For over a century, public libraries in the United States have advocated for federal support. The American Library Association first began discussing library expansion on a national level in 1919. In the early 1930s, ALA Executive Director Carl Milam drafted a National Plan for Libraries. These initial lobbying efforts culminated in 1937 with the creation of a library services division within the Office of Education, then part of the Department of the Interior. The American Library Association has maintained a policy office in Washington DC since 1945. Further landmark accomplishments have demonstrated that libraries are a national treasure, including the passage of the Library Services Act in 1956, the Library Services and Construction Act of 1964, the Library Services and Technology Act of 1996, and the creation of the Institute for Museum and Library Services in 1996.

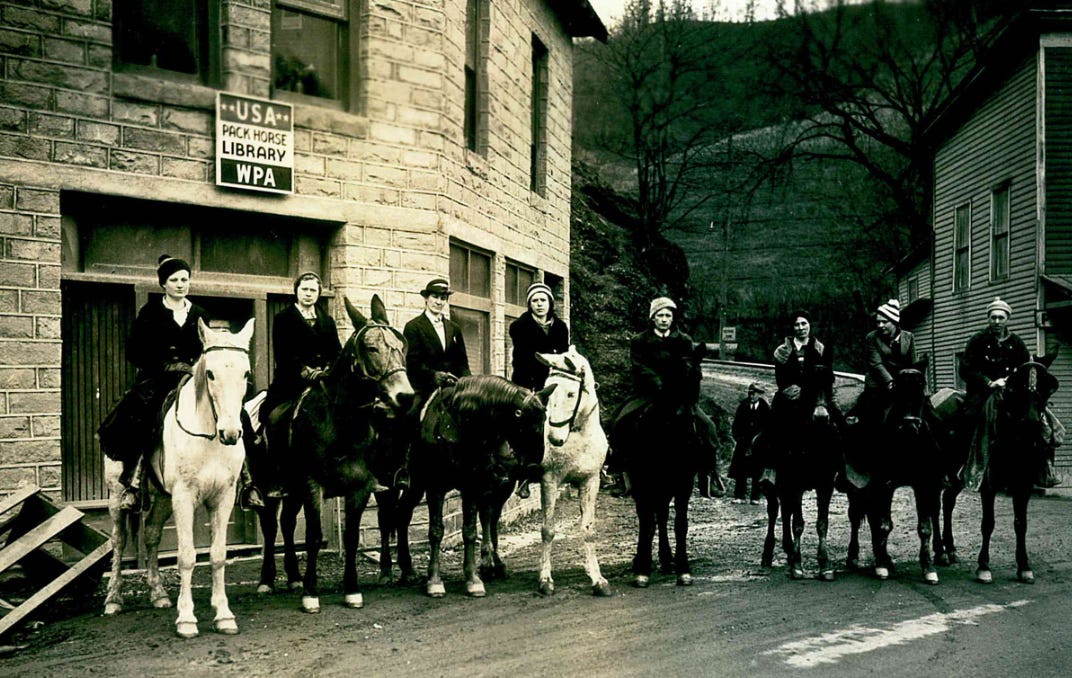

When the ALA and assorted library advocates first began vigorously lobbying for federal support in the 1930s, the world was coping with catastrophic economic conditions amidst a deep depression. The profound immiseration of this period cannot be overstated: at the Great Depression’s nadir in 1932-1933, unemployment in the United States reached a devastating 25 percent (for comparison: in November 2023, unemployment was 3.7%). Wages fell and banks collapsed. It might seem odd that this would be the decade for library leaders to make a plea for dedicated federal aid. But the rationale was compelling: since public libraries are community-supported, rural populations were at a disadvantage relative to their more population-dense counterparts. Moreover, the cascade of federal programs initiated under the Roosevelt administration convinced library supporters that this was a sensible approach. Library advocates repeatedly emphasized that 45 million Americans lacked access to library services by virtue of their geographic circumstances. They argued that to ensure equality of access to libraries, rural communities would necessarily require additional support to compensate for the more modest local tax base. Eventually this argument was extended to include any communities where assistance might be required to close gaps in access to services. The 1930s saw an explosion in library access: pack horse libraries, open air libraries, rooftop libraries. In the 2020s we have digital libraries, curbside delivery, and 24-hour libraries. Thus has the United States seen nearly one hundred years of steadily growing and guaranteed support for libraries, thanks to federal and state funding. As library historian Wayne Wiegand is fond of pointing out, there are more public libraries in the United States than there are McDonald’s restaurants.

It is undoubtedly a wonderful thing to ensure equality of access to library services. That every child and adult should enjoy similar opportunity regardless of their status or location is a democratic ideal and the embodiment of the American Dream. Public libraries occupy a crucial role in facilitating access to information for education, recreation, and self-improvement. And just as crucially, public libraries facilitate this access while remaining committed to intellectual freedom. Librarians are, ideally, trained to guide their patrons on how to access information and how to think about information – not what to access (outside of responding to a direct question) or what to think about it. To form one’s own opinion absent coercion is the right of every library user.

