Icons8 flat diploma 1.svg/Wikimedia Commons

Although the Master’s in Library and Information Science degree has been the subject of debate for years, the library profession’s recent emphasis on “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” has brought it under increased scrutiny. The library field is again asking whether it should be a requirement for a job as a librarian or whether the degree serves an unnecessary gatekeeping function, in addition to discussions over how the curriculum might be restructured.

Reflecting back on the public library systems in which I have worked makes me wonder if the focus on librarian positions is overly narrow, as I can recall many career paths in libraries that didn’t require the degree. In one large urban system the management team consisted of several degreed librarians— the Director, one of the Assistant Directors, and the heads of Cataloging, Collection Development, Branch Services, and Youth Services— but also several non-MLS employees, such as the heads of Facilities, Purchasing, Information Technology, Human Relations, and Marketing, as well as the second Assistant Director. The Head of Purchasing eventually became the Department Head over not just purchasing but also collection development and cataloging and from there moved into a higher-level position in another city department.

Given the increasingly diverse needs the public library system fills today, rather than abandoning the MLIS requirement for librarian positions, public libraries could continue to add more positions that don’t require it— social workers, system administrators, graphic designers, programmers, computer/ Makerspace instructors, and children’s performers come to mind, as do employees who could concentrate solely on creating programs for adults and youth. Marketing is another position that is needed more than ever, especially in this age of social media. In relation to DEI, this would bring in employees with a diverse range of skills and interests.

2016 09 UJ Meet Up Makerspace (c) Lukas Boxberger.jpg/ Wikimedia Commons

At the same time, for people with a desire to share their love of reading, or for subject matter specialists, or for those with a knack for classification or information architecture, or for people with a passion for archives and preservation, or for avid researchers, or for those with a commitment to intellectual freedom, the degree serves as a test of commitment to the field, provides students with the history and philosophy behind libraries, imparts best practices as well as the ethical grounding of the profession, and helps less well-connected graduates get a foot in the door (something that should merit consideration when it comes to DEI concerns). These are the types of people who are a very good fit for the world of libraries but who don’t generally have a lot of opportunities to share their talents outside of them, with bookstores offering historically low pay (and less of them in existence), the publishing industry offering a combination of high stress and low pay, and academia becoming an increasingly difficult career path. In a 2008 survey on the value of an MLIS, respondents mentioned “that the degree gave them the capacity to shape their interests and talents into a fulfilling career that they love and enjoy.” What will be the societal impact if these types of “interests and talents” become less valued, less developed, and less renumerated?

Closing of a landmark.jpg/ Wikimedia Commons

Although it could mean a reduction of librarian jobs overall during a period when there is a glut of jobseekers with MLIS degrees, it might be beneficial to let librarians concentrate on what they do best— develop and promote collections, perform in-depth research, catalog items, design information architecture, maintain archives— and let other tasks, such as computer assistance or housing navigation, fall to employees without an MLIS degree but with the corresponding interests and strengths. Despite the potential decrease in librarian positions, job satisfaction among librarians might well increase, while at the same time more positions would open up that don’t require the MLIS.

When I brought this up during a presentation on the future of the MLIS, I was told that we don’t want to create a “separate but equal” system, but that might be overestimating the appeal of librarianship. Perhaps non-librarians do occasionally feel like fish out of water, but I did not get the impression that those management team employees without the MLIS degree felt like they were “less than.” To the contrary, they seemed to thrive in the jobs they were doing and were probably relieved to have skipped out on the expense and time the MLIS degree requires. While they seemed to enjoy working in libraries, they were also able, if they so chose, to transfer their skills to other city departments and to the private sector with an ease that librarians can only envy.

When I was studying for my MLIS in the early nineties, there were some lightweight courses in the curriculum, which makes me think that the degree requirements could be shortened, or perhaps the MLIS could become a minor to a master’s (my preference) or bachelor’s degree in another subject. Some of those lighter courses, such as Developing Media Collections, are likely to have been replaced by more substantive “informatics” classes today; it would be interesting to hear from recent students as to how much “busywork” currently constitutes the MLIS education.

Metadata is a love note to the future (8071729256).jpg/ Wikimedia Commons

While there may be room for reconfiguration, if a library and information science educational requirement were to disappear entirely for librarian positions, there would likely be a decrease in pay and prestige for librarians, especially in an era when more and more research is being self-conducted online. Candidates without an MLIS might have an easier time getting a librarian position if the requirement disappeared, but the position could simultaneously become less desirable. As Geoff Shullenberger remarks in this episode of Outsider Theory on the topic of academia, “The person who gets elevated to the top of the field is like somebody who says oh this field is systematically and foundationaly racist and so it needs to be dismantled… there’s this kind of nice kind of symbiosis where a lot of these humanities fields the university doesn’t have much use for them anyway… the radicals who are being elevated are unwittingly doing the work of dismantling the fields and programs in which they are operating… and it’s all just part of this sort of death spiral of the whole system.”

Background on LIS Degree Requirements

Thank you to fellow Heterodoxy in the Stacks contributor Caroline Nappo for providing the following historical background to this piece.

The Master’s in Library and Information Science is a terminal, pre-professional degree. Unlike a research degree, in which a student prepares to conduct further research in a field, the pre-professional degree prepares the student to become a practitioner in that field. In this way, the MLIS is similar to a master’s in social work or education. The MLIS has many names, depending on how the degree is organized. It may be an MA or MS and may have a focus on library science, library and information science, information studies, or any number of permutations. It is a credential; while some states or areas of librarianship have formal certification or licensing requirements, there is generally speaking no legal mandate for librarians to possess a degree of any sort, let alone a master’s.

