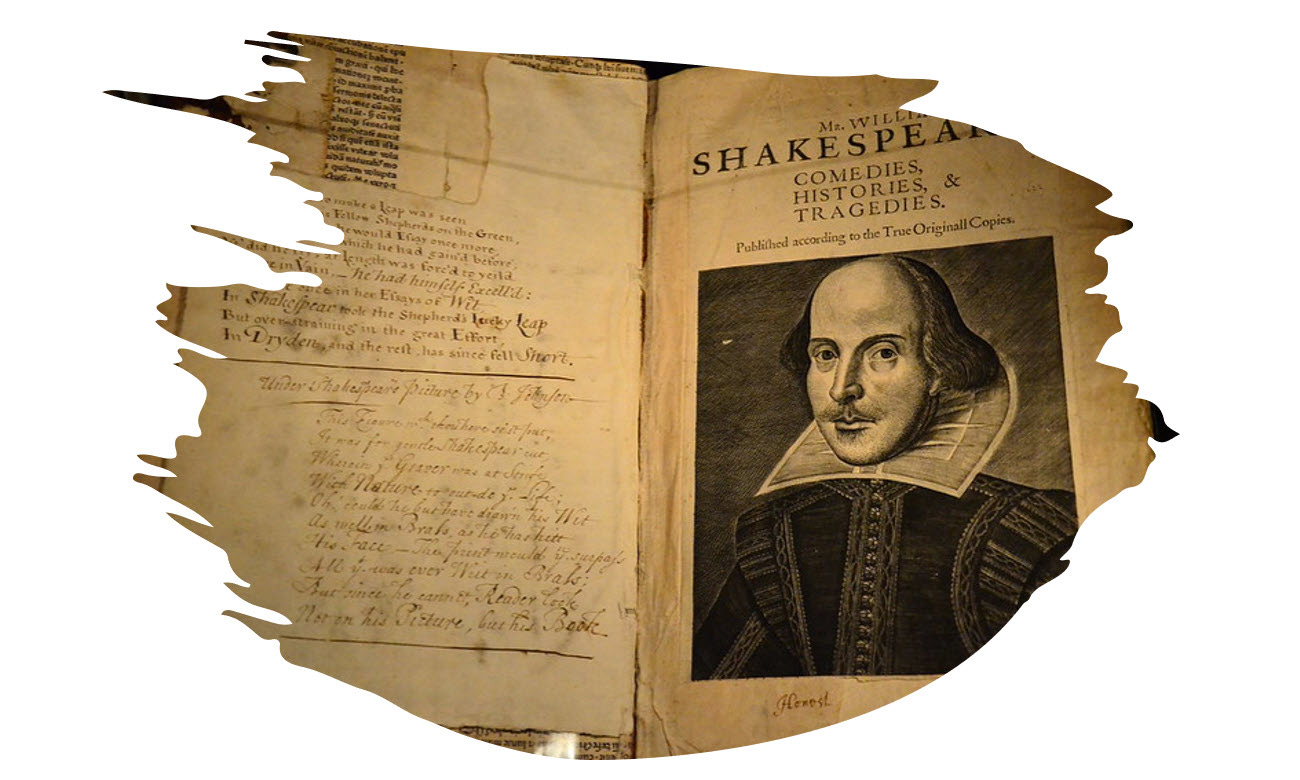

Image: “Pages of William Shakespeare's first folio at the Bodlean Library, Oxford.” Ben Sutherland [flickr]. Cropped in PowerPoint. License: CC 2.0)

(This is a slightly edited version of my presentation to the Heterodox Libraries Spring Symposium, Curiosity, Controversy, and Intellectual Courage, May 23rd, 2024).

This post is not, strictly speaking, about who Shakespeare was or wasn’t. Instead, based on my 2023 book The Shakespeare Authorship Question and Philosophy: Knowledge, Rhetoric, Identity, it uses theories of epistemic vice and virtue to focus not on the truth-indicativeness of the evidence for the authorial theories in the Shakespeare debate (i.e., their credibility), but rather on the truth-conduciveness of the belief- and knowledge-formation practices associated with those theories—in other words, the extent to which such practices tend to produce true beliefs rather than false ones.