I was therefore of two minds when I learned Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts had introduced the Books Save Lives Act. Let’s start with what’s good about it: I love the title of the act, and one hundred percent agree with the sentiment. I also appreciate that Pressley wants to ensure that all school libraries have a trained librarian. However, the bill includes some requirements that would violate intellectual freedom and the very ethos of the public library as a locally embedded institution. I suggest that librarians and others committed to the First Amendment and intellectual freedom carefully evaluate Representative Pressley’s bill.

The Books Save Lives Act comes on the heels of state legislation in Illinois and California to combat book bans at the state level, as well as the Right to Read Act and the Fight Book Ban Act in Congress. 2023 has the ignominious distinction of being a banner year for book challenges in school and public libraries. The governors of Illinois and California have declared they’ve banned book bans, but there is no banning of book bans per se. Rather, in the Illinois case, all libraries receiving state funding would be required to adopt the American Library Association’s Library Bill of Rights or a similarly worded policy. Therefore, it would be more accurate to say that Illinois has heavily disincentivized item removal due to political pressure. There is no criminal penalty if an Illinois public library were to yank Gender Queer off the shelves without due process; but that library would risk losing its state funding. In California, school boards could face fines if they are found to have removed textbooks or school library books for discriminatory reasons. The California and Illinois approaches are similar to the enforcement mechanisms of the Children’s Internet Protection Act, which requires certain libraries to enable internet filters as a condition of their funding. Meanwhile, the Right to Read Act and the Fight Book Ban Act both seek increased support for school libraries.

The Books Save Lives Act takes a different approach in that it mandates inclusion of “a diverse collection of books” in school and public libraries. It does not mandate inclusion of specific viewpoints, but inclusion of authors who are from an “underrepresented community” or books about such a community.

Let us pause here. Acquiring books by a member of an underrepresented community or books about an underrepresented community (or a member of) sounds like a noble aim. Libraries should, through collections and programming, afford patrons the opportunity to open their minds to experiences and perspectives that they might not otherwise encounter. Any librarian involved in collection development should endeavor to acquire items that represent a broad and diverse range of ideas. There are always resource constraints – libraries cannot acquire everything – but it is well-established that librarians should aspire toward the building of diverse collections.

Yet I diverge with Representative Pressley’s proposed legislation, for two reasons. The first has to do with control. It seems unwise to enshrine collection development directives at the federal level. Not being a constitutional law scholar, I can’t say this violates the First Amendment, but at the very least it seems to be in opposition to the spirit of it. Librarians need the freedom to build collections without government mandates of what to include. Who wants to give the federal government the authority to stipulate what content belongs in library collections? This would be a dangerous precedent.

The second issue with Representative Pressley’s bill is the application of federal categories in the context of local libraries. An “underrepresented community” at the federal level does not always neatly translate to the local. Part of what makes public libraries great is the diversity of their local communities. Public libraries in the United States are a constellation of different demographics. Diversity is contextual at the local level, and library collections must be developed within that context.

Librarians should acquire books that showcase diversity of communities and authors, but legally compelling them to do so is not how to stem the current tsunami of book challenges. This is akin to the type of moralizing that libraries practiced from the late nineteenth century through the early twentieth century. Many librarians believed that because books were powerful, collection development should prioritize moral uplift. Similarly, there are those who would argue that contemporary librarians must diminish access to certain works in order to promote access to others that are deemed morally correct. The aim of Representative Pressley’s bill is understandable: she wants to protect access to books that might be especially vulnerable to challenges. But the way to ensure the inclusion of diverse books is not with a federal mandate. American librarians already have a professional one: the Library Bill of Rights, the second tenet of which states “Libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view on current and historical issues. Materials should not be proscribed or removed because of partisan or doctrinal disapproval.”

How then do we effectively confront book bans, if not with bills like that of Representative Pressley’s? As local institutions, libraries are comprised of and accountable to their community members. Libraries need both strong intellectual freedom policies and the means with which to facilitate thoughtful engagement with controversial viewpoints. What is controversial will vary within any given community. Librarians need to be equipped with the resources to champion viewpoint diversity, not to champion specific viewpoints. True, Representative Pressley’s bill does not mandate the inclusion of a specific viewpoint; it specifies books by or about underrepresented communities, which include ethnic and racial minorities, LGBTQIN (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and non-binary) people, religious minorities, and people with disabilities. There is no ideological specification, which means the viewpoints by or about underrepresented communities could represent diverse perspectives and experiences. Still, what is sorely needed is something this bill cannot provide: to ensure tolerance of controversial perspectives, as well as the epistemic humility required to do so.

Under the First Amendment and the Library Bill of Rights, we cannot prohibit access to controversial ideas merely because they are controversial. Likewise, we cannot and should not mandate access to specific ideas. We need all ideas – the good, the bad, the strange, the stupid – to determine those which are worth preserving. I am not making this argument from a place of ideological relativism. I do not think every idea has equal merit. What I do believe is that we can’t know which ideas have the greatest merit without discussion and contestation. As Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Schlott argue in their recent book, this is part of having a free speech culture. The reality is that people will always disagree, and on certain issues the disagreement will be vehement. The goal should not be to eradicate disagreement, but to find better ways to navigate it.