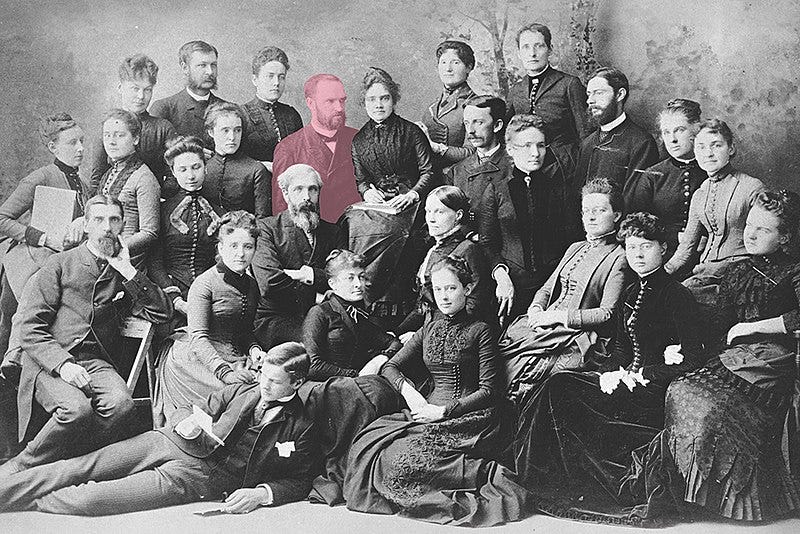

The start of library science as a field of study originates with Melvil Dewey and his founding of the School of Library Economy at Columbia University in New York in 1887. He moved the school to Albany because of Columbia’s admissions policies, which did not admit women at that time. From there, a variety of offerings in education for librarianship sprung up in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Some training programs were in higher education institutions while others were in libraries. Depending on the host institution, completing these programs earned you various credentials, ranging from a certificate, to a bachelor’s degree, to a bachelor’s degree plus certification (not a master’s degree, but a postgraduate certification).

1887-1888 class School of Library Economy at Columbia College.jpg/ Wikimedia Commons

Gradually, there was an effort to formalize library science as a research-based academic area, which included standardizing education requirements. In 1923, an economist named Charles Williamson was commissioned by the Carnegie Corporation to conduct a study on education for librarianship. He produced what is known colloquially as the “Williamson Report”, which determined that library training and education for librarianship were inconsistent and lacking in standardization. Echoing today’s debate, the report also stated that it was difficult to distinguish what makes someone a library professional versus a library worker. Williamson recommended that education for librarians become more cohesive and consistent, with some presiding authority overseeing the creation and implementation of these standards. Thus, the American Library Association began accrediting programs in 1925. One of the other immediate changes in education for librarianship was the phasing out of certificate programs, and the end of library-based training programs. Within a decade following the Williamson report, library science programs became exclusively academic, either awarding a bachelor’s degree or requiring one at minimum.

Another indicator that library science was remaking itself as a serious scholarly area occurred in 1929 when the University of Chicago opened the Graduate Library School. This was a research institution devoted to research problems in librarianship and was also the first doctoral degree program in library science. With the opening of the Graduate Library School, more programs opened at the graduate level for training and education in librarianship. By the mid-20th century the idea of the bachelor’s degree as the minimum requirement for working in libraries started to wane in favor of the master’s degree.

More and more master’s programs opened well into the 1970s, in anticipation of a great future need for library professionals. By the 1980s it became clear that this was a misjudgment, however, and a wave of closures began, including the prestigious marquee programs at Columbia and Chicago. A list of historically accredited programs can be viewed here: https://www.ala.org/educationcareers/accreditedprograms/directory/historicallist

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer- or editorially-reviewed, all posts must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, send an email with the article title, author name, and article document to hxlibsstack@gmail.com. Unless otherwise requested, the commenting feature will be on. Thank you for joining the conversation!

As for DEI. It's been a long, long time that LIS has worked on DEI issues. In the 1980s I worked with Margaret Myers of ALA OLPR on a project called "Each One Reach One" for minority recruitment. The larger institutions are asking for more and more DEI commitment but in LIS with the ethnic affiliates (I'm a life member of REFORMA) and SPECTRUM there is a history of commitment.

That does not seem to have altered the overall demographics much. When I visited many HBCUs to recruit I was unsuccessful because of low salaries in the field. I did a small study of 2018 grads and found that Asian and Hispanic graduation rates have increased, but not Black graduates. [(Yoon, JungWon and McCook, Kathleen de la Peña. 2021. “Diversity of LIS School Students: Trends Over the Past 30 Years.” Journal of Education for Library & Information Science 62 (2): 109–18.]

The recent revocation of academic status for librarians in the Texas A & M system is an interesting case:

"Nearly 30 librarians at Texas A&M University have lost either tenured or tenure-track status after the administration opted to reorganize the system’s 10 libraries. Administrators had previously asked librarians to move to a new department to keep tenure or relinquish it.

In all, 24 librarians moved to other academic departments, thus maintaining tenure, while 53 converted to staff status. Of those 53 librarians, 19 waived tenure and another nine gave up their tenure-track status, according to The Houston Chronicle."...administrators say the reorganization was designed to streamline and simplify library operations and emphasize student needs over librarians’ research, according to The Houston Chronicle.

https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2022/05/25/texas-am-librarians-lose-tenure-reorganization-plan

I don't know the inside details of this but it certainly throws open academic status in academic libraries.