Too often, what should, all other things being equal, be considered a legitimate literary and historical controversy is instead treated as a deeply polarizing and politicized—even moral—matter: we hear from experts and the major media that the skepticism surrounding the authorship of the Shakespeare works is a long-debunked and misleading conspiracy theory akin to flat-earth beliefs or moon-landing-denial or even Holocaust denial, one that smacks of elitism advanced by snobs and which no serious expert would support—but that, in any event, “who cares who wrote the plays and poems?” These types of rhetorical tactics demonstrate that the barriers to the academy facing the authorship question have very little to do with its inherent evidentiary merits, but to broader cultural and institutional factors that dominate belief-formation and knowledge construction concerning Shakespeare.

In light of curious mismatch between the scant positive evidence for the traditional authorial candidate, and the vitriol directed at anyone who raises doubts about it, the proposition I pursue in my book is that

The institutional and cultural resistance to doubt about the authorship of the works known as Shakespeare’s is rooted in ideologically-motivated truth claims arrived at through unreliable belief-formation and knowledge-generation practices and reinforced through a specific suite of rhetorical strategies and modes of public persuasion.

What the accusations levelled against doubters amount to are charges of epistemic vice, meaning poor epistemic conduct (i.e., deliberately ignoring evidence; acting in bad faith towards other knowers) and character (such as arrogance and dogmatism, or being closed-minded. However, when one’s charge of epistemic vice is based on motivated reasoning or other non-epistemic justifications that, in itself, is an act of epistemic vice.

Since the most common epistemic vice charge in this case is that skeptics are promoting a “conspiracy theory,” it is important that we examine this category from an epistemological perspective. According to Ginna Husting and Martin Orr in their 2007 article “Dangerous Machinery: Conspiracy Theory as a Transpersonal Strategy of Exclusion”, the labelling of any social or political critique as being “just a conspiracy theory” is a “pre-emption of the scholarly and investigation process” because the intended purpose of the charge is to call the speaker’s character into question, while mischaracterizing their claims and equating them with other, totally unrelated or clearly absurd claims.

Husting and Orr further criticize political scientists and journalists for unquestioningly assuming the internal validity of the term “conspiracy theorist” and limiting their inquiries into asking why such people hold the beliefs they do, rather than addressing the substance of their claims, which are thus delegitimized—it is in their words a “mechanism of exclusion.”

As such, Shakespeare skepticism may be dismissed and ignored, or cited only to be rebutted. Any gaps in the evidence for—and our understandings of—Shakespeare may be explained away by documents being lost to history, Shakespeare’s so-called “lost years”, or else a metaphysical belief in the “miracle” of natural genius and imagination, as illustrated here in this quasi-religious 1799 engraving, the Infant Shakespeare Attended by Nature and the Passions.

(Image: Public Domain)

I argue that the consensus view is not just a single belief, but a system of belief:

1) A propositional belief (p) William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon was the author William Shakespeare;

2) a second-order belief about that belief—that p is a certainty, beyond doubt and beyond questioning;

3) a host of varying explanatory beliefs (i.e., the fallacy of special pleading) each premised on faith and justifying p (e.g., the “lost years”; the “miracle of genius”; key documentary evidence being “now lost”);

4) a reflexive belief that believers in p—themselves—are authoritative and as such cannot be questioned about p;

5) an ethical belief that questioning p is not just factually incorrect but immoral; and

6) a juridical belief that those who question p may justifiably be isolated, excluded and marginalized by institutions of scholarship.

My argument is that it is the mutually-reinforcing nature of all these beliefs— rather than just the contents of the consensus attribution itself—that contributes to the resistance on the part of Stratfordian believers to examining honestly the evidence at hand. Swap out the particulars and I would suggest that this becomes a template for understanding other examples in our politics of dogmatism, groupthink, polarization and conflict—popularly known as cancel culture.