Speaking of discussion and contestation, it is perhaps worth noting that when the ALA first began lobbying for federal support, librarians were not in unanimous agreement. Some dissenters warned that bringing federal support into library services would curb libraries’ independence. Maybe these dissenters would argue that bills like Representative Pressley’s are the logical endpoint. But I am inclined to think state and federal allocations for library services are part of supporting libraries as a public good, which is a good thing. Libraries need federal support, not federal interference.

For those of us in the northern hemisphere, we have recently passed the winter solstice. Each day we get a little more light. We are all marking the start of a new year. I especially enjoy this holiday, since no matter who or where you are, we all observe the Gregorian calendar (though I think the French Republican calendar would have been a great standard, aesthetically speaking. Right now we could be in the month of Nivôse; how beautiful is that?!). As both a free speech enthusiast and, I suppose, an incurable optimist, I hope this new year brings us new opportunities to listen, to understand, and to thoughtfully disagree. And I am hopeful that public libraries can and should keep showing us the way.

To promote viewpoint diversity, Heterodoxy in the Stacks invites constructive dissent and disagreement in the form of guest posts. While articles published on Heterodoxy in the Stacks are not peer- or editorially-reviewed, all posts must model the HxA Way. Content is attributed to the individual contributor(s).

To submit an article for Heterodoxy in the Stacks, send an email with the article title, author name, and article document to hxlibsstack@gmail.com. Unless otherwise requested, the commenting feature will be on. Thank you for joining the conversation!

References and Further Reading

Andrew Albanese, “Congress Introduces New Bill to Fight Book Bans in Schools,” Publishers Weekly, December 6, 2023.

American Library Association, “The Children’s Internet Protection Act.”

⸻, “Library Bill of Rights,” adopted June 19, 1939.

Cheyanne Daniels, “Pressley Introduces Legislation to Fight Book Bans,” The Hill, December 14, 2023.

Jonathan Franklin, “New California Law Bars Schoolbook Bans Based on Racial and LGBTQ Topics,” NPR, September 26, 2023.

“Governor Pritzker Signs Bill Making Illinois First State in the Nation to Outlaw Book Bans,” June 12, 2023.

Greg Lukianoff and Rikki Schlott, The Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust and Threatens Us All — But There is a Solution, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2023.

A.J. McDougall, “Rep. Ayanna Pressley Introduces ‘Books Save Lives’ Act to Fight Bans,” The Daily Beast, December 14, 2023.

Eliza McGraw, “Horse-Riding Librarians Were the Great Depression’s Bookmobiles,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 21, 2017.

Kent Miller, “Libraries Stay Relevant For Old and Young,” Tallahassee Democrat, March 4, 2017.

Taiyler Mitchell, “Rep. Ayanna Pressley Wants to Take Down Book Bans With New Bill,” Huffington Post, December 14, 2023.

Lawrence Molumby, “ALA Washington Office: A Chronology of its First Fifty Years of Activities on Behalf of Libraries, Librarians, and Users of American Libraries,” May 1996.

R. Kathleen Molz, Federal Policy and Library Support, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1976.

Caroline Nappo, “Libraries and the System of Information Provision in the 1930s' United States: The Transformation of Technology, Access, and Policy,” PhD dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015.

Eric Novotny, “From Inferno to Freedom: Censorship in the Chicago Public Library, 1910-1936,” Library Trends 63, no. 1 (Summer 2014): 27-41.

PEN America, “Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley Hosts PEN America and Others for Roundtable on Book Bans,” December 15, 2023.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Current Population Survey,” accessed December 31, 2023.

U.S. Representative Ayanna Pressley, “Pressley Unveils Bill to Confront Rise in Book Bans, Ensure Inclusive Learning Environments,” December 14, 2023. '

⸻ “Books Save Lives Act,” one pager.

⸻ “Books Save Lives Act,” full text.

U.S. Senator Jack Reed, “As Some States Seek to Ban Library Books, Reed & Grijalva Reintroduce the Right to Read Act,” April 26, 2023.

This is a nice, aspirational message for the New Year!

In Brendan O'Neill's book "A Heretic's Manifesto", which is a collection of essays, the essay "Words Wound" reminds us that words do hurt, but censorship hurts us much more. "So yes, words can be painful. They can be used as weapons. You can feel 'ambushed, terrorised and wounded' by them. But that pain is incomparable to the pain of the physical ambush of the Charlie Hebdo offices, and the pain of the grief and sorrow those 10 deaths will have caused. Charlie Hebdo is accused of 'punching down'. That metaphor of violence - punching-should induce shame in everyone who uses it given the real, barbaric violence the Charlie Hebdo staff suffered for their blasphemies. The barbarism of censorship outweighs the pain of words, every time." - Brendan O'Neill, Words Wound, from A Heretic's Manifesto, page 167.