This system of belief has caused the Shakespeare academy to fall prey to what sociologist Ilana Redstone refers as The Certainty Trap: the three fallacies of believing that a given question is settled such that all should agree on it; that anyone who does disagree must have ulterior, bad-faith motives; and that, if only dissenters had access to the same information as the believers then there would be no point of disagreement. These fallacies are compounded by an imperative to suppress any discussion of the authorship question, thereby short-circuiting those very liberal institutions we rely upon to mediate disputes: the academy, journalism, scholarly publishing and libraries.

In my book, I apply a number of external disinterested criteria and frameworks to this phenomenon, among them the six frames of Association of College and Research Libraries Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education, which is a normative dispositional way of understanding, practising, and teaching sound, ethically robust scholarship. What I conclude is that the rhetoric and scholarly practices common to the Stratfordian side of this debate are inconsistent and incompatible with those principles as outlined in the Framework.

This is why I believe that the authorship debate is not just a scholarly disagreement, but represents something larger: a “meta-problem” in the form of multiple levels of institutional failure in which our universities, schools and mass media have all willingly participated in foreclosing inquiry into a matter of foundational civilizational importance, thereby perpetuating one of the most tragic misallocations of intellectual energy in the history of knowledge.

There is another way: inquiry premised on epistemic norms and virtues such as open – mindedness, intellectual humility and an honest desire to seek the truth, no matter how ideologically inconvenient it may prove to be to oneself or one’s epistemic community. This necessitates recognizing and regarding with skepticism rhetoric emphasizing ethos (presumed authority) over logos (or reason), and instead insisting that claims on all sides of this—or any other—debate adhere to epistemic norms. As Jonathan Rauch argues in his 2021 book The Constitution of Knowledge, all knowers must be seen as fallible, and nobody has the final word owing to their authority – all claims must be open to scrutiny by third parties. These epistemological ethics and practices are more characteristic of the Oxfordian side of this debate: the academics and independent researchers advancing through evidence and argumentation the theory that the plays and poems were written by Edward de Vere, the 17th Earl of Oxford.

Instead of engaging in epistemic vice and condemning authorship skeptics and barring them from participating in the scholarly conversation, the Shakespeare academy needs to welcome them as fellow Shakespeareans, joined together in their shared passion for the plays and poems and a desire to pass their love to the next generation. The Shakespeare professoriate needs to grant academic freedom equally to doubters and to themselves, instead of fatally circumscribing their own investigations and those of their colleagues and students. Only then can the study of the life and work of this magnificent, brilliant and timeless Author become a fruitful and resilient field of inquiry, filled with wonder and possibility.

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer- or editorially-reviewed, all posts must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, send an email with the article title, author name, and article document to hxlibsstack@gmail.com. Unless otherwise requested, the commenting feature will be on. Thank you for joining the conversation!

Michael, thank you for this excellent article and also for the presentation about it you gave at the HxLibraries Symposium last Thursday. This is scholarship of the true "open inquiry" kind that we need more of. I have come to believe that academics become captured by "sacred narratives" in their disciplines, and sealed off from contrary evidence, as. much as people outside academia can become captured by conspiracy theories for their socially motivated reasons. The incentive structure in academia can be just as conformist, tribalistic, and focused on groupthink.

I'm reminded of Damrosch's "community of scholars" (We Scholars) and how it should operate to encourage debate and inquiry, and to encourage conversations outside of narrow specialities. Also, more recently, Kathleen Fitzpatrick's "Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach To Saving the University." The norms of scholarship and teaching have broken down too often into ideological conformity away from the best approaches to open inquiry. Those two thinkers point to a better way of reforming the academy so that it regains some credibility and trust. Your article is also a good example of how genuine "inclusion" is suppose to operate within a discipline or a community of scholars.

Also this meme made me laugh: https://x.com/SecretSunBlog/status/1790765164142223377/photo/1